Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 (81 page)

Read Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974 Online

Authors: James T. Patterson

Tags: #Oxford History of the United States, #Retail, #20th Century, #History, #American History

Carrots, however, failed to move the Freedom party delegates, largely because they offered little. The two delegates to be seated, LBJ said, must include a white and a black, specifically Ed King and Aaron Henry. They were not to be seated as Mississippi delegates—to do so would be to concede the legitimacy of their claim to represent the state—but as delegates "at large." Johnson further sent word that one of the most vociferous Freedom party delegates, Fannie Lou Hamer, should not be permitted to vote at the convention.

Hamer had already attracted extraordinary attention among other delegates and reporters in Atlantic City. An eloquent spokeswoman for what it was like to be black and poor in Mississippi, Hamer was the twentieth child of impoverished, barely literate sharecroppers. In 1962 when she had dared to register to vote, she had been driven off the land where she had worked for eighteen years as a field hand. Later she had been badly beaten for encouraging other blacks to register. She emerged from these ordeals as a strong and uncompromising advocate of equal rights.

74

When she appeared before the credentials committee on August 22, she described in graphic detail to spectators and to television viewers what had happened to her on that occasion:

I was carried to the county jail. . . . And it wasn't long before three white men came to my cell where they had two Negro prisoners. The state highway patrolman ordered the first Negro to take the blackjack. . . . And I laid on my face. The first Negro began to beat, and I was beat until he was exhausted. . . . The state highway patrolman ordered the second Negro to take the blackjack. The second Negro began to beat and I began to work my feet, and the state highway patrolman ordered the first Negro who had beat to set on my feet and keep me from working my feet. I began to scream, and one white man got up and began to beat me on the head and tell me to "hush." One white man—my dress had worked up high—he walked over and pulled my dress down and he pulled my dress back, back up. All of this is on account we want to register, to become first-class citizens, and if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America.

75

When Johnson saw this testimony on TV, he quickly called a presidential press conference in the hope that the networks would cover it and drive Hamer and others off the air. They did as he had anticipated, preempting among others Rita Schwerner, whose husband had been murdered in June. Johnson thought he had silenced "that illiterate woman," as he called Hamer. But the MFDP had the last word, for that evening the networks rebroadcast the hearings in prime-time, including all of Hamer's powerful testimony. Later, when asked to support Johnson's compromise, she snorted, "We didn't come all this way for no two seats." Shortly thereafter the Freedom party delegates decisively rejected the compromise.

In the short run Johnson was the winner of this struggle and the Freedom party loyalists the losers. He was nominated by acclamation, as was Humphrey, his loyal aide. He was convinced, moreover, that most white Americans—most voters—approved of his attempts to avoid identification with extremes. "Right here," he said, "is the reason I'm going to win this thing so big. You ask a voter who classifies himself as a liberal what he thinks I am and he says a liberal. You ask a voter who calls himself a conservative what he thinks I am and he says I'm a conservative. . . . They all think I'm on their side." And that, he said later, was "where the majority of the votes traditionally are."

76

In the long run, however, Johnson's liberal position on civil rights could not satisfy militants at both ends of the spectrum. Given the polarization of emotions concerning race by 1964, this was no longer possible. Angry white delegates from Mississippi raged at his efforts to compromise and walked out of the convention. Some of the Alabamans also stalked out. For them and for many other southerners, Goldwater and Wallace, not Johnson, were the politicians of choice. The electoral results in November confirmed that the majority of white voters in the Deep South remained unreconstructed rebels on the subject of race.

No group was more angry than the MFDP and other civil rights militants. Long suspicious of liberals such as Kennedy and Johnson, they regarded the battle at Atlantic City as the last straw. Many never trusted white people again. Almost all refused to listen to the blandishments, as they saw them, of liberals or governmental bureaucrats. When emissaries of LBJ tried to explain to Hamer that her refusal to compromise might cost Humphrey the vice-presidency, she stared at them in disbelief. "Do you mean to tell me," she asked Humphrey, "that your position is more important to you than four hundred thousand black people's lives?" When Humphrey tried feebly to respond, she walked out in tears. When she ran into him later, she told him, "Senator Humphrey, I been praying about you . . . you're a good man, and you know what's right. The trouble is, you're afraid to do what you know is right."

77

No exchange better captured the gulf that by then was polarizing black militants and white liberals in America.

C

OMPARED TO THE UNREST

in the cities and the turmoil at Atlantic City, the electoral campaign that followed was relatively tame. Goldwater refused to run a demagogic campaign focused on the issue of race. His position, after all, was already well suited to success in the Deep South. Instead, he tried to bring across his highly ideological opposition to Big Government as it had arisen in the United States under the New Deal, the Fair Deal, and the "Dime Store New Deal" of the Eisenhower administration. "Socialism through Welfarism," he maintained, was the greatest threat to Freedom.

