Grunts (6 page)

The battle, like most, was not an organized, precise effort. It degenerated into a ragged contest of small groups, on-the-spot leadership, and physical probabilities. The caves were the main battlegrounds. Squad-sized groups of Marines, sometimes assisted by tanks, assaulted the caves. Flamethrower men took the lead. Stinking of fumes, bending under the weight of their cumbersome fuel tanks, they edged up to caves and torched them with two-second bursts. Nearly every cave had to be taken or sealed because, when outflanked, the Japanese would not retreat to their own lines. Instead they would stubbornly stay in place and fire on the Americans from the rear.

For the infantry, the day dragged on (at least for those lucky enough to survive), melting into one assault after another. Nothing could be taken without the foot troops taking the lead, yet often they could make little headway without tank support. The 3rd Marines took the cliff about midday, but they remained under intense enemy fire. In just one typical instance, mortar fire killed six men and wounded two others in Corporal Gilhooly’s squad. A few hours later, the regiment took Adelup Point, following an intensive barrage by destroyers, rocket ships, and tanks. Resupply was now a problem since it was very difficult to haul crates of ammo, food, and water cans up the cliff. Any movement on flatter ground provoked enemy fire. Ingenious Marines rigged up cables to and from the cliff, in order to move supplies and wounded men. For a longer-term solution, engineers and Navy construction battalions (Seabees), with the help of bulldozers, scooped out a road at the tip of the cliff, all the while under fire. By the time the sun set on that horrible July 21, the 3rd Marine Division and 1st Provisional Marine Brigade had carved out shallow beachheads, none more than a few hundred yards deep. The 3rd Marine Division alone had suffered 105 killed in action, 536 wounded, and 56 missing in action. With every passing hour, though, the Americans grew stronger as reinforcements and supplies came ashore, all protected under the watchful gaze of a powerful, unopposed fleet.

13

The Japanese planned to crush this lodgment before it could grow any larger. From the beginning, their intention was to defend Guam at the waterline, counterattack immediately with all-out banzai charges, and repel the invasion. Like Germany’s Erwin Rommel, who had opposed the Normandy invasion the previous month, the Japanese at Guam believed that the Americans were at their most vulnerable during the invasion itself. If allowed to come ashore in large numbers and build up their awesome array of firepower and logistical capability, they would inevitably prevail. Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo, and Lieutenant General Takeshi Takashina, the Japanese commander at Guam, believed that “victory could be gained by early, and decisive, counterattacks.” For two years, since Guadalcanal, this had been the Japanese approach: defend at the waterline, counterattack, and overwhelm the Americans with all-out banzai attacks that epitomized the Japanese fighting spirit (

yamato-damashii

), and thus Japanese superiority. Guam was the classic case of this offensive mentality. “Counterattacks would be carried out in the direction of the ocean to crush and annihilate [the Americans] while [they] had not yet secured a foothold ashore,” Lieutenant Colonel Takeda later wrote.

14

On the evening of July 21-22, the Japanese began a series of such disjointed attacks against the American beachheads. Most of the attacks consisted of infiltration by individual Japanese soldiers or groups of a dozen, twenty, or thirty. This followed the tableau of the Pacific War. At night the Japanese liked to sneak into American “lines,” which were usually nothing more than perimeters of loosely organized foxholes. “They come to you,” one Marine commented, “especially at night. They infiltrate very well.” The Japanese attempted to crawl close to the holes, surprise the occupants, and kill them at close range. Through long experience, the Americans knew to expect such frightening personal assaults. Men slept in shifts or in fits and starts. By and large, anyone moving at night outside of their holes was fair game. Navy ships assisted the ground troops by illuminating the area with star shells, bathing the landscape in undulating half-light all night long. “These would light up several hundred feet overhead, and slowly drift downward providing a light bright enough to detect anyone moving near you,” Private Welch recalled.

