God’s Traitors: Terror & Faith in Elizabethan England (2 page)

Read God’s Traitors: Terror & Faith in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jessie Childs

36

. Henry Garnet’s last letter to Anne Vaux, 21 April 1606 © The National Archives, ref. SP 14/20, f.91

Principal Characters

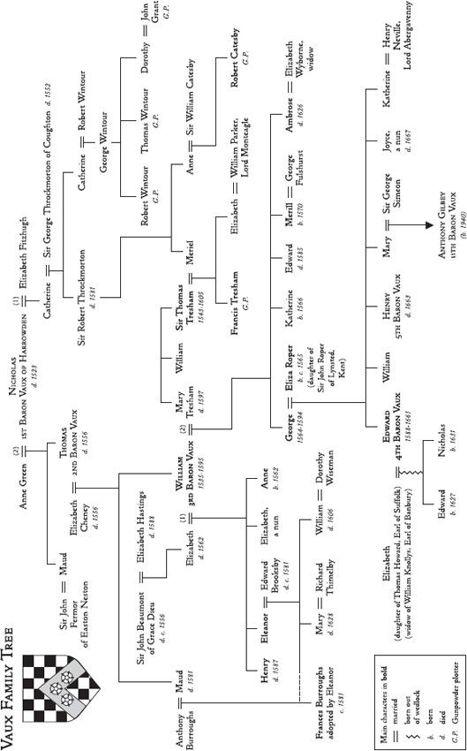

Members of the Vaux Family

William, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden

– the gentle patriarch. Father of:

Henry Vaux

– precocious child poet and Catholic underground operative, heir to the barony but ‘resolutely settled not to wife’

Eleanor Brooksby

– ‘the widow’

Anne Vaux

(

alias

Mistress Perkins) – ‘the virgin’

Frances Burroughs

– sprightly niece of Lord Vaux, adopted by Eleanor Brooksby upon the death of her mother

Mary, Lady Vaux

(née Tresham) – William’s second wife. Mother of:

Ambrose Vaux

– the black sheep

Merill Vaux

– youngest daughter of Lord Vaux, elopes with her uncle’s servant

George Vaux

– forfeits his right to the Vaux inheritance when he engages in a ‘brainless match’ with:

Eliza Vaux

(née Roper) – daughter of John Roper of Lynsted, Kent; possessor of ‘irresistible feminish passions’. Children include:

Edward

and

Henry

– the 4th and 5th Barons Vaux of Harrowden

Kinsmen and Friends

Anthony Babington

– Vaux associate, conspires to assassinate Queen Elizabeth in 1586

Robert Catesby

– Vaux cousin and leader of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot

Sir Everard Digby

– glamorous Catholic convert, late recruit to the Gunpowder Plot

Sir Thomas Tresham

of Rushton Hall – brother-in-law of Lord Vaux, recusant spokesman, father of a gunpowder plotter, architect, theologian, serial litigant

Priests

William Allen

– founder of the Douai/Rheims seminary and unofficial leader of the English Catholics in exile, supports the invasion of England by the powers of Catholic Europe

Claudio Aquaviva

, S.J. – Jesuit Superior General, based in Rome

Edmund Campion

, S.J. – former schoolmaster at Harrowden Hall, launches the Jesuit mission in England with Robert Persons

Henry Garnet

, S.J. – Jesuit Superior in England between 1586 and 1606; harboured by Anne Vaux and Eleanor Brooksby

John Gerard

, S.J. – ‘Long John with the little beard’, swashbuckling missionary harboured by Eliza Vaux

Edward Oldcorne

, S.J. – chaplain at Hindlip, Worcestershire

Robert Persons

, S.J. – first Jesuit missionary, later an exile agitating for a Catholic invasion of England

Robert Southwell

, S.J. – poet and polemicist, runs the London end of the mission, harboured by the Vauxes

Oswald Tesimond

, S.J. – confessor to several gunpowder plotters including the ringleader, Robert Catesby

