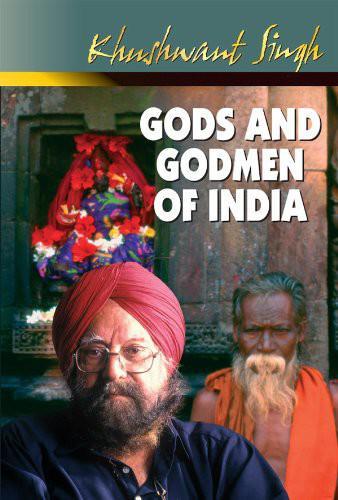

Gods and Godmen of India

GODS AND

GODMEN

OF INDIA

Khushwant Singh

Table of Contents

The Believer and the Agnostic: their Religion for Them, Our Doubts to Us

Religion without God, Prophets and Scriptures

In Search of a Home for their Knowledge

The Pandit and the Sadhvi: the Legend of Shraddha Mata

The Wealthy and the Business of Sahaj Yoga

Lives: Before Life and After Death

Sankaracharya versus the Mother

The Love-preaching Spiritualists Who Can’t Stand Rivals

I

n every religious community there are two distinct groups: one which strives for accommodation with other communities, the other which asserts its exclusiveness and superiority. Since the first group preaches peace and reasonableness and the other fanatical intolerance, the latter makes more noise, is more aggressive and succeeds in creating the impression that it is the real voice of the people. This is far from the truth. The most recent example is the hoo-ha created over perfectly innocuous remarks made by Abid Raza Bedar, Director of the Khuda Baksh Library of Patna on the release of a book by Dr S.M. Mohsin. Governor Shafi Qureshi was present at the function. All that Bedar said was that in his book Mohsin had clarified the meaning of Kafir. Many years earlier Bedar had himself written on the subject expressing the view that it was not correct to describe Hindus as Kafirs and there was nothing wrong in Muslims abstaining from eating beef to avoid hurting Hindu sentiment. This time elements which wanted to get Bedar out of his post grabbed the opportunity to mount a campaign against him. They got a Mulla-dominated institution to pronounce a fatwa against him and an Urdu rag called

Qaumi Tanzeem

to publish a series of victriolic attacks on him. Governor Shafi Qureshi and Mohsin were allowed to fade out of the scene; the only man they wanted as a sacrificial goat was Bedar. Enter Jagannath Mishra – as unscrupulous a politician as any today and equally adept in fishing in troubled waters. He sanctimoniously proclaimed himself being with his Muslim brethren i.e. with the unthinking mob which makes louder noise and has more votes.

Who is and who is not a Kafir is not as simple a matter as it may seem: the word means many things in English and Arabic. There is a variety of sorghum grown in Africa and America which goes under the same name. In the South African stock market there are shares known as Kafirs. But the commonest usage is from the Arabic meaning infidel. It was the meaning of the Arabic word which became an issue. It appears several times in the Holy Koran meaning ‘the covers’ i.e. one who hides or covers up the truth. In common Muslim parlance it refers to people who deny that Koran is the word of God and Mohammed was His Messenger. The Prophet used it as such “those who misbelieve (

walla zina Kafarun

) read all our signs lies. They are fellows of the Fire, they shall dwell within for ever.” The word was specifically used for Christians who believed in the Holy Trinity. The Koran says “they indeed are infidels who say God is

al Masihu Ibn Maryam

(the messiah son of Mary) … verily him who associates anything with God, hath God forbidden paradise, and his resort is Fire.” Islam lists five categories of Kafirs: those who do not believe in First Cause, those who do not believe in the Unity of God; those who do not believe in the revelation; idolators; and those who do not believe Mohammed was the Messenger of God.

Whatever be one’s views on the subject, there can be no two opinions on the principle that it is for an individual to affirm or deny what he believes to be the truth and no one has the right to denounce another as an infidel. No administration which adheres to secular ideals should yield to arm-twisting by bullies in the guise of upholders of religion –

mazhab kay theykeydar.

Bedar has become a symbolic figure. Patriotic Indians be they Muslims, Hindus, Christians or Sikhs must rally round him and frustrate evil designs of backward-looking fanatics.

11/7/1992

W

hat do Indians talk about most? God, money, politics and sex emerge as the top four favourites in the one-man public opinion poll I conducted last week. Of course, not in the order I have listed them. And with seasonal variations. When a catastrophe strikes or things start to go wrong, God tops. When all is tranquil, money manages to push God down to the second place. Politics (or the better Indian equivalent

partibaazi

) is a national obsession and at election time gets the better of both God and money. Likewise, sex, though it seldom gets the top ranking (few are willing to admit that they have sex on their tongues), manages to insinuate itself in most conversations whether it be about God and religion, money and the status money brings, politics and

partibaazi.