Most of the Japanese activity on this night consisted of these sorts of terrifying but small-scale encounters. The exception was the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade sector, where Colonel Tsunetaro Suenaga, commander of the 38th Infantry Regiment, ordered a full-scale attack, with General Takashina’s permission, to eliminate the American Agat beachhead. What is truly revealing is that both officers knew the attack would probably fail to annihilate the American beachhead, and would likely destroy the remaining combat power of the 38th. Yet they still decided, with little debate or caution, to do it. In this sense, they were facing a logical consequence of the decision Takashina and his superiors in Tokyo made to resist the American invasion at the waterline and push them into the sea with immediate counterattacks. They had designed their defenses, and deployed their soldiers, with this in mind. Now, with the successful American landing, they felt their best option was to carry out their original plan. But there was something else at work here. So powerful was the self-sacrificial suicide

yamato-damashii

cult among Japanese officers on Guam that such an attack seemed the only proper course of action. In so doing, they were, in effect, putting their heads in a collective noose and even fastening that noose in place.

That night, when the order filtered down the ranks, the Japanese soldiers took the news with sadness and stoicism. They were good soldiers who followed orders. Beyond that, though, they were products of a culture that placed a high value on meaningful gestures, personal sacrifice, and eternal honor. Some of the men cried. Most burned letters and mementos from home. The men of one battalion ate a last meal of rice and salmon, washed down with liberal quantities of sake. Colonel Suenaga burned the colors of his regiment lest they fall into enemy hands.

At around midnight on July 22, they unleashed a volley of mortar and machine-gun fire while the lead troops, screaming at the top of their lungs, rushed forward in waves, crashing into the American frontline foxholes. “The Japs came over, throwing demolition charges and small land mines like hand grenades,” one Marine infantryman remembered. “Six Marines were bayoneted in their foxholes.” The Americans opened up with machine guns, rifles, grenades, and mortars. Fighting raged back and forth for control of Hill 40, a prominent patch of high ground that overlooked the beach. In the eerie half-light, combat was elemental, often man-to-man, the sort of vulgar struggle that permanently scarred men’s minds with the awful memories of intimate killing.

One key to the American stand was artillery. Since about midday, many batteries of the 12th Marines and the 40th Pack Howitzer Battalion had been in place, firing in support of the infantry. Now, in the middle of the night, the gun crews responded to fire mission requests, even though their positions were under attack. “Our battery fired between 800 and 1,000 rounds of ammunition that night,” Lieutenant P. A. Rheney of the 40th recalled. In one gun pit, Captain Ben Read, the battalion’s executive officer, spotted four shadowy figures following a line of communication wire. He challenged them and they rolled away, whispering in Japanese. A gunnery sergeant in an adjacent hole threw a grenade, killing one Japanese. Rifle fire killed the other three. “By about 0130, we were up to our necks in fire missions and infiltrating Japs,” Read wrote. “Every so often, I had to call a section out for a short time so it could take care of the intruders with carbines and then I would send it back into action again [firing their howitzers].” In another gun pit, Private First Class Johnnie Rierson saw four enemy soldiers, exposed by the light of a flare, edging toward his position. He and another Marine opened fire with their carbines. “We killed one, but another one was only wounded. He kept trying to toss grenades into our gun pit before he died, but they hit a pile of dirt. That saved us.” They later found two bodies a few yards away.

Night attacks are always among the most difficult of operations, even under the best of conditions, and for the Japanese, these were hardly the best of conditions. The Japanese attack quickly degenerated into a confused melee, with small fanatical groups wandering around, looking for trouble, then getting cut down by American firepower, particularly machine guns. In one instance, a Japanese soldier was silhouetted against a ridge, fully visible under the light of a flare, yelling at the Marines: “One, two, three, you can’t hit me!” The Americans riddled him with a hail of rifle bullets. Elsewhere, Colonel Suenaga, brandishing a sword, was leading his men. He got hit by mortar fragments, staggering him. A rifle bullet finished him off. He went down in a lifeless heap.