Heads of State and Foreign Dignitaries

Elizabeth I

– Queen of England and Ireland, ‘Defender of the Faith’, daughter of Henry VIII

Guise, Henri, Duke of

– cousin of Mary Queen of Scots, founder of the French Catholic League, keen to dethrone Elizabeth I, assassinated in 1588

James VI and I

– King of Scotland and (from March 1603) King of England and Ireland, Protestant son of:

Mary Queen of Scots

– great-niece of Henry VIII, Catholic pretender to Elizabeth’s throne

Bernardino de Mendoza

– Spanish ambassador in London, 1578–84

Philip II

– King of Spain, widower of ‘Bloody’ Mary Tudor, imperialist for whom ‘the world is not enough’, sends the Great Armada against England in 1588

Pope Pius V

(1566–72) – excommunicates Queen Elizabeth in February 1570; ‘Impious Pius’ according to English Protestants

Pope Gregory XIII

(1572–85) – founder of the Gregorian calendar, supporter of various plots against Queen Elizabeth, sends the Jesuits to England in 1580

Pope Sixtus V

(1585–90) – endorses the 1588 Armada

Government Officials

Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley

– Lord Treasurer, Elizabeth’s chief minister and ‘spirit’. Father of:

Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

– Secretary of State to Elizabeth and James

Sir Edward Coke

– Attorney General, leads the prosecution in the Gunpowder Plot trials

Sir Walter Mildmay

– Chancellor of the Exchequer, Vaux neighbour, no friend to the ‘stiff-necked Papist’

Sir Francis Walsingham

– Elizabeth’s Secretary and spymaster

Richard Topcliffe

– priest-catcher, torturer, lecher

Richard Young

– chief London justice, in charge of the raid on the Vaux house in Hackney in November 1586

Others

Maliverey Catilyn

– government spy known as ‘II’

Richard Fulwood

– smuggler

John Lillie

– lay assistant to the missionary priests

Nicholas Owen

– ‘Little John’, builder of priest-holes

Thomas Phelippes

– Walsingham’s decipherer and forger

Sara Williams

– Lady Vaux’s teenaged maid, exorcised by the priests at Hackney in 1586, later Sara Cheney

Introduction

Four months after the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, Anne Vaux awoke in a prison cell. She had been on the run, changing her lodging every two to three days. Her confessor had hoped that she would have ‘kept herself out of their fingers’, but the authorities had tracked her down and taken her to the Tower of London. She was placed in solitary confinement and interrogated.

There were three chief lines of enquiry, all concerning Anne’s fraternisation with known, or suspected, conspirators.

1

The first focused on White Webbs, a house she kept in Enfield Chase. It had been used by her cousin, the plot’s ringleader, ‘Robin’ Catesby, as a rendezvous. One official called it ‘a nest for such bad birds’.

Who had been paying for the house’s upkeep? Anne’s interrogators demanded.

Who had visited?

When?

What had they talked about?

Where else had she stayed and with whom?

Anne was pressed about the pilgrimage she had recently undertaken with several of the conspirators and their families to St Winifred’s Well in Wales.

When did she go?

With whom?

What had been the purpose of the trip and where had they lodged?

Had she seen or heard anything to make her suspicious?

And what had some of the wives meant when they had asked her where she would bestow herself ‘till the brunt were past, that is till the beginning of the Parliament’?

Finally, Anne was asked about Garnet: Father Henry Garnet

alias

Measy,

alias

Walley,

alias

Darcy,

alias

Farmer,

alias

Roberts,

alias

Philips: the superior of the Society of Jesus in England.

What advice had she heard him give the traitors?

Why, after he had been proclaimed a ‘practiser’ in the plot on 15 January 1606, had she helped him evade arrest?

Why, after his capture twelve days later, had she followed him to London and sent him secret letters etched in orange juice?

And what was the nature of their relationship? Was she his sister? Benefactor? Confederate? … Lover?