78

No presidential candidate in modern American history, however, proved more impolitic. He once told the columnist Joseph Alsop, "You know, I haven't really got a first-class brain." Politically speaking, this seemed evident in the campaign, during which Goldwater went out of his way to offer voters what he called a "choice, not an echo." In the process he issued blunt statements that alienated millions of voters. He went to Appalachia to denounce the war on poverty and to the South to call for the sale to private interests of the Tennessee Valley Authority, which was highly popular in the area. He told the elderly that he wanted to scrap Social Security, and farmers that he opposed high price supports. "My aim," he insisted, "is not to pass laws but to repeal them."

79

Some of his statements were so uncompromising that he opened himself up to ridicule. "The child has no right to an education," he proclaimed. "In most cases he will get along very well without it." American missiles were so good, he said, that "we could lob one into the men's room at the Kremlin." Angry at what he considered the arrogance of the liberal East Coast Establishment, he observed, "Sometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea." Democrats had a field day playing with the motto of his supporters, "In Your Heart You Know He's Right." "In your guts," they quipped, "you know he's nuts."

Goldwater's bellicose statements on foreign policy left him especially vulnerable to criticism. "Our strategy," he said, "must be primarily offensive. . . . We must—ourselves—be prepared to undertake military operations against vulnerable Communist regimes." When asked earlier in the year what he would do about Vietnam, he replied that he would bomb the supply routes in the North. What would he do about trails hidden in the jungle? Goldwater answered that "defoliation of the forests by low-yield atomic weapons could well be done. When you remove the foliage, you remove the cover." Although Goldwater tried to clarify and deny these remarks—he meant tactical weapons, not atomic bombs—he was consistent on one point: let the generals have a free hand, and they would bring victory.

80

If Americans had known what Johnson and his advisers were thinking about Vietnam at that time, Goldwater would not have seemed extreme. For the fighting in Vietnam was going so badly for Diem's forces that administration leaders were developing plans to escalate America's role. By the summer of 1964 they had decided privately that the United States

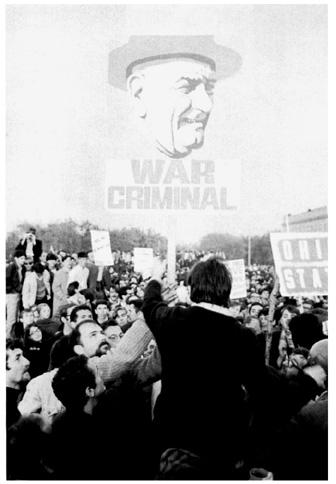

Antiwar protestors, Washington, October 1967.

Library of Congress

.

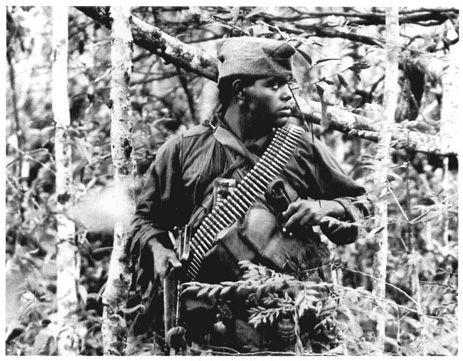

Spec. 4 Ronald Abernathy of Evanston, 111., on patrol in South Vietnam, March 1967.

AP, Library of Congress

.

A wounded GI, in battle of Hue, 1968. Donald McCullin,

Magnum Photos

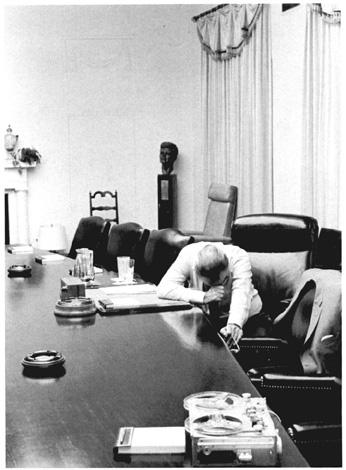

LBJ, July 31, 1968. Jack Knightlinger,

LBJ Library

.

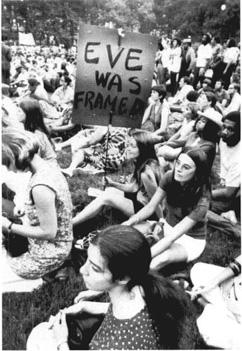

Betty Friedan, 1964.

Library of Congress

.