The most serious threat to the U.S. Agat beachhead was an enemy tank-infantry attack on the Harmon Road in the 4th Marine Regiment sector. The Marines could hear “the elemental noise of motors and guns and tank treads grinding limestone shale. Banzai screams pierced the flare-lit night.” There were four light tanks, with thin armor and small guns (so small they were derided as “tankettes” by the Americans). Private First Class Bruno Oribiletti destroyed two of the tanks with bazooka fire before he himself was killed. A platoon of Sherman tanks, augmented by howitzer fire from Captain Read’s battalion, blew up the other tanks. Most of the Japanese infantrymen around the tanks fought to the death. By dawn, after a furious night of fighting, Colonel Suenaga’s attack was over. The 38th Infantry had practically ceased to exist. Japanese bodies were lying everywhere, rotting in the rising sun. Captain Read found a dozen corpses near his gun pit. “The dead Japs did not have weapons, but were loaded with demolitions and grenades.” They had intended to blow up the howitzers. Staff Sergeant O’Neill of the 22nd Marines also counted twelve enemy bodies near his position. “All night, the Japanese [had] probed our lines, first one place, then another.” The American beachhead remained secure. All Colonel Suenaga had succeeded in accomplishing, besides his own demise, was weakening the Japanese ability to defend against American efforts to break out of the Agat beachhead. Dismal failure or not, the pattern was set. The Japanese on Guam now chose to succeed or fail with such counterattacks.

15

Fright Night

The evening of July 25 was rainy and tense. For several days, the Americans had advanced incrementally, launching costly daylight attacks, enduring nighttime infiltrators and small banzai assaults. The two American beachheads still had not joined hands. Neither of them was any more than a couple miles deep. Casualties were piling up. Infantrymen dug shallow foxholes along ridgelines or any other high ground they could find. Frontline positions consisted of various holes, each one about three feet deep (at best), spaced several yards apart, with two or three men in each hole. Mortars and artillery pieces were in gun pits a few hundred yards behind the forward holes. In the 3rd Marine Division’s beachhead, medics had set up a field hospital in a draw, just inland from the beach. Support troops were having a difficult time resupplying the frontline fighters because of bad weather, challenging terrain, and Japanese mortar and artillery fire. Guam was shaping up as a slow, bloody slog.

The Japanese were also hurting. Day by day the Americans were grinding them down with their relentless attacks and firepower. General Takashina had lost about 70 percent of his combat troops, along with many of his commanders. His units were immobilized during the day by pervasive American air strikes and naval barrages. By July 25, he believed that his men would not be able to stand the mental strain of the American attacks much longer. Takashina felt that, at this rate, he and his men were simply waiting for inevitable defeat and death. In the words of one of his officers, the general felt that “some effective measure was urgently needed.”

For Takashina, that effective measure meant an attack.

Yamato-damashii

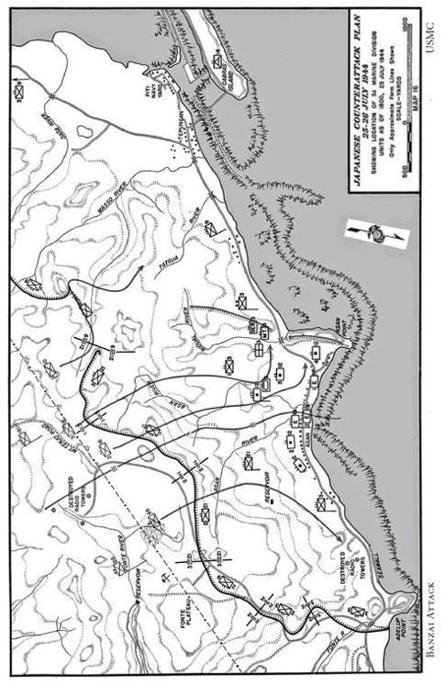

demanded aggressiveness, not passive defense. Takashina felt that the American lodgment was still vulnerable. He must eliminate it before the Americans had time to land more troops, more vehicles, and permanently entrench themselves with their incredible ability to build roads, organize their ground forces, and employ superior technology. He made up his mind to gather his remaining strength and launch an all-out effort to push the Americans into the sea. Although this would be a nighttime banzai attack, it would not merely be a mindless suicidal gesture. Takashina planned to amass the remnants of his 18th Infantry Regiment, along with the 48th Mixed Brigade, and hurl them at the 21st Marines while exploiting the gaps that existed between the positions of the 21st and its neighboring regiments. Having breached the American lines, Takashina’s stalwarts would then savage the American rear areas, thus extinguishing the Asan beachhead. Meanwhile, at Agat, the 38th Infantry’s survivors, many of whom were bottled up on the Orote Peninsula, were to fight their way out and inflict devastating losses on the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade. The plan was a long shot, based on audacity and verve. It was the ultimate example of the prevailing Japanese notion that American invasions could only be defeated at the waterline by overwhelming, self-sacrificial counterattacks.