Griefwork (16 page)

Authors: James Hamilton-Paterson

‘And what then?’ drawled the Italian chargé, fitting a cigarette into his oval holder somewhere inside the gardener’s brain. ‘A different work of art, that’s all. An exquisite garden like this is a little landscape, and a landscape is

constructed,

put together

with wit, sensibility and artifice for aesthetic and symbolic ends. “Nature”, on the other hand, is brainlessly aleatory. Look how randomly she plonks trees down in just – I do beg your pardon,’ as Leon’s leathery hand reached out for his prize. ‘Would you, I wonder, be making a collection of these?’

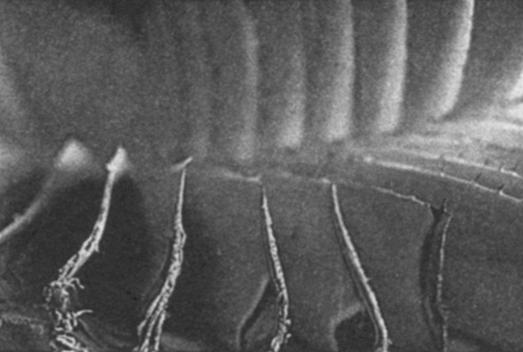

But Leon didn’t want a different garden, he wanted the same one. Nor did he want a newer or improved Palm House. The instant he had first set foot in it as little more than a boy he had recognised that it was tuned. That was the word. He had once overheard a night visitor describe how one could make the most perfect facsimile of a Stradivarius violin but that a good musician could always tell from its sound it was not the genuine article. It didn’t matter how carefully one chose wood from the very grove Stradivarius had used, or analysed the chemistry of the varnish and reproduced it exactly, or even strung it with gut from descendants of the sheep which had supplied its original. The tone would always be different. Apparently it had to do with changes taking place in the entire fabric of the instrument in response to two or more centuries of constant playing. Infinitesimal molecules of wood lined themselves up like iron filings around a magnet’s prongs … something like that, anyway. But tuning was the image which most exactly described how the Palm House felt. All that carefully tended growth over the years had somehow harmonised the whole structure. It had all bedded down just right and the glass let through exactly the right quantities of the correct rays and the weathercock’s shadow traced the right path.

He blew out the candles in his slow ritual and paused by the

Utotia

mirifica

that dim Bettrice woman had so disliked. She must have a nose of iron, he thought, sipping at a bloom. ‘Anaesthetic’, indeed. It was like taking a gulp of genever and saying it tasted drunk-making instead of holding it on the tongue and breathing out, letting it slide down a bit and breathing out

some more, a whole palette of subtle taste shades distinguishing themselves one by one. Of this pale flower she had snorted up its vertiginous purple but had missed the vanilla and chypre and the elusive breeze of brisk green energy. On impulse he did something so rare for him he could almost hear the House fill with gasps of astonishment. He picked the bloom and, having completed his round, approached the slight dark figure meekly outlined in the doorway of No Admittance.

‘No change, my Felix, no change,’ he said, presenting the flower.

The young man took it and held it to his nose, head bowed. It was quite impossible to tell from his posture whether it was merely demure or else an expression of profound sadness.

‘No end,’ said Leon. ‘Rely on me, no end.’

These are terrible words for any young man to hear, particularly when he has been agonisingly ransomed from what had previously seemed like a possible life. After all, what did it mean to be rescued? What had been restored? (The dark puddle at the foot of the wall gleamed for a moment like a sea separating rescuer from victim, the victim from his previous self.) Thereafter his life would begin again shakily on a barren, unknown island which he might or might not decide to inhabit, an indecision which could prolong itself to the grave.

