Greenglass House (34 page)

Authors: Kate Milford

“I'll try, I guess.” But he was pretty sure he wouldn't have much success.

Â

twelve

For the rest of that day, it was very, very hard not to stare at Mr. Vinge. Milo couldn't figure out how his parents managed it either.

First, they tried to get Fenster out of the house and away to safety on the Belowground Transit System. He and Brandon and Mr. Pine bundled up on the pretense of double-checking that their fixes to the generator were still holding and disappeared into the snow, but instead of going around the house, Milo saw them hike uphill toward the woods and the hidden entrance to the BTS. Half an hour later all three were back again, looking more like icicles than men. Milo was standing next to his mother in the kitchen, waiting for a cup of hot chocolate, so he heard Mr. Pine's whispered explanation. “Control system's frozen solid and there's some damage. Brandon thinks he can fix it, but not quickly.”

“Damage?” Mrs. Pine repeated warily. “Damage like the generator damage?” By

like the generator damage

Milo was pretty sure she meant

sabotage.

“Not sure. I mean, he doesn't think so, thank goodness. If it is, someone did a way more convincing job this time around.”

For the rest of the day, while Brandon came and went, Milo's parents made sure one of them was always in the same room as either Mr. Vinge or Fenster. They didn't tell Fenster who they thought the agent was, which was probably a good idea. Fenster would never have been able to keep it together if he'd known. He'd have stared, for sure. As it was, he was acting more and more paranoid as the day progressed.

Christmas Eve day wore on toward Christmas Eve night, and despite all the excitement in Greenglass House, it proceeded just as slowly as it seemed to every year. The snow kept on and the wind kept whipping it into the corners of windows, and now and then Milo forgot about Mr. Vinge and Fenster and even Negret and fell dreamily into thinking of frosted windowpanes and silver bells. The smells of baking ham and pies and bubbling cranberry sauce with orange drifted through the first floor to mingle with the pine and bayberry and peppermint scents of the candles. And just as the light outside began to dim, Milo's father came down the stairs with three patchwork stockings with bells on their toes.

Mr. Pine hung the stockings from their customary hooks on the mantelpiece, then turned to Milo, who was curled up with his book in the loveseat by the window. “You know what we haven't done? Any sledding. What do you say we get out of here for a bit, just you and me? I bet with all the ice under the snow it'll be perfect sledding out there. If we hurry, we can probably get an hour in before full dark.”

They suited up and headed out into the whistling cold, making their way carefully down the porch steps. Then Milo followed his father toward the section of woods where all the outbuildings were. They walked in their usual companionable quiet, except when Mr. Pine hummed occasional bits of “Up on the Housetop.” It was Christmas Eve, it was snowing, the lights of home were glowing behind him, and Milo was going sledding with his dad.

The structure they called the garage had never actually held a vehicle. Milo's dad regularly vowed that one of these days he'd clean it out so they could finally put a car in there, but Milo doubted he'd ever get to it. It was the largest and closest of all the outbuildings, a big square of red brick with two wooden doors, which stood just inside the trees. Mr. Pine had taken the shovel from the porch, and now he dug away the drifts piled against the front of the building. Then he brushed the snow from the latch, and together they managed to shove the left-hand door open just far enough to squeeze through and get inside.