Since most Indians have sex on their minds rather than in their groins it finds more expression in speech than in action.

Another revelation that emerged from my field study in that whatever be the favourite topic of conversation, most Indians relate it to themselves. When they discuss God or religion, they emphasize their own religiosity or denigrate others as sanctimonious humbugs; when they talk of money it will be of their prowess in making it or of the unscrupulous methods adopted by those who have made more; when it is politics the undercurrent is always that politics is dirty business because it does not attract cleaner people like themselves. And when it is sex, although it is others that we strip naked, what runs though our tittle-tattle about it is the refrain that given the opportunity we could do better. The I is always triumphant.

It is a strange phenomenon that amongst a people who subscribe to the theory that the primary source of all evil is the ego, or

ahamkara,

the I runs through like a thread in the garland of all our conversation. And this when our Gods decried emphasis on the self. To wit Adi Sankara;

Manobuddhi, chittani,

Ahamkara naham

Chidananda roopa

Shivoham, Shivoham.

(I am not the mind, I am neither intelligence nor egoism I am the joy of intelligence, I am Shiva, I am Shiva.)

15/6/1982

W

e tend to judge religions by the lives and teachings of their founders; never by the conduct of those who profess to follow them. In effect we treat founding-fathers of religious cults much as we do race horses and place our money on our favourite. This is utterly lopsided. It is not very important to find out who was greater – Rama, Mahavir, Gautama, Christ, Mohammed or Nanak: they were perhaps equally great, but which community – Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Christians, Muslims or Sikhs produced more honest and courageous citizens. Consequently, although I study scriptures of all religions, I do not judge them by the loftiness of their teachings but by the impact they made on the taught.

I take greater interest in new cults than in established religions. Instead of having to accept myths and legends built round old prophets I can check on details of personal lives of their founders and study their impact on their following at first hand. There is nothing very new in anything that Sai Baba, Rajneesh, Anandmurti, Mahesh Yogi, Yogi Bhajan or anyone of the other of these latter-day Gurus have to say, but there are marked differences in the deportment and conduct of their followers. What they share in common is smug self-satisfaction and desire to gain converts. Rarely have I met one who would make me say, “What a good person his guru has made him!” The only exception I can think of are the Brahma Kumaris.

I first came to their notice about ten years ago. Sindhi ladies dressed in virginal white and vowed to celibacy were not my cup of religion. I read the literature they left with me. It was mostly a distillation of popular Puranic Hinduism. I saw an exhibition illustrating the teachings of their founder, Dada Lekh Raj. They were put across in conventional low-brow illustrations: good people dressed in white sitting

padmasan

on lotus flowers, swans floating around; bad people holding wine cups with scantily clad women ministering to them. Paradise was depicted as a new Vrindavan with gaily ornamented Krishna and Radha underneath a halo of coloured lights. It was not the sort of thing that would impress sophisticated men or women looking for spiritual sustenance. I was intrigued: Why had the movement caught on? What kind of people were drawn to it? What do they get out of it? Last week I found some of the answers to my questions at the Golden Jubilee celebrations at the headquarters at Mount Abu. The Ashram Express (named ‘Superfast’ was superlate by five hours) carried lots of foreign delegates: an English children’s dentist from Leeds, a German scientist, teachers, engineers and business people from Brazil, Australia, New Zealand and all parts of India. The

bandobast

at Mount Abu was flawless. Vegetarian food cooked by Brahmakumaris was wholesome and tasty. An atmosphere of genial goodwill pervaded the campus. No hustle-bustle, no breakdowns, no fraying of tempers. They described it as ‘Godly Service’ rendered to each other by people who regarded themselves as members of one joint family of Dada Lekh Raj. I had

darshan

of Dada’s daughter, Nirmal Shanta, daughter-in-law Prajendra, and the head of the organization Dadi Prakashmani, all extraordinarily beautiful ladies in their early seventies. I listened to Dadi Janki addressing assemblages of over 3000 people: it was a rare treat of dignified oratory heard in absolute silence. I asked my escort, a 23-year-old pretty Punjabi girl, Lata Khanna, working in the telecommunications department why instead of marrying (she could marry any Prince Charming of her choice) she had taken the vow of celibacy. She smiled as she replied: “I get all I want from meditation.” Even married members of the organization abstain from sex because, they say, it drains away energy required to meditate.