Goodbye, Darkness (6 page)

But the perennial student's cherry orchard came down, and my undergraduate years were abruptly interrupted on December 7, 1941. In the spring of 1942, guided by the compass that had been built into me, I hitchhiked to Springfield and presented myself at the Marine Corps recruiting station, a cramped second-story suite of rooms with a superb view of a Wrigley's billboard and the Paramount Theater parking lot. The first test was weight, and I flunked it. There wasn't enough of me. The sergeant, or “Walking John,” as the Corps called recruiting NCOs, suggested that I go out, eat all the bananas and drink all the milk I could hold, and then come back. I did. I made the weight. Immediately thereafter I was sick. My liver, colon, and lungs — all my interior plumbing — fused into a single hard knot and wedged in my epiglottis. The sergeant held my head over a basin as I threw up banana after banana, and he said, not unkindly, “Just keep puking till you feel something round and hairy-like coming up. Keep that. That's your asshole.” I recovered and continued with the exam. Meanwhile all that milk was working its way through my system. My back teeth were floating. At last the end was in sight. A pharmacist's mate nodded at a rack of twenty-four test tubes and told me to go over in the corner and give him a urine specimen. But once I started, I couldn't stop. I returned and handed him twenty-four test tubes, each filled to the brim with piss. He looked at the rack, looked at me, and then back at the rack again. An expression of utter awe crossed his face. It was the first misunderstanding between me and the Marine Corps. There would be others.

Arizona, I Remember You

D

uring the interval between my father's death and the out

-break of war in the Pacific, my loss of perception had been matched by American ignorance of the threat in the Far East. The United States was distracted by the war in Europe, with Hitler's hammer blows that year falling on Yugoslavia, Greece, Crete, and — the greatest crucible of suffering — Russia. Virtually all Americans were descended from European immigrants. They had studied Continental geography in school. When commentators told them that Nazi spearheads were knifing here and there, they needed no maps; they all had maps in their minds. Oriental geography, on the other hand, was (and still is) a mystery to most of them. Yet the Japanese had been fighting in China since 1931. In 1937 they had bombed and sunk the U.S. gunboat

Panay

on the Yangtze and jeered when the administration in Washington, shackled by isolationism, had done nothing. Even among those of us who called ourselves “interventionists,” Hitler was regarded as the real enemy. It was Hitler Roosevelt had been trying to provoke with the Atlantic Charter, the destroyer swap with Britain, Lend-Lease, and shoot-on-sight convoys, each of which drew Washington closer to London. Europe, we thought, was where the danger lay. Indeed, one of my reasons for joining the Marine Corps was that in 1918 the Marines had been among the first U.S. troops to fight the Germans. Certainly I never dreamt I would wind up on the other side of the world, on a wretched island called Guadalcanal.

Roosevelt never changed his priorities, but when the Führer refused to rise to the bait, the President found another way to lead us into the war — which was absolutely essential, he felt, if the next generation of Americans was to be spared a hopeless confrontation with a hostile, totalitarian world. On September 27, 1940, the Japanese had signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. That opened the possibility of reaching the Axis through Tokyo. And Roosevelt knew how to do it. During the four months before the pact, the fall of France, Holland, and Belgium had wholly altered the strategic picture in Asia. Their colonies there were almost defenseless, but FDR let it be known that he felt avuncular. Even before the Tripartite Pact he had warned the Japanese to leave French Indochina alone. Once the Nipponese tilted toward the Axis, he proclaimed an embargo on scrap iron and steel to all nations outside the Western Hemisphere, Great Britain excepted. He reached the point of no return in the summer of 1941. On July 24 Jap troops formally occupied Indochina, including Vietnam. Two days later the President froze all Japanese credits in the United States, which meant no more oil from America. Britain followed suit. This was serious for the Japanese but not desperate; their chief source of petroleum was the Netherlands East Indies, now Indonesia, which sold them 1.8 million tons a year. Then came the real shock. The Dutch colonial government in Djakarta froze Japanese assets there — and renounced its oil contract with Dai Nippon (“Dai” meaning “Great,” as in Great Britain). For Prince Fumi-maro Konoye, Emperor Hirohito's premier, this was a real crisis. Virtually every drum of gas and oil fueling the army's tanks and planes had to be imported. Worse, the Japanese navy, which until now had counseled patience, but which consumed four hundred tons of oil an hour, joined the army in calling for war. Without Dutch petroleum the country could hold out for a few months, no more.

