Guantánamo Diary

Authors: Mohamedou Ould Slahi,Larry Siems

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Autobiography & Memoirs

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions■hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Mohamedou would like to dedicate his writing to the memory of his late mother, Maryem Mint El Wadia, and he would also like to express that if it weren’t for Nancy Hollander and her colleagues Theresa Duncan and Linda Moreno, he couldn’t be making that dedication.

| January 2000 | After spending twelve years studying, living, and working overseas, primarily in Germany and briefly in Canada, Mohamedou Ould Slahi decides to return to his home country of Mauritania. En route, he is detained twice at the behest of the United States—first by Senegalese police and then by Mauritanian authorities—and questioned by American FBI agents in connection with the so-called Millennium Plot to bomb LAX. Concluding that there is no basis to believe he was involved in the plot, authorities release him on February 19, 2000. |

| 2000–fall 2001 | Mohamedou lives with his family and works as an electrical engineer in Nouakchott, Mauritania. |

| September 29, 2001 | Mohamedou is detained and held for two weeks by Mauritanian authorities and again questioned by FBI agents about the Millennium Plot. He is again released, with Mauritanian authorities publicly affirming his innocence. |

| November 20, 2001 | Mauritanian police come to Mohamedou’s home and ask him to accompany them for further questioning. He voluntarily complies, driving his own car to the police station. |

| November 28, 2001 | A CIA rendition plane transports Mohamedou from Mauritania to a prison in Amman, Jordan, where he is interrogated for seven and a half months by Jordanian intelligence services. |

| July 19, 2002 | Another CIA rendition plane retrieves Mohamedou from Amman; he is stripped, blindfolded, diapered, shackled, and flown to the U.S. military’s Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. The events recounted in Guantánamo Diary begin with this scene. |

| August 4, 2002 | After two weeks of interrogation in Bagram, Mohamedou is bundled onto a military transport with thirty-four other prisoners and flown to Guantánamo. The group arrives and is processed into the facility on August 5, 2002. |

| 2003–2004 | U.S. military interrogators subject Mohamedou to a “special interrogation plan” that is personally approved by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. Mohamedou’s torture includes months of extreme isolation; a litany of physical, psychological, and sexual humiliations; death threats; threats to his family; and a mock kidnapping and rendition. |

| March 3, 2005 | Mohamedou handwrites his petition for a writ of habeas corpus. |

| Summer 2005 | Mohamedou handwrites the 466 pages that would become this book in his segregation cell in Guantánamo. |

| June 12, 2008 | The U.S. Supreme Court rules 5–4 in Boumediene v. Bush that Guantánamo detainees have a right to challenge their detention through habeas corpus. |

| August–December 2009 | U.S. District Court Judge James Robertson hears Mohamedou’s habeas corpus petition. |

| March 22, 2010 | Judge Robertson grants Mohamedou’s habeas corpus petition and orders his release. |

| March 26, 2010 | The Obama administration files a notice of appeal. |

| November 5, 2010 | The DC Circuit Court of Appeals sends Mohamedou’s habeas corpus case back to U.S. district court for rehearing. That case is still pending. |

| Present | Mohamedou remains in Guantánamo, in the same cell where many of the events recounted in this book took place. |

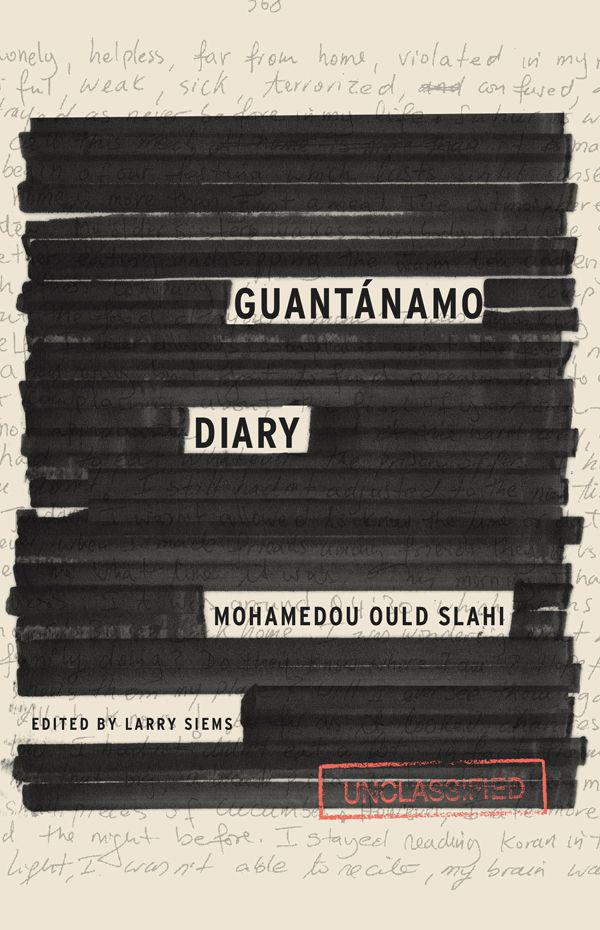

This book is an edited version of the 466-page manuscript Mohamedou Ould Slahi wrote by hand in his Guantánamo prison cell in the summer and fall of 2005. It has been edited twice: first by the United States government, which added more than 2,500 black-bar redactions censoring Mohamedou’s text, and then by me. Mohamedou was not able to participate in, or respond to, either one of these edits.

