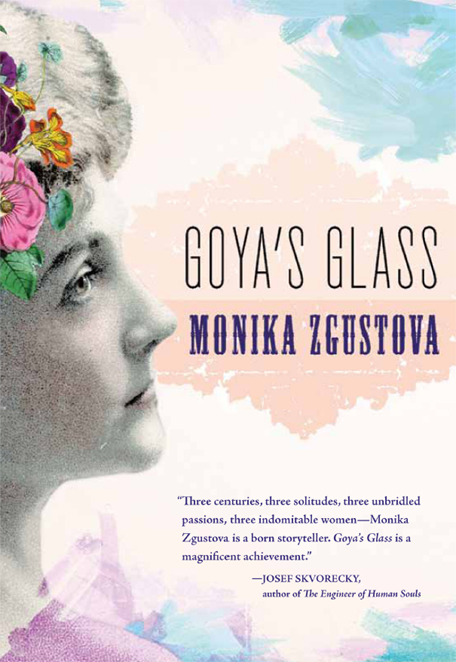

Goya's Glass

Authors: Monika Zgustova,Matthew Tree

Tags: #Literary, #Biographical, #General, #Fiction

MONIKA ZGUSTOVA

TRANSLATED BY MATTHEW TREE

Published in 2012 by the Feminist Press

at the City University of New York

The Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue, Suite 5406

New York, NY 10016

Translation copyright © 2012 by Matthew Tree

All rights reserved.

Originally published as

Grave cantabile

by Odeon-Euromedia Group in Prague in 2000, and

La dona dels cent comriures

by Proa in Barcelona in 2001.

No part of this book may be reproduced, used, or stored in any information retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the Feminist Press at the City University of New York, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant

from the Institut Ramon Llull.

Cover design by Faith Hutchinson

Text design by Drew Stevens

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zgustova, Monika.

Goya’s glass / by Monika Zgustova.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-55861-798-8

1. Alba, María del Pilar Teresa Cayetana de Silva Alvarez de Toledo, duquesa de, 1762-1802—Fiction. 2. Goya, Francisco, 1746-1828—Fiction. 3. Nemcovâ, Božena, 1820-1862—Fiction. 4. Berberova, Nina Nikolaevna—Fiction. I. Title.

PG5039.36.G87G68 2012

891.8'6354—dc23

2012015164

Passages in this novel attributed to

Francisco Goya, Božena N

ě

mcová, and Nina Berberova

are derived from historical texts.

F

or the last time. For the last time, meaning never again.

For the last time. How many times have I pronounced these words as a threat? I used to think of them as words like any others, insignificant, featherweight. I played with them as a child with her doll, like a lady with her fan. Only on that one occasion, when I said them in front of him, did these words become the chimera of a nightmare, a monster with bat’s wings and donkey’s ears, with a beak and claws designed to inflict punishment, and when it has finally abandoned its horrible task, flies off with a heavy heart, as if reluctantly leaving a trail of incense and sulfur.

For the last time . . . There was just one candle lit. The light avoided the corners, the walls dripped with humidity and darkness. I thought that I had come in vain. The emptiness without his presence frightened me at first, but then left me feeling relieved. I had made the journey to his house on foot at a hurried pace, stopping every now and again, determined each time not to go one step further. I had gotten rid of my carriage because I couldn’t simply sit there without doing anything, just shouting

at the driver to go faster and thinking, heaven help me, let him run over whomever in the happy crowd might be blocking our path. The happiness of others struck me as unbearable, out of place, and I jumped from the carriage so as to go ahead on foot. I was desperate.

I reached his house without feeling the pain in my feet. Of course, Venetian slippers covered in emeralds are not made for trotting through the badly paved streets of Madrid. I climbed up to the third story with my skirt raised up above my knees. I cared not if the neighbors saw me. Desperation and anguish made me run as if I were fleeing from a gaggle of cackling geese.

Darkness reigned in the spacious room of stone and the little flame of the candle lit up only the small space immediately around it. Wherever you looked there were half-painted canvases, like white monsters, full of folds and wrinkles. Little by little I grew accustomed to the shadows, and amid all the folders, paints, and pots, I found a carafe of wine and poured myself a little. In the candlelight, the Manzanilla looked like honey in its glass. At that moment I smelled the familiar odor of bitter almonds and heard the creak of a bench from which a man was rising drowsily. In the shadows, the barely visible figure tied up his shirt and trousers. Before entering the circle of light from the candle, I smelled his odor as he shifted in his sleep. So he was there! I was overcome by a feeling of relief, just as his absence had been a relief to me a moment ago. So powerfully could he move me! Suddenly something whispered to me that I should punish him for making me suffer in this way, that I should show him who I was. He didn’t give me time to do anything but took

hold of me with his large hands that sunk into my back like claws. We were standing, sitting, lying, sitting again, he with his claws forever dug into my face, in a sweet violence that made me feel lost. And when I came to again, he was bending over me, nursing the wounds that the long race through the streets of Madrid had left on my feet, licking off the blood as a mother bear does with her cubs.

For the last time . . . These words came back, they grew between us, a monstrous bat that beat its wings blindly against the walls. Was it he who spoke them? No. I myself released the monster from its cage. The need to punish the man in the unlaced shirt was uppermost in me. But the bat flew out of the room of stone; it followed me when I went down the stairs, when I was fleeing. Fleeing? And the man with the creased shirt stood at the threshold of the door. His wide shoulders slumped; his hair, twisted like a nest of snakes, hung lifeless. I turned around, perhaps to tell him something, perhaps—yes, that was it!—to take back those words, to withdraw them, to cancel them out, but he had already closed the door after saying, with indifference: Go, and don’t catch cold.

