Growing Up Brady: I Was a Teenage Greg, Special Collector's Edition (25 page)

Read Growing Up Brady: I Was a Teenage Greg, Special Collector's Edition Online

Authors: Barry Williams;Chris Kreski

"I said, `I think you're going to be a disturbance. If you're standing around watching the shooting, and everybody knows you

don't want to be in it, I think that's gonna bother people, especially the kids. I think you should go.'

"At which point he stared me down and, very slowly, very deliberately, said, `I'm not going anywhere, and I have every intention

of staying through this thing.' So Bob stayed on the set, scowling.

"Anyway, Paramount found out about the situation and called

me, asking if they should send over a couple of security guards to

cart Bob away. `Over my dead body!' I told 'em. `There's absolutely

no way I'm going to allow those kids to see their father yanked

away bodily.'

"So then they asked me, `What are you gonna do about him?'

and I said, 'If he doesn't bother anybody, and stays out of everybody's way, nothing.' They still wanted to haul him away, but I

wouldn't allow it. That would have been awful."

So that's how we shot the episode. Every day Bob would show

up, stand off in a corner, and scowl. At the same time, Sherwood

would show up, sit in his office, and do a slow burn. Bob was now

officially on borrowed time. In fact, if "The Brady Bunch" had sur vived for a sixth season, we would have definitely been fatherless.

Yep, while Robert Reed stood grumbling in a corner, Sherwood

Schwartz was quietly sitting in his office, smiling, and plotting Mike

Brady's murder. Sherwood told me that had we gone into another

season, by the time we filmed our first episode, Mike would have

died, off camera (probably in a car wreck)-or at the very least, he

would have been sent away on an extended architectural project,

never to return.

Robert Reed's Original Memo Regarding Episode 116

"The Hair-Brained Scheme" Segment of "The Brady Bunch"

To Sherwood Schwartz at al.

Notes: Robert Reed

There is a fundamental difference in the theatre between:

1. Melodrama

2. Drama

3. Comedy

"... this is for you

Sherwood!"

(Courtesy Sherwood

Schwartz)

4. Farce

5. Slapstick

6. Satire &

7. Fantasy

They require not only a difference in terms of construction, but

also in presentation and, most explicitly, styles of acting. Their

dramatis personae are noninterchangeable. For example, Hamlet,

archtypical of the dramatic character, could not be written into

Midsummer Night's Dream and still retain his identity. Ophelia

could not play a scene with Titania; Richard II could not be found

in Twelfth Night. In other words, a character indigenous to one

style of the theatre cannot function in any of the other styles.

Obviously, the precept holds true for any period. Andy Hardy could

not suddenly appear in Citizen Kane, or even closer in style, Andy

Hardy could not appear in a Laurel and Hardy film. Andy Hardy is a

"comedic" character, Laurel and Hardy are of the purest slapstick. The boundaries are rigid, and within the confines of one theatrical piece the style must remain constant.

Why? It is a long since proven theorem in the theatre that an

audience will adjust its suspension of belief to the degree that

the opening of the presentation leads them. When a curtain rises

on two French maids in a farce set discussing the peccadilloes of

their master, the audience is now set for an evening of theatre in

a certain style, and are prepared to accept having excluded certain levels of reality. And that is the prime difference in the styles

of theatre, both for the actor and the writer-the degree of reality

inherent. Pure drama and comedy are closest to core realism,

slapstick and fantasy the farthest removed. It is also part of that

theorem that one cannot change styles midstream. How often do

we read damning critical reviews of, let's say, a drama in which a

character has "hammed" or in stricter terms become melodramatic. How often have we criticized the "mumble and scratch"

approach to Shakespearean melodrama, because ultra-realism is

out of place when another style is required. And yet, any of these

attacks could draw plaudits when played in the appropriate

genre.

Television falls under exactly the same principle. What the networks in their oversimplification call "sitcoms" actually are quite

diverse styles except where bastardized by careless writing or

performing. For instance:

"M*A*S*H" ... comedy

"The Paul Lynde Show" ... Farce

"Beverly Hillbillies" ... Slapstick

"Batman" ... Satire

"I Dream of Jeannie" ... Fantasy

And the same rules hold just as true. Imagine a scene in

"M*A*S*H" in which Arthur Hill appears playing his "Owen

Marshall" role, or Archie Bunker suddenly landing on "Gilligan's

Island," or Dom DeLuise and his mother in "Mannix." Of course,

any of these actors could play in any of these series in different

roles predicated on the appropriate style of acting. But the maxim

implicit in all this is: when the first-act curtain rises on a comedy,

the second-act curtain has to rise on the same thing, with the

actors playing in commensurate styles.