He has, however, always hoped that his manuscript would reach the reading public—it is addressed directly to us, and to American readers in particular—and he has explicitly authorized this publication in its edited form, with the understanding and expressed wish that the editorial process be carried out in a way that faithfully conveys the content and fulfills the promise of the original. He entrusted me to do this work, and that is what I have tried to do in preparing this manuscript for print.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi wrote his memoir in English, his fourth language and a language he acquired largely in U.S. custody, as he describes, often amusingly, throughout the book. This is both a significant act and a remarkable achievement in itself. It is also a choice that creates or contributes to some of the work’s most important literary effects. By my count, he deploys a vocabulary of under seven thousand words—a lexicon about the size of the one that powers the Homeric epics. He

does so in ways that sometimes echo those epics, as when he repeats formulaic phrases for recurrent phenomena and events. And he does so, like the creators of the epics, in ways that manage to deliver an enormous range of action and emotion. In the editing process, I have tried above all to preserve this feel and honor this accomplishment.

At the same time, the manuscript that Mohamedou managed to compose in his cell in 2005 is an incomplete and at times fragmentary draft. In some sections the prose feels more polished, and in some the handwriting looks smaller and more precise, both suggesting possible previous drafts; elsewhere the writing has more of a first-draft sprawl and urgency. There are significant variations in narrative approach, with less linear storytelling in the sections recounting the most recent events—as one would expect, given the intensity of the events and proximity of the characters he is describing. Even the overall shape of the work is unresolved, with a series of flashbacks to events that precede the central narrative appended at the end.

In approaching these challenges, like every editor seeking to satisfy every author’s expectation that mistakes and distractions will be minimized and voice and vision sharpened, I have edited the manuscript on two levels. Line by line, this has mostly meant regularizing verb tenses, word order, and a few awkward locutions, and occasionally, for clarity’s sake, consolidating or reordering text. I have also incorporated the appended flashbacks within the main narrative and streamlined the manuscript as a whole, a process that brought a work that was in the neighborhood of 122,000 words to just under 100,000 in this version. These editorial decisions were mine, and I can only hope they would meet with Mohamedou’s approval.

Throughout this process, I was confronted with a set of challenges specifically connected with the manuscript’s previous

editing process: the government’s redactions. These redactions are changes that have been imposed on the text by the same government that continues to control the author’s fate and has used secrecy as an essential tool of that control for more than thirteen years. As such, the black bars on the page serve as vivid visual reminders of the author’s ongoing situation. At the same time, deliberately or not, the redactions often serve to impede the sense of narrative, blur the contours of characters, and obscure the open, approachable tone of the author’s voice.

Because it depends on close reading, any process of editing a censored text will involve some effort to see past the black bars and erasures. The annotations that appear at the bottom of the page throughout the text are a kind of record of that effort.

These notes represent speculations that arose in connection with the redactions, based on the context in which the redactions appear, information that appears elsewhere in the manuscript, and what is now a wealth of publicly available sources about Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s ordeal and about the incidents and events he chronicles here. Those sources include declassified government documents obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests and litigation, news reports and the published work of a number of writers and investigative journalists, and extensive Justice Department and U.S. Senate investigations.

I have not attempted in these annotations to reconstruct the original redacted text or to uncover classified material. Rather, I have tried my best to present information that most plausibly corresponds to the redactions when that information is a matter of public record or evident from a careful reading of the manuscript, and when I believe it is important for the overall readability and impact of the text. If there are any errors in these speculations, the fault is entirely mine. None of Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s attorneys holding security clearances has reviewed

these introductory materials or the footnotes, contributed to them in any way, or confirmed or denied my speculations contained in them. Nor has anyone else with access to the unredacted manuscript reviewed these introductory materials or the footnotes, contributed to them in any way, or confirmed or denied my speculations contained in them.

So many of the editing challenges associated with bringing this remarkable work to print result directly from the fact that the U.S. government continues to hold the work’s author, with no satisfactory explanation to date, under a censorship regime that prevents him from participating in the editorial process. I look forward to the day when Mohamedou Ould Slahi is free and we can read this work in its entirety, as he would have it published. Meanwhile I hope this version has managed to capture the accomplishment of the original, even as it reminds us, on almost every page, of how much we have yet to see.