Grand Opera: The Story of the Met (4 page)

Read Grand Opera: The Story of the Met Online

Authors: Charles Affron,Mirella Jona Affron

With the docking of Manuel Garcia’s troupe on November 7, 1825, well over a half-century before the 1883

Lucia,

Italian opera alighted in New York on the wings of Rossini. It was a time of high civic pride and optimism. Three days earlier, the arrival of the

Seneca Chief,

the first packet boat to make the trip from Buffalo to Albany through the newly completed Erie Canal and then down the Hudson, had been the occasion for a demonstration one hundred thousand strong, the largest yet seen in North America. The canal, waterway to the West, guaranteed the city’s position as the country’s manufacturing, commercial, and financial center. Ambitions to be its cultural capital too had begun to stir. Garcia, a Spanish tenor, composer, and impresario, launched his New World venture on November 29 in Park Row’s Park Theatre with Rossini’s

Il Barbiere di Siviglia

. His Rosina was his seventeen-year-old daughter, mezzo-soprano Maria Garcia, soon to be the legendary Maria Malibran. In attendance on that evening were personalities as disparate as Mozart’s librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte, instrumental in bringing Garcia to New York; Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte, for a time King of Naples and then of Spain, now a resident of New Jersey; and novelist James Fenimore Cooper, whose

The Last of the Mohicans

was soon to be published. Garcia himself sang Count Almaviva, the role he had created in Rome in 1816. During his one New York season, Garcia introduced the city to nine works, among them

Don Giovanni

and four more by Rossini.

12

It would be another seven years before New York built a venue expressly for opera, and it would be twenty-two more and three tries before one such effort, the Academy of Music, would become firmly embedded on the city’s cultural map. However different the three failed enterprises, they had in common the near monopoly of bel canto on their stages. The first, the Italian Opera House, owned and administered by a group of business and civic leaders, was another effort on Da Ponte’s part to bring opera to his adopted country. From the time of Garcia’s visit, Da Ponte had been a vigorous proponent of Italian music and letters, and professor of Italian literature at Columbia College, the first such position in the United States. The Italian Opera House (1833–1835), a small theater located at Leonard and Church streets, opened with Rossini’s

La Gazza ladra

. Nine years later, Palmo’s Opera House (1844–1847), also small, seating only eight hundred, opened on nearby Chambers Street. For a single season it was owned and operated by Ferdinand Palmo, a former restaurateur, who raised his first curtain on Bellini’s

I

Puritani

. Bellini shared the season’s bill evenly with his two bel canto competitors, Rossini, of course, and Donizetti. In contrast to the Italian Opera House and to its immediate successor, the Astor Place Opera House, Palmo’s mission was to bring opera to the people at prices families could afford. But his target audience of immigrants had not swelled to numbers sufficient to support his intentions. For the next two years, a series of directors and companies made doomed attempts to rescue the project. As with the Italian Opera House, Palmo’s small capacity and mediocre casts were the undoing of the balance sheet. On the heels of Palmo’s demise came the Astor Place Opera House (1847–1852), administered, like the Italian Opera House, by wealthy patrons.

New York had taken sharp financial, social, and demographic turns between the passing of the Italian Opera House in 1835 and the christening of the opera house on Astor Place in 1847. The accompanying cultural turn was animated by the inauguration of steamship service between Bristol and New York in 1837; it had increased and quickened transatlantic itineraries for goods and persons, including singers and instrumentalists. The establishment of the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York in 1842, still the oldest orchestra in the United States, had begun to shape the musical taste of the city’s population. The new opera house had pursued the affluent to 8th Street and Broadway, a neighborhood undergoing upscale development. And although bel canto continued to hold sway over the repertoire, the opening night

Ernani

bore witness to the advance of Giuseppe Verdi. The problems of the eighteen-hundred-seat house were obvious from the beginning: disappointing subscription rolls and ticket sales, unexceptional casts. The fatal blow was the Astor Place riot of 1849, the bloodiest episode in New York theater history. On May 10, armed with stones, nativists in support of the American actor Edwin Forrest, who was playing Macbeth at the Bowery Theatre, laid siege to the theater on Astor Place, where the English actor Charles Macready was performing, he too as Macbeth. The militia, called to reinforce the police, fired into the crowd. Before it was over, the dead numbered around twenty-five—no one could say for sure. Tangential to opera, at least on the surface, the riot raged in front of the opulent edifice built by the establishment largely for its own gratification. More importantly for our discussion, the issues that provoked the carnage were also central to debates about the place of opera, if any, in the American democratic order. On one side stood the old guard, determined to defend the patrician signs of their European origins. On the other stood the nativists, joined by fiercely anti-English Irish

immigrants for whom opera represented a foreign, aristocratic tradition incompatible with their republican slogans.

