Gutshot (14 page)

Authors: Amelia Gray

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Literary, #Psychological

“You certainly are doing just fine.”

It took me a few hours after she was gone to calm down, but I eventually decided that her happiness, though fleeting and confused, and alienated from the love and comfort of others, is still happiness, and I should be glad and grateful. Her old raffia beach bag had sprinkled stray gravel when she lifted it to go and I saw enough of it studding the rug to ruin the vacuum.

I’ve earned the right to sit after years on my feet. I started in my teen years as a cashier at the sporting goods store, feeling the blood struggle to work its circuit back up my system. It was more of the same at the chalkboard, incanting grammatical clauses, ankles swollen so thick that they looked ready to give birth to a pair of screaming children that would match the ones I served. Whole afternoons were lost tracing the edge of the road from home to school and from school back home, shivering against the trucks, toddling in stupid shoes that inspired knots, my flask warm all the while against my thigh. I leaned like a pack beast against walls and doorframes, waiting for the day to end. I stood beside my man at the altar, stood to save our child from the fire, and stood to hold her while she fussed and puked, whispering in her ear that the sitter was stealing from us. Sleep was a horizontal version of the same; I braced my feet against a pillow, standing in my dreams. And so, yes, when the work was over and with it the requirement of mobility, I sat immediately and with satisfaction. I wore out folding chairs and sofa cushions and then I found my velveteen rose, my reinless ride, and I did take my throne and fuse its plush to my own and from it for the remainder of my days I will Ride.

Angela returned the next morning, refilled the tub for my feet, and fed me pieces of ham. When I was through, she wiped up the mess of magazines and soiled clothing, working without complaint. I was suspicious.

“Would you like a ride to the early meeting?” she asked.

“That would be so kind.”

“I value you truly.”

“And I you, darling.” We were a mother and daughter in a stage play. I took her wrists, which limped in my grasp. She twitched and she made a chuffing sound. I thought she was angry with me, but she was gentle with my tubes as she loaded me into the car.

At meeting, the young man who had caught me before smiled and sat on the far end of the room. I waited patiently until it was my time to share.

“My child should be grateful for the life she has been afforded through my sacrifice and work,” I said. “She should be thankful for my loving control, optimistic for the years ahead. There are cultures in which the daughter is tied to the mother for her entire adult life, physically bound with a rope, released only for the carnal act, and then the two are bound together again. You’ll find a maternal lineage of women going through the streets like that, and when one slows to observe a basket of peaches, they all stop and make a group decision on the merits of the greengrocer. Compared to that, we seem so distant as to be almost strangers.”

A young woman applauded, laughing. I pitied her, forced to dry out in a lonesome apartment, opening tinned food for cats, slicing a peach for her own dinner and eating it over a sink facing the wall. She makes much of her own bravery but has no one to be brave for, and when she dies, her old cat will pluck out her eye. She will be found by a landlord collecting his rent.

At night I think of my child above me, my husband above her, and my old smiling Higher Power above them both, and I say:

Keep this girl hidden out of the light so that her eyes may become wide dark voids that might better reflect me.

Angela came bearing a box of doughnuts and handed me one on a plate. A fly had been troubling my legs all morning and this was a happy departure. She talked of a memorable television program, digging into her bag as she went on, the snapped straw at its corners ripping her stockings when it grazed her leg. Her lovely dark hair was matted and her right knee was roseate with a blooming bruise. The contents of her bag threatened to emerge: a pilled sweater; three or four notebooks; disposable chopsticks in their paper; the parched nub of a carrot. Surely there was a wallet in there, some identification, her old first-aid card. A package of gum, stale and somehow rumpled. She extracted a fork and set it on my plate as the fly landed on the doughnut, plunging its sucker mouth.

“Eat your breakfast,” she said, glancing up from her bag for only a moment. The skin around her eyes was cracked at the edges like she was carved from clay. I would keep her under glass if I could. She found a dried mass of facial tissue, honked into it, and examined the evidence. The fly rubbed its spindled legs together and placed them on the doughnut, a chocolate-frosted variety.

“I wish you would ride with me to my lover,” she said.

I took a healthy bite. The fly tried valiantly to extract itself from where it was trapped, and the ticklish sensation inside my mouth started me laughing. “Where?” I asked.

She regarded my laughter. “Not too far.”

That damn fly invigorated me.

“In the woods,” she said.

“All right then, before I change my mind.”

She clasped her hands and kissed me on the cheek. If I had been able to reach the picture of her father on the mantel, I would have turned it to face the wall.

* * *

This drive would be longer, she said, and we needed to prepare. It took some time in the car to wedge the spare tank under my legs, and once we figured that out, the glove compartment popped open and wagged against my belly. She drove us to the edge of town, past the county school and the new junkyard, a handful of ranches, the regional airport, and the place where the community college took their cadaver dogs out to train them.

She spun the wheel a couple of minutes after we passed the old junkyard and we jagged off the road onto a gravel path. She shifted into a lower gear as we bounced over the road, which transitioned to dirt in short order. My body groaned with the jostling and I gripped the dash.

She had to keep up a pace fast enough that we wouldn’t sink. A colorful series of pennants were strung up, the kind from a party store, and she turned there and pressed on. I wondered at how she got out here in the first place. The glove compartment unlatched again on a significant bump and out spilled cassette tapes and receipts and a travel guide to Oklahoma.

“You are going to destroy your alignment,” I murmured to the mess.