Konoye submitted his government's demands to the American ambassador in Tokyo: If the United States would stop arming the Chinese, stop building new fortifications in the Pacific, and help the emperor's search for raw materials and markets, Konoye promised not to use Indochina as a base, to withdraw from china after the situation there had been “settled,” and to “guarantee” the neutrality of the Philippines. Washington sent back an ultimatum: Japan must withdraw all troops from China and Indochina, withdraw from the Tripartite Pact, and sign a nonaggression pact with neighboring countries. On October 16 Konoye, who had not been unreasonable, stepped down and was succeeded by General Hideki Tojo, the fiercest hawk in Asia. The embargoed Japanese believed that they had no choice. They had to go to war unless they left China, a loss of face which to them was unthinkable. They began honing their ceremonial samurai swords.

All this was known in Pennsylvania Avenue's State, War, and Navy Department Building. The only question was where the Nips would attack. There were so many possibilities — Thailand, Hong Kong, Borneo, the Kra Isthmus, Guam, Wake, and the Philippines. Pearl Harbor had been ruled out because Tojo was known to be massing troops in Saigon, and American officers felt sure that these myopic, bandy-legged little yellow men couldn't mount more than one offensive at a time. Actually they were preparing to attack

all

these objectives, including Pearl, simultaneously. In fact, the threat to Hawaii became clear, in the last weeks of peace, even to FDR's chiefs of staff. U.S. intelligence, in possession of the Japanese code, could follow every development in Dai Nippon's higher echelons. On November 22 a message from Tokyo to its embassy on Washington's Massachusetts Avenue warned that in a week “things are automatically going to happen.” On November 27, referring to the possibility of war, the emperor's envoy to the United States asked, “Does it seem as if a child will be born?” He was told, “Yes, the birth of a child seems imminent. It seems as if it will be a strong, healthy boy.” Finally, on November 29, the U.S. Signal Corps transcribed a message in which a functionary at the Washington embassy asked, “Tell me what Zero hour is?” The voice from Tokyo replied softly: “Zero hour is December 8” — December 7 in the United States — “at Pearl Harbor.”

The Americans now knew that an attack was coming, when it would come, and where. The danger could hardly have been greater. Japan's fleet was more powerful than the combined fleets of America and Great Britain in Pacific waters. U.S. commanders in Hawaii and the Philippines were told: “This dispatch is to be considered a war warning. … An aggressive move by Japan is expected within the next few days.” That was followed on December 6 by: “Hostilities may ensue. Subversive activities may be expected.” The ranking general in Honolulu concluded that this was a reference to Nipponese civilians on Oahu. Therefore, he ordered all aircraft lined up in the middle of their airstrips — where they could be instantly destroyed by hostile aircraft. The ranking admiral decided to take no precautions. Put on constant alert, he felt, his men would become exhausted. So officers and men were given their customary Saturday evening liberty on December 6. No special guards were mounted on the United States Fleet in Pearl Harbor — ninety-four ships, including seven commissioned battleships and nine cruisers — the only force-in-being which could prevent new Japanese aggression in Asia. Only 195 of the navy's 780 antiaircraft guns in the harbor, and only 4 of the army's 30 antiaircraft batteries, were manned. And most of them lacked ammunition. It had been returned to storage because it was apt to “get dusty.”

In the early morning hours of Sunday, December 7, 1941, as Americans slept off hangovers in Waikiki amid the scent of frangi-pani, the squawk of pet parrots, and the echo of surf on Diamond Head, two hundred miles north of them a mighty Japanese armada steamed southward at flank speed. Altogether there were 31 pagoda-masted warships, but the thoughts and prayers of all the crews were focused on the 360 carrier-borne warplanes, especially those in the lead attack squadron aboard the flattop

Akagi

. The squadron leader was told that if he found he had taken the enemy by surprise, he was to break radio silence over Oahu and send back the code word

tora

(tiger).

