Good Cook (19 page)

Authors: Simon Hopkinson

serves 2

7–9 oz dry white wine

2 tbsp tarragon vinegar

1 small carrot, very thinly sliced

1 small white onion, very thinly sliced

a few black peppercorns

½ tsp coriander seeds

2 large pinches of sea salt

a bay leaf, some parsley stalks, a sprig or two of thyme

pinch of sugar

2 spanking fresh mackerel, gutted and cleaned, heads removed

4–5 thin slices of lemon

A truly classic dish of the French repertoire, maquereau au vin blanc is mostly to be found on bistro or brasserie menus of the old school. However, it was once also a favorite dish prepared in the home, where a diligent mother would have purchased the finest, freshest summer mackerel from a market stall in a Norman or Breton fishing port. And let us hope that she still does such a thing. It is one of the simplest cold fish dishes to put together, rewarding the cook with a deeply tasty result: soft flakes of almost sweet-tasting fish, swimming in nicely aromatic juices. And so very inexpensive, too. Only use mackerel that are spanking fresh, for best results.

Preheat the oven to 350°F.

Apart from the mackerel and lemon, put all the ingredients into a stainless steel pan and bring up to a simmer. Cook for 10–15 minutes, or until the carrot is almost cooked. Place the mackerel in a lidded dish where they will fit snugly. Lay the lemon slices over the fish and pour over the hot wine/vinegar liquid, including all its aromatics. Pop on the lid and cook in the oven for about 20 minutes, or until the mackerel are clearly cooked; test them with a small fork, carefully looking inside the cavity of the fish, where the flesh should be opaque and white. Leave to cool completely, then put into the fridge until needed. Personally, I like them really quite cold, but served with hot, small new potatoes (peeled, naturally), nicely buttered, and with lots of finely chopped parsley added too.

serves 4

approx. 1¼ lb piece of immaculately trimmed sirloin of beef

sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

for the mayonnaise

2 egg yolks

2 tsp smooth Dijon mustard

salt and freshly ground white pepper

10 oz sunflower or other neutral oil

juice of ½ a large lemon

5 oz light olive oil

for the sauce

4 tbsp homemade mayonnaise (see below)

1–2 tsp Worcestershire sauce

juice of ½ a small lemon, or a touch more

approx. 2 tbsp milk

salt and freshly ground white pepper

Here is Arrigo Cipriani talking about Carpaccio in

The Harry’s Bar Cookbook

(Smith Gryphon, 1991): “Carpaccio is the most popular dish served at Harry’s Bar. It is named for Vittore Carpaccio, the Venetian Renaissance painter known for his use of brilliant reds and whites. My father invented this dish in 1950, the year of the great Carpaccio exhibition in Venice. The dish was inspired by the Contessa Amalia Nani Mocenigo, a frequent customer at Harry’s Bar, whose doctor had placed her on a diet forbidding cooked meat.”

“Carpaccio,” Signor Cipriani goes on to say, “[which] has been copied by any number of good restaurants all over the world, is made by covering a plate with the thinnest possible slices of raw beef and garnishing it with shaved cheese or an olive oil dressing. The genius of my father’s invention is his light, cream-coloured sauce that is drizzled over the meat in a crosshatch pattern.”

And how true. This original Carpaccio is, without doubt, a dish of genius. If you have never eaten the one in Venice, then why not try it at home. Here is how to do it. The following recipe is based upon the one served at Harry’s Bar.

Note: I usually find that thinly sliced sirloin, nice and red, trimmed of all fat and sinew and cut from a whole piece, is best, here. You will also need to make some mayonnaise for the base of the sauce. The recipe will yield more than you need, but it is always good to have some in the fridge. A hand-held electric mixer is best for the making of mayonnaise.

For the mayonnaise, put the egg yolks into a roomy bowl and mix in the mustard and some seasoning. Beginning slowly, beat together while very slowly trickling in the sunflower oil. Once the mixture is becoming very thick, add a little lemon juice. Continue beating, adding the oil a little faster now while also increasing the speed of the whisk. Once the oil has been exhausted, add some more lemon juice and then begin incorporating the olive oil. Once this has also been used up, add a final squeeze of lemon juice; the texture should be thick and unctuous. Taste for seasoning, then pack into a lidded plastic container and keep in the fridge until ready to use.

Now you have the mayonnaise, you can make the Carpaccio sauce. Simply whisk all the ingredients together in a small bowl until pourable, but not too runny; the traditional look of the dish needs the cross-hatch pattern of the sauce to remain in place, not spreading out over the meat. On more than one occasion, in my kitchen, I have miscalculated the correct texture, so, as ever, practice makes perfect.