If it isn't already clear, not only does the audience accept a

certain level of belief, but so must the actor in order to function at

all. His consciousness opens like an iris to allow the proper

amount of reality into his acting subtext. And all the actors in the

same piece must deal with the same level, or the audience will not

know to whom to adjust and will most often empathize with the

character with the most credibility-total reality eliciting the most

complete empathic response. Example: We are in the operating

room in "M*A*S*H," with the usual pan shot across a myriad of

operating tables filled with surgical teams at work. The leads are

sweating away at their work, and at the same time engaged in

banter with the head nurse. Suddenly, the doors fly open and

Batman appears! Now the scene cannot go on. The "M*A*S*H"

characters, dealing with their own level of quasi-comic reality,

having subtext pertinent to the scene, cannot accept as real in

their own terms this other character. Oh yes, they could make fast

adjustments. He is a deranged member of some battle-fatigued

platoon and somehow came upon a Batman suit. But the Batman

character cannot then play his intended character true to his own

series. Even if it were possible to mix both styles, it would have to

be dealt with by the characters, not just abruptly accepted.

Meanwhile, the audience will stick with that level of reality to

which they have been introduced, and unless the added character

quickly adjusts, will reject him.

The most generic problem to date in "The Brady Bunch" has

been this almost constant scripted inner transposition of styles.

1. A pie-throwing sequence tacked unceremoniously onto the end

of a weak script.

2. The youngest daughter in a matter of a few unexplained hours

managing to look and dance like Shirley Temple.

3. The middle boy happening to run into a look-alike in the halls of

his school, with so exact a resemblance he fools his parents.

And the list goes on.

Once again, we are infused with the slapstick. The oldest boy's

hair turns bright orange in a twinkling of the writer's eye, having

been doused with a non-FDA-approved hair tonic. (Why any boy of

Bobby's age, or any age, would be investing in something as outmoded and unidentifiable as "hair tonic" remains to be explained.

As any kid on the show could tell the writer, the old hair-tonic routine is right out of "Our Gang." Let's face it, we're long since past

the "little dab'II do ya" era.)

Without belaboring the inequities of the script, which are varied and numerous, the major point to all this is: Once an actor has

geared himself to play a given style with its prescribed level of

belief, he cannot react to or accept within the same confines of

the piece, a different style.

When the kid's hair turns red, it is Batman in the operating

room.

I can't play it.

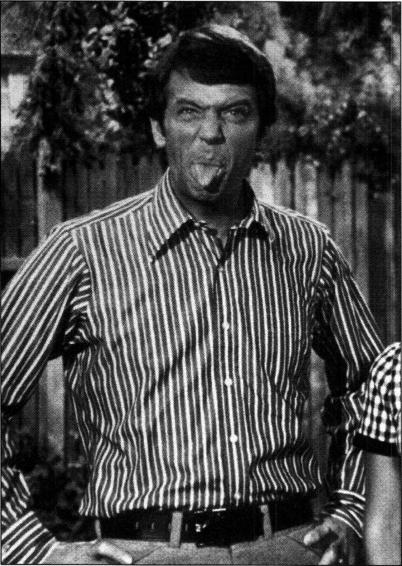

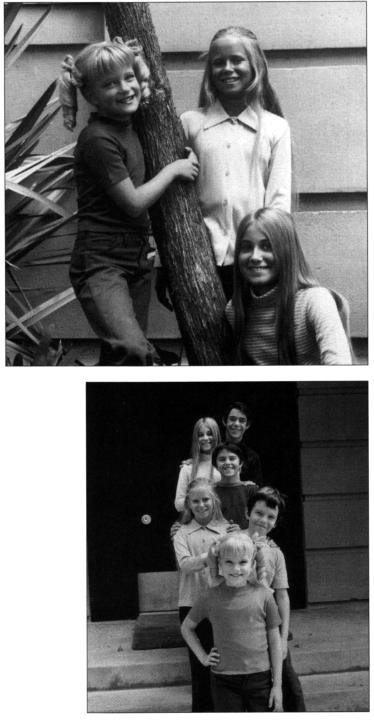

Posing for publicity shots. (Courtesy Sherwood Schwartz)