At that moment she stopped the car so violently I thought that she was angry with me, then she ran us into a log and took out the engine entirely. But then she put it in park and trotted around to let me out. “Come on,” she said.

We were parked at the unceremonious end of a trail, foliage on three of four sides. She had taken us as far as we could go. Another bright line of flags was strung across a low branch. The pennants read

CONGRATULATION

, the

S

tied around the tree. She headed for the woods but turned back before she rounded the bend. “Come on,” she repeated.

My shirt rode up when I leaned against the exterior of the car, and the moisture condensed below my shirt and soaked through the elastic edge of my pants and onto the broad plain of their jersey fabric.

“How far is it?”

“We came all this way. Just over the ridge.”

Walking was an insult to my condition. This was my only child, knowing the pain I was in and forcing me to go pursue that pain for some silent third party. This was the first time we had been at this impasse, and my heart sank at the idea that it would not be the last. Still, I obeyed. My ankles moaned against the intrusion of unstable ground, but I obeyed. The terrain soaked cold through my soft shoes. Shards of stone cut into my feet as I lurched toward my baby girl.

“Watch your footing,” she said, though she knew it was enough work already to make progress up the hill. She knew. She wrapped her arms around me when I reached her. I thought for a hopeful moment that she might carry me on her back. Her big bag fell against me, a comforting sudden weight. We held each other.

“There you are,” she whispered, squeezing. My breath caught and seized.

We walked what felt like a twisting mile through the dale. Every step reminded me of my chair and I longed for it. I thought of dinner and sleep, I thought of gin. My ankles ached but it was my bones that truly troubled me. They locked and ground. I remembered a doctor cautioning me against activity, displaying a model of a normal leg and then removing some key elements, pushing the remaining bones together to demonstrate my future. There among the soaked and rotting wood I felt the doctor’s hands on my own legs and feet, twisting them as he watched my expression. I tried to conjure an image of my dear husband to busy my mind but could see only his bones as we cleared the ridge.

She had spoken of a tower. I thought it would crest the hill, a fortress against the sun, abounding stone, room enough for horses. Instead, I was faced with a broken place. The walls were charred to a cold crisp, its slate roof sagging, windows burst and gone, the door a seared gape. It sat alone in an airless glade, four simple walls ringed with a fading constellation of ash. Her great love was a ruin like any other.

The homesteader who built the place must have wanted dearly to be alone. He built far from any path, choosing an area flanked by boulders and fallen trees as if he hoped to dissuade even the limber animals who might otherwise discover the clearing. The trees bending deferent seemed to be shielding the unhappy space from errant light and the setting sun managed only to cast a dark purple wash across the ruined place, giving it the look of a drowned man.

“It burned,” she said. “Before I knew it.”

She walked ahead, arms swinging with purpose. I could not quite hear what she was saying and realized she was speaking to the house. She touched its threshold frame. I had a vision of the place aflame, its slate a foreign sky. She rubbed her soot-black fingers together before dropping to her knees like she was looking under a bed. She pressed her face against the wall. I heard her groan. My tank bounced on the terrain as I worked toward her and then passed her in the threshold.

Inside, it was warm and dark against the wind. Ash made a drifting slope in each corner. There was a trapped energy in the walls as if the ghost of the fire remained to charge it. If my chair was placed here, it would serve to complete a dark circuit.

And there, knees muddling the char, my girl kissed the brick. I watched despite my disgust, for what mother can truly stand to see her child in love. Hunched there on the ground, she licked and gagged, whimpering as sweetly as when she nursed from my breast.

Dragging my tank through blooming ash, I moved to her side. I leaned down and felt my spine jag in on itself, air bubbling from its subtle pores. I fell to one knee and then the other. The tube sprang from my nose and went spiraling into darkness. I crawled to my child where she lay, tonguing the wall. I gripped her, sensing her father with us there. I felt his disappointment in me.

“It’s perfect,” I said, wrapping my arms around her, mouth to her ear as her face pressed the wall. We collapsed and curled around each other on the ground, our breath a union, in no place like home.

Thanks are owed to Emily Bell at FSG and the whole team: Elizabeth Gordon, Karla Eoff, Justine Gardner, Ellen Feldman, Abby Kagan, Adrienne Davis, and Debra Helfand. Thanks also to the editors who published parts of this work prior to collection and whose thoughts helped shape this whole, particularly those who gave substantive notes: Emma Komlos-Hrobsky at

Tin House

, Ben Marcus at

The American Reader

, Cal Morgan at

52 Stories

, Jordan Bass at

McSweeney’s

, Michael Barron at New Directions, Tim Small at

VICE

, Drew Burk at

Spork

, Jesse Pearson at

Apology

, Matt Williamson at

Unstuck

, and Amber Sparks for Melville House. Thanks to Claudia Ballard for her devotion, Lauren Goldstein for her thoughts, Lee Shipman for his love and support, and to my family, near and far.

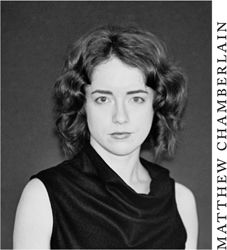

Amelia Gray

grew up in Tucson, Arizona. She is the author of three books:

AM/PM

,

Museum of the Weird

(winner of the Ronald Sukenick/American Book Review Innovative Fiction Prize), and

THREATS

(a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction). She lives in Los Angeles, where she is at work on a novel. You can sign up for email updates

here

.