To serve the Carpaccio, slice the sirloin as thinly as you possibly can, using a thin, very sharp long knife. Place 1 slice of meat between a fold of waxed paper (or plastic wrap), and gently beat thinner with, say, a rolling pin. Peel off the beef and arrange on a plain white, main-course size plate. Repeat this process and add to the first slice, pushing it up against the first one; 2–3 slices should be sufficient for one serving. Once you have a neat, roughly circular arrangement of meat, move on to the next plate, and so on. Finally, pour the sauce into a bottle and affix a pourer—of the type that you may use for a bottle of olive oil. Deftly, and swiftly, criss-cross the Carpaccio with the sauce, sprinkle on a touch of Maldon (or other) sea salt and a brief grind from the pepper mill. Serve promptly. And I prefer to eat this just as it is; no further garnish necessary.

Incidentally, I once wrote about the Harry’s Carpaccio in the

Independent

newspaper, about fifteen years ago now. The same Mr. Jason Lowe took the pic for it then, with me banging on incessantly in the text about the red and white colors in the dish (see the Cipriani introduction). Blow me, can you believe that on this particular occasion a gremlin in the works of newspaper printing pulled a fast one: the picture emerged in black and white. Well… eventually, we laughed.

serves 4

for the pastry

¾ cup lard, cut into small pieces then frozen for 10 minutes

1¾ cups all-purpose flour

salt

3–4 tbsp iced water

for the filling

12 oz stewing steak, cut into

1

/

3

in dice

5 oz ox (or other) kidney, cut into

1

/

3

in dice

7 oz chopped onion

7 oz diced peeled potato

salt and plenty of freshly ground white pepper

1 tbsp all-purpose flour

approx. 3 oz cold water

a little milk, for glazing the pastry

A nod, here, to the kind of pie that I always wanted to grab and eat from northern market stalls as a boy. The kind of individual pie of which I speak, “Meat and Tatie Pie” (’tatie being potato, in the vernacular) smelt so very good that I could easily have wolfed down two or three at nine in the morning, aged ten. But, no. My dear, late mother would never have countenanced such a thing. In the mildest, Hyacinth Bucket kind of way, we were not the kind of family who bought meat and “tatie pies from market stalls. Although she bought every kind of finest fresh fish, vegetable, fruit, cheese and, occasionally, black pudding from various favorite mongers, to purchase something that was always proudly made by her at home, and to

her

mother’s recipe, was anathema. So it was not until about ten years ago that I first bit into one.

Well, I am here to tell you that they were absolutely fantastic. Warm and juicy, the flakiest pastry, the whiff of onion somewhere, and so much white pepper (ready-ground, naturally) in there it would catch your breath. Mum made a big, deep pot of pie when moved so to do, but there was only ever a top crust. Delicious as it most surely was—and I can taste it now—the best thing about those individual market pies was the all-enveloping pastry: all top. And sides. And bottom, too. The recipe that follows has this, but also some

kidney in it, too, which I think is rather nice. The lady of the house, however, may well have not approved …

You will need a tart tin with a removable bottom, measuring 1½ in deep by 8 in wide, lightly greased. Also, a flat oven tray; to put into the oven to heat up, so that the base of the pie will cook through evenly.

To make the pastry, rub together the fat, flour and salt until it resembles coarse breadcrumbs. Quickly mix in the water and work together until you have a coherent mass. Knead lightly and put into a plastic bag. Leave to rest in the fridge until the filling has been prepared.

Preheat the oven to 400°F.

Put all the ingredients for the filling—except the water and milk—into a roomy bowl and mix together well with your hands. Divide the pastry into two-thirds and one-third size pieces. Roll the larger piece into a circle about

1

/

8

in thick—it does not want to be too thin. Line the pan, leaving the overhang intact. Roll out the rest of the pastry for the lid and set aside. Pile the filling in right to the top and carefully pour in the water, which should only just reach the surface. Brush the edge of the overhanging pastry with milk and put on the lid. Press the edges together at the rim of the pan and then slice off the excess pastry with a knife.

Brush the surface with milk, then decorate and further press the edges together with the tines of a fork. Make 2 incisions in the center of the pie and place on the tray in the oven. Cook for 25 minutes, then turn the temperature down to 300°F. Bake for a further hour, checking from time to time that the pastry is not browning too much; if it is, loosely cover with a sheet of kitchen foil. Remove from the oven, allow to rest for 10 minutes, then cut into wedges. Very good indeed with pickled red cabbage or piccalilli.