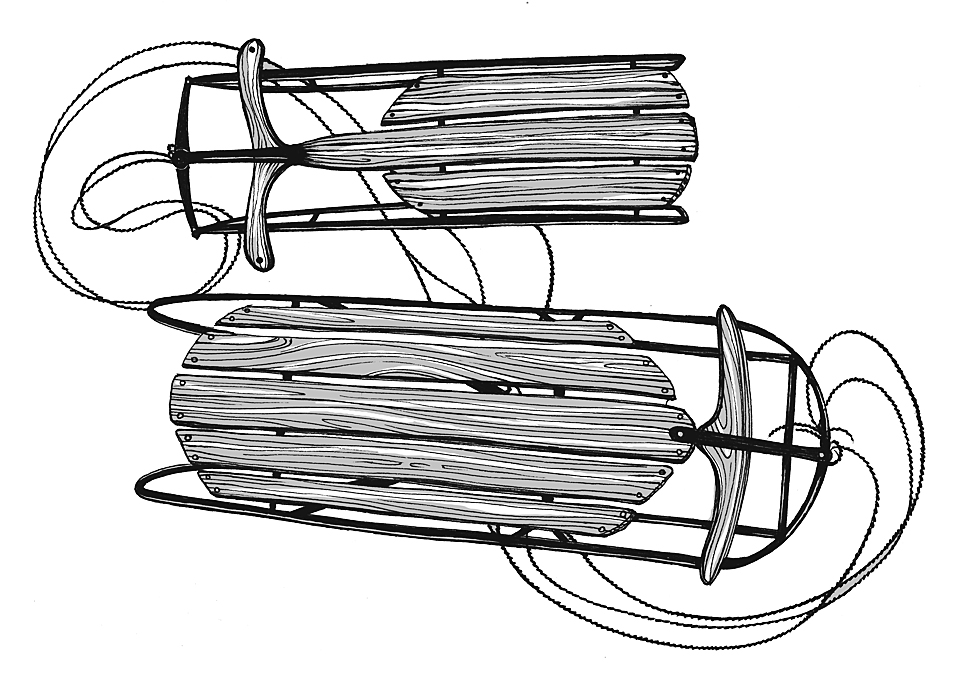

A pop and a sizzle, and a bulb very much like the ones in the Emporium fizzled to life overhead. “The sleds are in here somewhere,” Mr. Pine said, surveying the space. “Where'd we put them last year?”

“Probably under everything,” Milo grumbled. “We keep saying we need a place for them, but we never find one.”

“This year, then. Without fail. You search that side and I'll take this one.”

Milo picked his way along the right-hand side of the space while his father started down the opposite side. The sleds would be easy to spot, Milo figured, and he wasn't disappointed. One of them turned up right away, up on top of a pile near the back. The green metal rails and polished wood stuck out like a sore thumb among the rest of the junk, which was mostly lumber and stuff that fell into the broad category of

parts:

an old engine, several drawers that didn't seem to have furniture to go with them, sections of picket fencing that had once been painted yellow, that sort of thing.

“Found one, Dad.” Milo tugged on the front of the sled, but the back half wouldn't budge, and he wasn't tall enough to see what was holding it fast. “Stuck, though.”

“The other one's over here. Hang on.” A moment later Mr. Pine appeared and climbed onto a heavy old headboard. As he yanked the sled free, the headboard shifted under his weight and the whole pile lurched. Mr. Pine leaped down, fumbling the sled in his arms. It fell, bouncing off something metal with a

ploing.

“Darn,” he grumbled, examining the runners. “Chipped the enamel.”

Milo ignored him. He bent for a look at the thing the sled had banged and did a double take. It was mostly hidden under the headboard. “Dad, can you help me lift this?”

“What for?”

“I want to see the thing that's under it.”

Mr. Pine shrugged but did as he was asked, and together they managed to lift the headboard just enough. And there it was, rusted and twisted and with several bits of ancient dead ivy clinging to it here and there: the very same gate Milo had been seeing images of everywhere he looked for the last three days. Half of it, anyway. Clem's antique dealer had at least been telling the truth about where his half had come from.

He reached out to touch it where several flakes of green enamel from the sled's runners clung. It was smaller than he'd expected somehow: just about his own height. He'd assumed all the pictures were showing the kind of gate that was the size of a door, something at least as tall as an adult. But this was like a small garden gate, the kind you might lean on to talk to your postman as he passed on the sidewalk. Nonetheless, it was the same one. It had to be. There was even a hook for a lantern just where the stitched gate on Mrs. Hereward's bag had its little knot of golden yarn.

“Milo,” Mr. Pine grunted. “Gotta let go of this now. Heavy.”

“Dad,” Milo said when Mr. Pine had lowered the headboard again, “where's that gate from?”

“Don't know. It's like the attic and the basementâhalf the stuff in here is from before your mom's and my time. Why?”

“It's the gate in our windows. Each one in the stairwell has that gate on it somewhere. Haven't you ever noticed it?”

Mr. Pine frowned. “I think you'll have to show me later.”

“Yeah, I will.” Maybe it wasn't so surprising that his father hadn't noticed the gate hidden in the stained glass before. Milo hadn't noticed it either, not until he'd seen the watermark on Georgie's map.

Found the gate, found the gate,

he sang silently as he and his father hiked along, each trailing a sled behind him. Who knew what it meant, or if it meant anything at all, but still, he was delighted. It was a piece of the house's history, which meant it was a piece of Milo's history, and every bit he managed to collect was precious.

The place they were headed was only a little ways from the building that hid the entrance to the Sanctuary Cliff Belowground Transit System stop, so they went first to check on Brandon's progress on the train repairs. Then they tramped on to the sledding spot, a slope of clear, unblemished white.