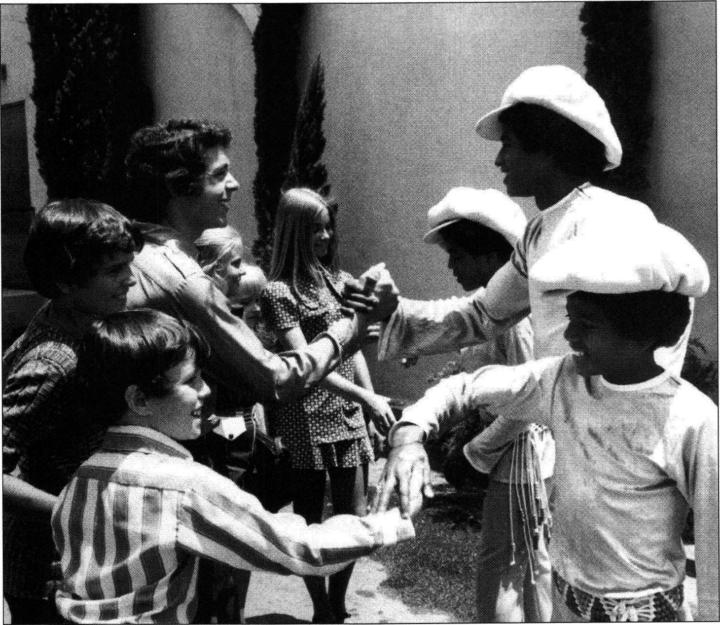

Brady 6 meets Jackson 5. Michael Jackson is in the foreground shaking hands with Michael

Lookinland. ((D 1991 Capital Cities/ABC, Inc.)

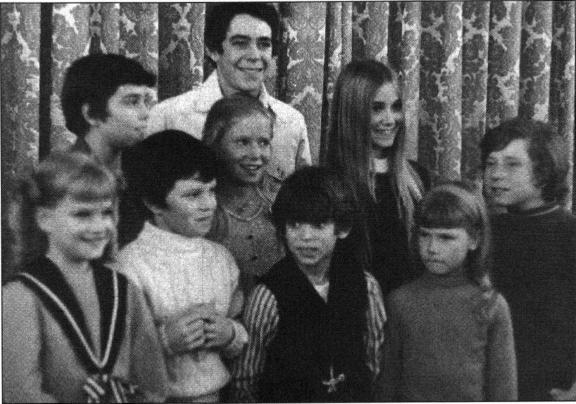

Bradys meet

Partridges.

((D Karen

Lipscomb)

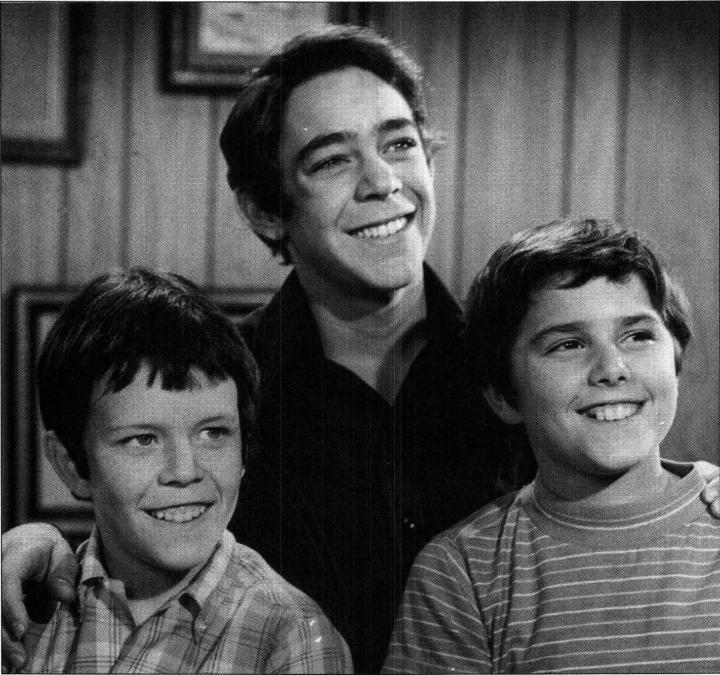

No cavities here. (Courtesy Sherwood Schwartz)

Posing for

publicity

shots.

(Courtesy

Sherwood

Schwartz)