13

It took three decades for Italian opera to plant lasting roots in New York, the span that separated Garcia’s visit from the 1854 inception of the Academy of Music, the last of the Metropolitan’s antecedents. In the interim, various incongruous factions were on the attack: “populists who disdained aristocratic pretense in Americans, intellectuals who mistrusted music’s power over people, moralists for whom a foreign-language genre could not contribute to theatrical reform, romantic conservatives who wanted to hold onto the ‘palmy days’ of the legitimate stage, and self-proclaimed outsiders who disparaged the wealth and social prestige that attendance at the opera was seen to represent.”

14

Led by German-born banker August Belmont, the subscribers of the Academy of Music made an appeasing gesture in the direction of “populists” and “self-proclaimed outsiders” by attaching “academy” to the name of the impressive new building six blocks north of Astor Place, thereby underscoring the institution’s didactic mission: the promotion of American composers, the training of American performers, and the musical education of the people. Moreover, the enormous initial capacity of the hall, pegged by the press at four thousand and greater (rebuilt after an 1866 fire, it shrank by more than half), was cited as prima facie evidence of the will to accommodate the vast spectatorship of the polis. But high-minded social purposes went largely ignored. Critics focused instead on the miserable sight lines, lighting, and ventilation; while the rich were framed to flattering effect by the extreme pitch of the tiers and the elegance of the setting, fully half the seats, primarily those at prices as low as $.25, offered scant, if any, visibility of the stage.

15

On the Academy’s first night, October 2, 1854, the New York debuts of two undisputed international stars, Giulia Grisi and Giovanni Mario, crowned what was already an event of significance to New York’s standing. The three-month-long inaugural Grisi-Mario season began with

Norma

and continued with works by the bel canto composers exclusively. Grisi had created the role of Adalgisa in Bellini’s opera, as well as those of Elvira in

I Puritani

and Norina in Donizetti’s

Don Pasquale;

Mario was widely touted as the greatest tenor of his generation. The magical resonance of their names is captured by Henry James who, as a boy, lived with his family a stone’s throw from the nascent Academy: “when our air thrilled, in the sense that our attentive parents reechoed, with the visit of the great Grisi and the great Mario, and I seemed, though the art of advertisement [James refers to the

theater’s billboard] was then comparatively so young and so chaste, to see our personal acquaintance, as he could almost be called [Monsieur Dubreuil, a

comprimario,

a singer of secondary roles], thickly sandwiched between them. Such was one’s strange sense for the connections of things that they drew out the halls of Ferrero [a nearby dancing school] till these too seemed fairly to resound with Norma and Lucrezia Borgia, as if opening straight upon the stage, and Europe, by the stroke, had come to us in such force that we had but to enjoy it on the spot.”

16

Grisi and Mario had sailed in the wake of the fabled Jenny Lind and Marietta Alboni, lured to New York by generous fees. In the years to come, the Academy’s sponsors leased the theater to a series of managers, some for only a season, others returning to try again. Bel canto programs were peppered with the first American performances, soon after their European premieres, of Verdi’s

Rigoletto, La Traviata,

and

Il Trovatore,

Meyerbeer’s

L’Africaine,

and Gounod’s

Roméo et Juliette

. On February 20, 1861, on his way to his inauguration, Abraham Lincoln’s stop in New York included an Academy performance of Verdi’s