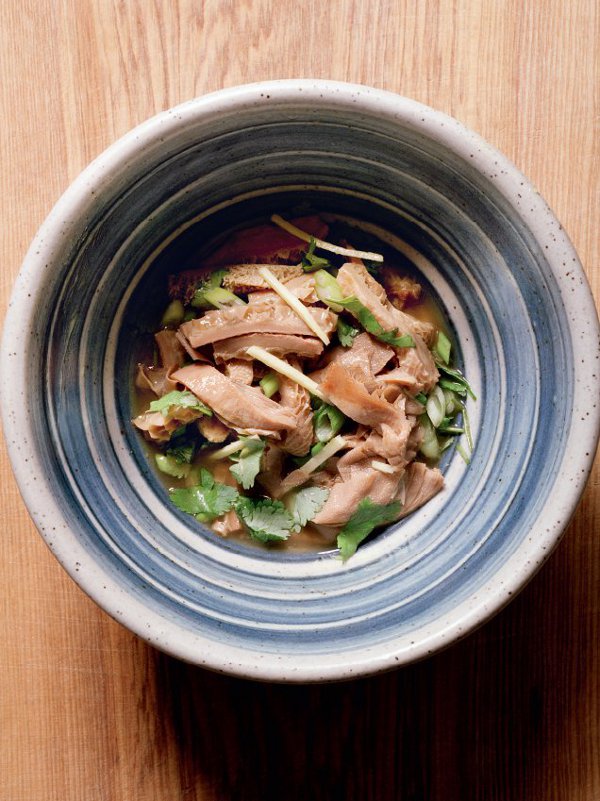

generously serves a healthy 2—who love tripe

5–6 dried shiitake mushrooms, left whole

3½ cups chicken stock

2¼ lb beef tripe, cut into thick strips, briefly blanched in boiling water, then drained

7 oz Chinese rice wine

3 oz fresh ginger, peeled and cut into thick slices

1 large onion, quartered

4 cloves of garlic, unpeeled and bruised

2 star anise

to finish the dish

2 small spring onions, trimmed and cut into slivers

1 thumb-size piece of fresh ginger, peeled and cut into thin matchsticks

1 mild green chilli, thinly sliced

1–2 tbsp coriander leaves, roughly chopped

a dash or two of light soy sauce, to taste

1 tsp potato flour, slaked with a little rice wine (optional)

I really, really wish that more folk could get their head around the idea of eating tripe. Yes, it is an acquired taste: all at once of a deep and worryingly unusual fragrance, together with a texture that will be new to the uninitiated but, I hope, would grow into a favorite kind of bouncy tender.

And, what’s more, I don’t know any gourmet chums of mine who don’t enjoy tripe. Oh, actually, no, there is just one, the chef and my friend Rowley Leigh. He ain’t too fond of it, nor does he enjoy the extra-deep taste of a French andouillette, that “whiff of the farmyard” tripe sausage that can divide a lunch table into those who do and those who can’t at all contemplate this rude food. Tripe is also supposed to be good for you, but that will always be secondary to the texture and flavor for me.

In London, I buy my beef tripe from two purveyors. The most convenient for me is in Shepherd’s Bush market, which boasts a few halal butchers, all of which sell tripe in various forms; there is even goat tripe in one of them.

The other place I visit is a Chinese supermarket in Lisle Street, Chinatown, in London’s West End. Here, they sell packets of frozen tripe, one labeled “manifold,” the other “honeycombe,” with the latter being the most commonly recognized type. I usually buy one of each, if up West.

Put the shiitake mushrooms in a bowl, then boil a ladle or two of the chicken stock and pour it over them. Leave to soak for 30 minutes. Put the tripe into a solid-based lidded pot, add the rice wine, the mushrooms (with their stock), the rest of the chicken stock, the ginger, onion, garlic and star anise. Stir together, bring up to a very quiet simmer and cook for at least 2 hours, or until very tender indeed (you could cook the tripe in a very low oven, if you prefer, at 275°F.

Using a slotted spoon, lift out the tripe and put it into another pan. Strain the cooking liquor over it and discard all debris. Reheat the tripe and add the finishing spring onions, ginger, chilli and coriander leaves. Season with a little soy sauce and, if you think it necessary, very lightly thicken the sauce with the slaked potato flour. Serve at once, with plainly boiled rice.