In darkness the pilots scrambled across the

Akagi

's flight deck to their waiting Nakajima-97 bombers, Aichi dive-bombers, and Kaga and Mitsubishi Type-O fighters — the swift, lethal raiders which the Americans would soon christen “Zeroes.” Zooming away, they approached Kahuku Point, the northern top of Oahu, at 7:48

A.M.

and howled through Kolekole Pass, overlooking the U.S. Army's Schofield Barracks, thirty-five miles from Honolulu. Luck rode with them: an overcast cleared and the sun appeared in a rosy satin dawn, sending warm pencils of light shining down on the green valleys and green-and-brown canebrakes, the purplish spiny mountain ridges, and the brilliant blue sea, rimmed by valances of whitecaps. Dead ahead, on Oahu's southern coast, lay their targets: Wheeler, Bellows, Ewa, and Hickam airfields and, most important, the magnificent port which the ancient Hawaiians had christened

Wai Momi

— “water of pearl.” There American battlewagons lay anchored in groups of two off Ford Island, in the center of the harbor: the

California, Maryland, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia, Arizona, Nevada

, and the thirty-three-year-old

Utah

, now retired from active service.

At the Japs' height, ten thousand feet, they looked like toy boats in a bathtub. Swinging at chains around them, hemming them in and making an escape almost impossible, were eighty-six other vessels, concentrated in an area less than three miles square. Even if the men-of-war could maneuver around them, the one channel to the sea and freedom was barred by a torpedo net. The Japanese commander signaled his squadron: “

To-, to-, to,

” the first syllable of

totsugeki

, “Charge!” Then he signaled the

Akagi: “Tora, tora, tora!”

Then, back to his air fleet: “

Yoi!

” (“Ready!”) and “

Te!

” (“Fire!”). Flying at treetop level and defying the pitifully few dark-gray bursts of flak polka-dotting the serene sky, successive waves of Nip aircraft skimmed in over Merry Point, attacking and wheeling to return again and again. Zeroes strafed; dive-bombers and torpedo bombers dropped missiles and sticks of dynamite through the roiling, oily, reeking clouds of smoke, knocking out 347 U.S. war-planes and 18 warships, among them all the battleships, the cruisers

Helena

and

Honolulu

, and the destroyers

Cassin

and

Downes

. At a cost of 29 planes the Nips killed or wounded 3,581 Americans, nearly half of them on the sunken

Arizona

.

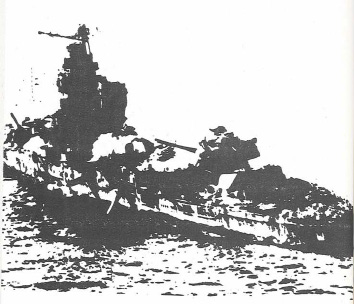

The destruction of the

Arizona

, which had been moored in tandem with the repair ship

Vestal

, was the most spectacular loss. A bomb set off fuel tanks, which ignited eight tons of highly volatile black powder — stored against regulations — and that, in turn, touched off vast stocks of smokeless powder in a forward magazine before it could be flooded. Instants later three more bombs, including one right down a funnel, found their targets. As over a thousand U.S. bluejackets were incinerated or drowned, the 32,600-ton battlewagon sent up 500-foot-high cascades of flame, leapt halfway out of the water, broke in two, and plunged to the muddy bottom, her vanishing forecastle enshrouded in billowing clouds of black fumes. Not even Kukailimoku, the war god of ancient Havai'i, had envisioned such a disaster. “Remember Pearl Harbor” became an American shibboleth and the title of the country's most popular war song, but it was the loss of that great ship which seared the minds of navy men. Six months later, when naval Lieutenant Wilmer E. Gallaher turned the nose of his Dauntless dive-bomber down toward the

Akagi

off Midway, the memory of that volcanic eruption in Pearl Harbor, which he had witnessed, flashed across his mind. As the

Akagi

blew up, he exulted: “

Arizona, I remember you!

”