Anne’s nerve had been tested many times. She had faced down spies in her household, slurs against her name and raids on her home. She was well lessoned in the art of equivocation and had heard enough prison tales to have some expectation of her treatment. But nothing could prepare her for the indignity of incarceration, nor the odium concentrated upon those Catholics suspected of involvement in the plot to annihilate King James I, his family and the political and spiritual elite of the realm.

It was reported that ‘to more weighty questions she responded very sensibly’. She revealed the names of some of her house guests, though was hazy on ‘needless’ details, and she admitted that her suspicions had been raised on the pilgrimage, when she had feared that ‘these wild heads had something in hand’. But when her interrogators accused her of impropriety with her priest, Anne’s manner shifted. She ‘laughed loudly two or three times’, then rounded on them:

‘You come to me with this child’s play and impertinence, a sign that you have nothing of importance with which to charge me.’

Of course, she sneered, she had known about the powder treason. She was, after all, a woman, and women make it their business to know everything. And of course Garnet had been involved: since he was the greatest traitor in the world, he wouldn’t have missed it. Then she thanked her guards for giving her board and lodging, as no one else in London was prepared to put her up.

‘She is really quite funny and very lively,’ wrote an admirer. ‘She pays no attention whatsoever to them, and so she has them amazed and they are saying, “We absolutely do not know what to do with that woman!”’

*

That woman

was one of several ardent, extraordinary, brave and, at times, utterly exasperating members of the Vaux

fn1

family. In many ways they were perfectly typical of the lower ranks of the Elizabethan aristocracy. They owned grand houses and estates. They patronised local people and places. They married folk similar to themselves. William, third Baron Vaux, was a gentle soul, seldom happier than with his hounds and hawks. He was a proud father, an affable host, a bit deaf and not good with money. His eldest daughter, Eleanor, was a ‘very learned and in every way accomplished lady’; his youngest, Merill, ran off with her uncle’s servant. One grandson inherited the barony and married the daughter of an earl; another murdered a merchant in Madrid.

There were squabbles within this family and disputes without it. There were heady romances, clandestine marriages and some very embarrassing lawsuits. There was even the proverbial black sheep: ever-indebted Ambrose, ‘an untoward and giddy headed young man’, who took to brawling at Shakespeare’s Globe.

2

The private lives of other Elizabethan families were probably just as entertaining, if not so well documented. The Vauxes were not, in other words, unique. But there was something that made them remarkable, that defined them and in turn helps them define the age in which they lived, for it was the ill fortune of the Vaux family, at a time of Protestant triumphalism, to be Roman Catholic.

Specifically, the Vauxes were ‘recusants’. They refused to go to church every Sunday (the word stems from the Latin

recusare

: to refuse). Not for them the awkward compromises, the crossed fingers and blocked ears at official service, the hasty confession and secret Mass at home afterwards. Once the men in Rome decreed that it was not good enough to be a ‘church papist’, as those who chose outward conformity were derisively termed, the Vauxes stayed at home. They needed the sacraments. They needed to confess their sins and consume what they believed to be the real presence of Christ at the Sacrifice of the Altar, but this required an agent of sacramental grace. Here was another problem, since Catholic priests were effectively outlawed. So for upholding their faith, the Vauxes committed the passive crime of not going to church and the more active one of harbouring priests. Other laws passed during the reign of ‘Good Queen Bess’ banned the

receipt of images, crucifixes, rosaries and other ‘popish trash’ that was so ingrained in the Catholic way of life.

The penalties for disobedience – for what was widely perceived as a challenge to monarchical authority and a deliberate fracturing of society – were fines, controls on movement, the loss of public office, property, liberty and, in some cases, loss of life. Few Elizabethans would have disputed that obedience was a Christian duty, but after the Pope excommunicated Queen Elizabeth in 1570, it became increasingly difficult for English Catholics to maintain a dual allegiance to their God and their Queen.