It could only be guessed how much Leon had told Felix as he talked him through shock and pain and delirium, hour after hour, though the boy had surely been in no fit state to remember tales of another’s life when his own was at the brink of dissolution. On the other hand he may have attained that point so easily reached drifting in or out of sleep when the entire fiction of one’s life thins to a thread which can become entwined with almost any other version and seem no less real. Thus the voices from a bedside wireless may entangle themselves in a waking dream, for stories have

an affinity for one another and merge at the least opportunity. Each day marks fresh hours of effort to keep pure and clear the life story one has inherited from yesterday. Does this not explain our monstrous preoccupation with courtroom dramas, so often pawky and sordid? As we watch the accused racking their brains for the right narrative braid, the right yarn which will lead away from guilt and towards acquittal we acknowledge our own wrestlings with alternative identities, which given half a chance (such as panic) so readily anneal themselves into a life we have never had but which everyone else seems to recognise as our own – an alchemy which quickly turns braid to hemp. It was hardly likely that Felix’s life before that fateful day had resembled the gardener’s; the man was surely too anomalous and singular. But supposing the boy’s rescue and convalescence had plaited into his history new, overheard strands which were not wholly alien? An orphan, then? Sooner or later almost everyone becomes an orphan. An aching loss? Most people nurse one of those, too.

Perhaps after all Leon had talked unheedingly, staring not at the bruised, slit-eyed face or seeping moss pad but at one corner of the mattress or a spot on the wall, talking maybe to the unseen audience of plants. And maybe the gypsy, hollowed into an echoing shell by pain and creeping knowledge, had rung with his words until they began to describe himself. And there again perhaps Leon had really been addressing a bronchial child gasping for breath in a cottage hospital bed who, by sleight of circumstance, now lay on a blood-soaked mattress in a boiler room.

No

change.

What faith was being kept, then, locked into repetition?

No

end.

Could Felix sense himself being dissolved, his own loss and pain hijacked by a stranger to blend into his? And had his language been stolen too, as he lay on the floor watching tongues of flame? Stolen and given over to shrubbery, maybe, so that his saviour-captor would ever afterwards listen

more attentively to mere plants than to him? The injustice of falling victim is exceeded only by the assertion of rescuer’s rights. The injured’s desire for amends, for compensation, is swamped by the healer’s expectation of reward. Money? Nothing so crude. Just boundless love, and a bemused obligation to fall in with a stranger’s fantasies. So what must it have been to come up on one elbow on a mattress stiff with your own blood and feel yourself falling into that harsh mouth bent solicitously above you? Mouth? A face, body, an entire being, full of a desire which can never be kissed away. For the moment is long past when the right kiss at the right time might have freed this terrible fond man.

Now, in times of unease, with his own night people shedding rumours of change like a sinister perfume, the gardener could only issue blank denials. They might take the form of an impassioned speech in the Palm House’s defence (not yet delivered but gradually being honed and refined before his leafy and attentive audience) or of a single flower plucked and presented to a baffled youth in earnest of some ancient covenant the boy had never signed. Passive and windguided he might have been, this gardener, and weakly skewed with loss; but what impassioned resolve had it taken to construct an entirely private life in the heart of a public garden? Was such a man suddenly to relax his grip, as rotten putty releases a cascade of glass? A survivor, then, drawn to another, even if by a love too implacable to be called affection, or by an affection too voracious to qualify as love. Long ago this survivor was himself a boy, who had stood in fishy dungarees with his pale hair flailing a cheek, nearly invisible among vast gestures of land and sea and sky. Then, he had affirmed a new pact with an inseparable companion to whom he had already sworn his lifetime oath and with whom he daily walked, ate, slept and talked: that whatever happened and wherever he went he would never rely on anyone else.

Twenty years later he simply said ‘My Felix’ and, a protective arm about the thin shoulders, steered a mute gypsy holding a flower towards a boiler room in a postwar city.

Utotia mirifica,

the

flower

which

Leon

had

picked,

was

remark

ably

philosophical

about

its

own

beheading:

‘One of the lotuses – who has since gone to shed her light in what’s probably a quite dingy diplomatic apartment – used to say she tried to cultivate a spirit of constant astonishment. This, she’d been told, was the correct attitude for facing the world. She was right, wrong only in thinking it needed cultivating. Tonight constant astonishment came to me of its own accord and won’t leave for a little yet. To have one’s neck deliberately broken by one’s own gardener is a shock, and although not actually painful has left me with a feeling which goes beyond pain: that of the most desolating separation, of being literally torn away from one’s parents without so much as a farewell. My brothers and sisters were coming into bud even as I bloomed and it’ll now be up to them to be “exotic and druggy”, as one of the night visitors described me.