I simply cannot stand healthy people. The maids and chambermaids run up and down, and what is it with them that they don’t realize that I have no wish to see their pale delicate legs? That I don’t want them to bring me hot chocolate with ladyfingers in bed because I simply cannot bear the sight of those flexible, smelly hands of theirs, with their pink nails? I don’t want roses or

gladioli, I don’t want anything that is beautiful and bursting with health, when I, here in my bed, smell the rancid, sweetish smell of my body, which has surely begun to decompose even though it is still full of life. People’s day-to-day pleasures have always irritated me and I would now quite happily tear the Venetian crystal vases full of flowers from the hands of the chambermaids; I would smash them against the floor until they shattered, then I would grab the girls by their hair and drag them so that the pieces of glass tore at their pretty, healthy faces, so that the scars would remain engraved on their faces forevermore in memory of the Duchess of Alba.

But I cannot do it, I cannot get up, and when I want to write a few lines or read for a while, two maids have to hold me up like a dead weight so that a third may place some large cushions behind my back. Yes, all these pretty girls will still be around after the Duchess of Alba has taken her leave, just as, some time ago, her father ceased to be, and then in turn her stepfather, her mother, and worst of all her grandfather. I am still looking for him, even today. The woman who everyone has desired—all men, without exception—will disappear. Once a year has gone by, who will remember what

le chevalier

of Langre, that unbearable Frenchman, wrote about me, when he said that each one of my hairs gave rise to outbursts of passion? And that when I walked along the street, the people, stunned, leaned out of their windows, and children stopped playing to observe me? All of that has finished forever. The coveted woman will die, she and her passions, her pains and her satisfactions, and with her a whole world will disappear. Nothing of it will survive; the only

thing that might remain are his pictures. Yes, it is in them that I will live forever: the duchess, the perfidious beauty, the vice-ridden duchess, the duchess-harlot, converted into the witch who flies above the heads of men. That is what will remain of me, that and nothing else.

And now what are you bringing me, darling? The thing is heavy; watch out you don’t slip on the carpet. You are smiling at me. Come close, yes, yes, closer, closer. Ah, a deep crystal bowl full of rose water and water lilies: Are you bringing it so that the odor of my body should become even more obvious? Is that what you want?

Now she has turned to draw the curtain of the bed. All I would have to do is to pull on the cloth covering the bedside table, like this, yes, just a little more . . . now! What a wonderful thing, all those slivers of glass, like an explosion of ice! Large and small pieces that shine on the wood floor and on the carpet, what a wonderful image of destruction, ruin, and perdition! While she picks up the shattered glass, the girl sobs and tries to say something. Yes, make me dizzy with your excuses, you little snake! I can’t throw anything at you; I haven’t the strength to do it. But I can push you under with the weight of my body . . . Like this! Aaah! Help! Help! That is what I wanted, to sink that pink little face into the glass, like this, darling, like this, and may your injuries become infected, and pus take over your face.

For my eighth birthday I was given a new dress, which I had very much wanted. When I tried it on, I didn’t even prick the dress-maker

with the needles, as was my wont. The dress was of sky blue silk, with lace around the décolletage and the cuffs, and I wanted it really tight around the waist. When I tried it on, I held my breath so as to hide my belly. My mother’s waist was as narrow as a wasp’s; all the ladies admired her waist. And I wanted to be like Mama! Oh, and what ribbons adorned my new dress! One on the décolletage, three on the skirt, one in my hair, and all of them as pink as geranium flowers. No, more like tender carnations. That day I barely touched my lunch, I was so anxious to start getting ready for the party, which was to be held in my honor: to have a perfumed bath, to wash my hair, to anoint myself with rose water, and then, when I was finished, to put on that dress. I was ready by five in the afternoon, although the dinner did not begin until eight o’clock. There were three hours until Mama would see me with my new dress. I wore my hair loose, and at that time it reached down to the ground and was as curly as a bunch of eels. I got it into my head that I wanted to look like my mother’s little sister, or a younger friend. I couldn’t stop imagining how she would invite me to preside over the table to show all her guests how proud she was of me, how when the time came to serve drinks she would say to the serving maid:

d’abord

to the little duchess Maria Teresa,

s’il vous plaît

. And the maid would walk right around the long table, past dozens of seated guests, and serve me a little bit of the sweet wine that would pour slowly from the bottle, like a garnet necklace, into the tall wine glass, and dye it the color of blood. I would spend the entire evening sipping that blood like a great lady. When I was dressed and powdered, coiffured and perfumed, I walked

from one end of the house to the other. I went up and down the palace stairs; I contemplated myself in the mirrors on the landings and in the halls; I bowed and curtsied. I had never before worn such a tight-fitting dress. Later, I watched the maids lay the table. Right in the middle, on the pale rose-colored tablecloth, they had arranged a centerpiece of lilacs, which at that time of year were starting to bloom in our garden. It was of the same color as my dress, sky blue, no, lilac blue, and they had decorated it with pink ribbons like those on my dress. My dishes, and mine alone, were decorated with little clusters of lilac.