Mr. Pine was right; the icy snow was perfect. He shoveled some into a barrier at the bottom of the hill so they wouldn't go barreling into a tree; then they hiked up and raced down and overturned their sleds on the barrier-snowdrift and did it all again and again until the light was gone from the sky. Then Mr. Pine took a pair of flashlights from one of his pockets for the walk home.

They left the sleds and the shovel on the porch and trooped inside, red-faced and snow-covered and grinning. “Have a nice time?” Mrs. Pine asked, waiting with a steaming mug in each hand while they fought their way out of their coats and boots.

Mr. Pine kissed her cheek. “Just what the doctor ordered. Am I right, Milo?”

“Yup.” He took his mug and inhaled. The hot chocolate had a sharp peppermint bite to it, and there was whipped cream on topâthe homemade kind that had to be dolloped on with a spoon and took longer to melt.

“Everything's stable, but the train's still down and Brandon's called it a night,” Milo's mom said quietly to his father. “And there was an answer from the ferry dock, just after you two left. If I read the signals right, they're shut down but looking for somebody to come out. I couldn't put a reply together before dark, though. Just about an hour to dinner,” she added, louder.

Milo crept back into the cave behind the tree with his mug. He leaned against the wall, put his feet up on one of the larger presents, and took a sip of hot chocolate. The fire was crackling away, the house was as calm as it had been in days, and even Fenster (visible through the branches if Milo leaned just a bit to his left) seemed to have settled down. He and Lizzie and Brandon and Georgie were playing some kind of card gameâgirls against boys, by the look of it. Dr. Gowervine must've been out on the porch smoking again; there was just the faintest scent of pipe tobacco in the room. And Mr. Vinge didn't appear to have moved the entire time Milo and his father had been gone.

The rucksack was still under the tree where Milo had left it when he'd rushed out to tell his parents what he suspected about Mr. Vinge. He opened it up, took out

The Raconteur's Commonplace Book,

and flipped to the story Mr. Vinge had mentioned earlier.

I've never yet found anyone who could tell me how the two things came to be associated with each other

,

a quiet young man named Sullivan was saying,

but for as long as any oldster on the Skidwrack can remember, superstitious folk have always crossed themselves when they see river otters, for fear of the Seiche. Except, of course, for the odd foolish romantic who actually thinks he wants to meet one. The Seiche are supposed to be beautiful, after

all.

“Hey.” Meddy crept into the tree-cave.

Milo closed the book reluctantly. “Where've you been?”

“I don't know, upstairs? Were you looking for me?”

“Not really,” Milo admitted. He'd sort of fallen under the spell of Christmas Eve and had been enjoying having some time to himself. It hadn't even occurred to him to wonder what Meddy had been up to, despite his discovery on the sledding trip (which, he thought guiltily, he should probably have invited her to join). “But listen! I found the other half of the gate!”

“The gate?

Our

gate? Where?”

“Out in the building we use for storage. I found it buried under some stuff at the back. Dad says it's probably from before he and Mom took over the place, just like Clem said, but he doesn't know anything about it. It's smaller than I thought. Do you think it means anything?”

Meddy looked up as a rush of cold air spiked through the room. Clem and Owen must've gone for a walk, and were just now returning, all smiles and pink cheeks. “No idea,” she said, “but it's neat that it's there.”

Â

Mrs. Caraway's voice rang out from the kitchen. “Dinner, folks!”

“Guess I'll take the living room again.” Milo tucked

The Raconteur's Commonplace Book

into his rucksack, slung the bag over his shoulder, and crept out from behind the tree with Meddy on his heels. The card players sitting on the floor around the coffee table were still at their game. “Who's winning?” he asked.

“Who do you think?” Georgie replied with enough relish that Milo suspected it was the girls.

Meddy liked to get her food last in order to observe everybody, so she held back, and Milo and Dr. Gowervine were the first to the table.

“Was anything missing from your bag?” Milo asked him as he picked up a plate from the stack.

“Hmm? Oh, no, nothing. It's so strange,” he said. “Why on earth do you think anyone would go to the trouble of stealing notes on such an obscure thing?”

“Don't know.” But certainly the thief was interested in

plenty

of obscure things. Milo was pretty sure it was what those things had in commonâGreenglass House itselfâthat the thief was really intent upon.

That

Mr. Vinge

was intent upon, he corrected himself silently. That the

customs agency

was intent upon. Was he just after as much information about the house and its history as possible, trying to figure out its connections to smuggling? Or was there something more?