‘Now that the original shock has diminished I’m beginning to feel honoured. To be singled out as a special gift is flattering, even if it means an early death. It’s true I might have lived another week or so had I not been picked: a week of wasting

precious pollen grains in powdering a succession of huge, blind, white, oily noses shoved violently in among my stamens. Then the noses would have switched their attention to my unfolding siblings and a day or two later I should have been dead-headed. So it would come to the same thing in any case. But if I lose a few days by having been chosen in this amazing way I gain immeasurably from being caught up in the economy of homage.

‘The

economy

of homage? But I’m not sure what else to call it. At its simplest homage is a unilateral act – of acknowledgement as much as of love, of obedience no less than praise. So the gardener picked the flower which he himself had planned, sown and raised, and presented me to his damaged vagrant in an act of homage. But it goes beyond that. It has to include a constant sense of … of astonishment, really, that the gardener too is humble before his plants, and we before our gardener. “There ought to be someone to thank” is a feeling I’ve never been without even though I know perfectly well there’s nothing to thank except contingency which, in the absence of anything else, comes to seem suspiciously divine. Being snapped off at the neck as part of a transaction which expresses this feels, as I say, like an honour. The gypsy was touched by the gesture: I could feel it by the way he held me and put me in a jam-jar of water in the centre of the table in No Admittance.

‘The more I think about it the easier it becomes to read an unintended accuracy into that phrase “exotic and druggy”. These, too, are people who are going to die, and even if they never expect to glance up and see a slow drift of angels eddying among the wrought-iron something of that knowledge can leak out of them in their most casual asides. Exotic has to mean more than just coming from outside or outlandish, else familiarity would reduce everything to the humdrum. Yet this doesn’t happen in the Palm House any more than it happens with the greatest art. No matter what taxonomies are used to tame us, to

hold us in the direct line of scientific sight so its beady glare can focus and refocus on whatever of our attributes has a passing interest, we’re never quite there again, are never precisely the same. What could be more hackneyed than a rose? But what more elusive, since it never stales for long?

‘So a conclusion is forced upon us, very simple, very hard to accept: that everything is exotic and eventually incomprehensible. Our gardener is almost alone in perceiving this. None of the others do: not Anselmus, nor Witte, nor Seneschal, nor the motley assistants. One of the few visitors to have more than a glimmering is that Italian chargé, of course, but it makes him uneasy and he has to hide it beneath effete badinage. But our gardener knows; and no matter that the tamarind at the far end of the House refers to him as a sort of failed priest acting out a displaced love, it’s still a form of homage. Personally I don’t agree with that interpretation, which strikes me as facile and modish (the tamarind’s still young, of course). Our gardener’s a horticulturist through and through. Yet undoubtedly he feels the mystery and in his muddled, wilful way knows nothing can diminish it – that it alone merits the attention of a constant intelligence. He’s sad to fail so often. Sad? It’s his greatest remorse. Sometimes he suspects he has held Cou Min’s shadow tiny in the centre of each pupil in order to block his sight. It’s safer to gaze at the past casting its lovely shadows than to contemplate the present, and certainly the future. He knows it’s an evasion. But what counts for him is the homage. To what, though? To whom?

‘And so I’m expiring fragrantly but not unhappily in my glass jar of water, caressed by the gypsy’s gaze as he squats by the table and lowers his chin on to folded hands a mere eighteen inches away. There’s great pain in his eyes and every so often they flood slightly as though he would weep if only men and gypsies were allowed to. I can do nothing for him except be the

gardener’s gift and exhale astonishment steadily into his face in the hopes that he will catch it too. This is the astonishment which the visitor called “druggy” because she had expected something familiar, sweet and safe – a tropical rose, perhaps. But my scent unnerves. It wasn’t designed for you, gypsy, pretty lad; but if you pay it heed even as I pay you homage you might learn things.