Un Ballo in maschera;

the President-elect left before act 3 and was thereby spared the onstage spectacle of a ruler’s assassination. Less than two months later, on April 12, Fort Sumter would be attacked and the American Civil War would begin. New York would soon enjoy the boom that led to its recognition as a magnet for capital. By the 1880s, the city was no longer a cultural backwater where fading singers could succeed on the strength of a European reputation. A discerning and exigent musical press was ready and able to point out in expert detail a performer’s technical weaknesses, faulty intonation, and stylistic vulgarities. The public had evolved as well. In 1850, P.T. Barnum had created frenzy for Jenny Lind with concerts largely devoted to timeworn melodies; thirty years later, Adelina Patti, the acknowledged “Queen of Song,” undisputed star of Europe’s opera stages, returned to the United States after a two-decade absence, prepared to feed her public a diet of ballads. “But it was another America to which Patti came. It was an America which had half outgrown the Italian opera, and which listened with delight to the music of the future . . . [a] cultivated, intelligent, musically developed America.” On November 8, 1880, to take one spectacular but by no means unique example, Gerster sang

La Traviata

at the Academy, Campanini was at Steinway Hall, a block or so away on 14th Street, and, at Booth’s Theatre on 23rd Street, Sarah Bernhardt was making her US debut in the Scribe-Legouvé melodrama

Adrienne Lecouvreur

.

17

By 1878, the year Colonel Mapleson took over at the Academy, society had again moved northward. Fourteenth Street was no longer the fanciest address in town. Millionaires had marched their mansions up Fifth Avenue, the Astors to 34th Street, the Vanderbilts to 52nd, the Roosevelts to the corner of 57th. The Metropolitan had followed in the footsteps of its stockholders. If the opening round of the opera war was a dustup between the “Old Families” and the “Newcomers,” as soon as the Nobs and the Swells were amicably ensconced in their fauteuils (some had boxes in both houses), a second battle was engaged, on another ground, the stage, and with other contestants, the stars. Sopranos, in particular, would vie night after night on boards little more than a mile apart. The managements had no choice but to compete in ways they knew would perforce end in the ruin of one or the other of their companies. In fact, it ruined both. Mapleson was at an initial disadvantage. He had lost some of his best-known artists to offers from Abbey that could not be refused. But, he held two trump cards, Gerster and Patti. Early on, the

[Dramatic] Mirror

(Oct. 27) predicted, adopting the inescapable military metaphor, that the Academy would emerge victorious as long as Mapleson would keep “on giving such eminently satisfactory performances as that which opened his campaign.” But sometimes even Patti could not fill more than two-thirds of the auditorium; on Gerster nights, the theater was two-thirds empty. Patti’s fee, the highest of any singer in the world, could simply not be amortized. And what is more, her grip on the company, not to mention on the public’s attention, rankled Gerster and put the mediocrity of other colleagues in unflattering relief. The quality of the Met’s ensemble was decidedly higher and its new sets and costumes beyond the Academy’s reach. Still, Abbey was faced with his own problems. Best estimates put the cost of the Met’s principal singers, comprimarios, orchestra, chorus, and the rest just shy of $7,000 per performance; revenues fell far short of expenses. If Mapleson’s season closed deeply in the red, it also closed in glory: Patti trilled in duet with Sofia Scalchi, who had wandered downtown at the expiration of her Met contract. They, and Rossini, and

Semiramide

filled every seat and “all available standing room” (

Herald,

April 25).

18

Each company had presented a fall and spring season of nineteen operas (Abbey added a twentieth for Philadelphia alone); nearly half the titles were identical, for the most part bel canto and early Verdi works. The titles exclusive to Mapleson were Rossini’s

La Gazza ladra

and

Semiramide,

Donizetti’s

Linda di Chamounix

and

L’Elisir d’amore,

Bellini’s

Norma,

the Ricci brothers’

Crispino e la comare,

and Verdi’s

Ernani

. With the exception of

Aïda

and

Roméo et Juliette,

none of the Academy’s offerings was thought of as modern. The contrasting profile of the Met emerged from relatively recent French works, along with

Lohengrin,

Arrigo Boito’s 1868

Mefistofele,

and the first US performance of Amilcare Ponchielli’s

La Gioconda,

premiered at La Scala in 1876. Abbey, unlike Mapleson, was bent on demonstrating that his “Grand Italian Opera” was alert to the public’s predilection for Wagner and for contemporary fare.

Lohengrin

showed off the company to marked advantage, and although sung in Italian, of course, this edition of Wagner prompted Krehbiel to make the case for Abbey’s more inclusive policy. A passionate Wagnerite, he cited the audience’s patience as proof “that the patrons of the opera in New York are ripe for something better and nobler than the sweetmeats of the hurdy-gurdy repertory, and that a winning card to play in the game now going on between the rival managers would be a list, not necessarily large, of the best works of the German and French schools”

(Tribune). Mefistofele

and

La Gioconda

were, for the most part, well performed. By all accounts, Campanini and Nilsson sang Boito’s Faust and Margherita to far better effect than they had when impersonating the same characters in Gounod’s version on opening night. Krehbiel chose to take issue with the opera itself, “the novelty of Boito’s conception having worn off”; he now found it “bizarre . . . inane, insipid, when it is not positively vulgar in style”

(Tribune)

. Despite the misfire of its act 2 explosion, the premiere of Ponchielli’s sumptuously staged

La Gioconda

elicited lengthy and mostly positive reactions. Henderson, who thought it “among the most important art occurrences of the season,” placed the composer in “a sort of half-way ground between Verdi’s latest manner and the moderate productions of Wagner,” his score, though unoriginal, containing “much that is beautiful and impressive.” While Henderson judged Nilsson ill cast in a role intended for dramatic soprano, Krehbiel reported that she “kept the audience in a state of almost painful excitement by the vivid manner to which she depicted the sufferings of the street singer”

(Tribune)

. He was harsher on Ponchielli than his colleague, charging the composer with resorting to “the old style.” The two magisterial critics agreed that the enterprise did credit to the fledgling company by offering “grand opera in a style worthy of the metropolis”

(Tribune)

.

Performed in Abbey’s new raiments, some of the “old style” operas made strong impressions. On the third night of the season,

Il Trovatore

introduced

Roberto Stagno. The tenor thrilled the audience with his long-held high B at the end of “Di quella pira.” The Azucena of Zelia Trebelli “was a triumph of high vocal art worthy of being ranked with Madame Sembrich’s brilliant performance on Wednesday”

(Tribune)

. On hearing the Leonora of Alwina Valleria, the Met’s first American-born diva, the

Tribune

declared, “there can be no ‘off night’ at the Metropolitan so long as she relieves either Madame Nilsson or Madame Sembrich”

(Tribune)

. Soprano Emmy Fursch-Madi had glowing notices for her Alice in Meyerbeer’s

Robert le diable

. Fursch-Madi was also compelling as Ortrud to Nilsson’s Elsa and as Donna Anna in a

Don Giovanni

that flaunted Nilsson as Donna Elvira and Sembrich as Zerlina. Abbey’s Met had its fair share of disappointing evenings as well, many occasioned by the weak contingent of male singers. Stagno soon found that his reliable high notes did not suffice to trigger favorable reviews for his Don Ottavio

(Don Giovanni),

Jean de Leyde

(Le Prophète),

Lionel

(Martha),

and Enzo

(La Gioconda)

. Italian baritone Luigi Guadagnini was trounced as Rigoletto: “It is a thousand pities that the poor man came so far to do so little”

(Times)

. In an underprepared

Mignon,

Nilsson was judged to have fallen short of her own more youthful and graceful performance of thirteen years earlier, when she had introduced Ambroise Thomas’s portrait of Goethe’s touching waif to America. Trebelli’s Carmen compared unfavorably to Minnie Hauk’s, New York’s first, in 1878. Thomas’s take on

Hamlet

was denounced as lèse-Shakespeare in its solitary New York hearing. With the exception of Nilsson, Campanini, and Scalchi, the principals of

Les Huguenots

were “simply earnest, correct, and lifeless” and the orchestra “almost continuously irresponsive to Signor Vianesi’s baton”

(Times)

.

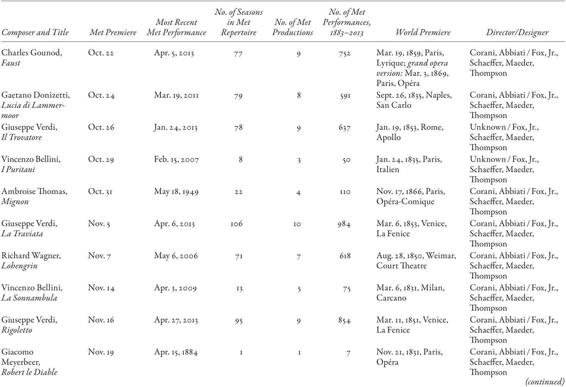

TABLE 1.

The Metropolitan's Inaugural Season, 1883–84

(all operas given in Italian)

TABLE 1.

(continued)