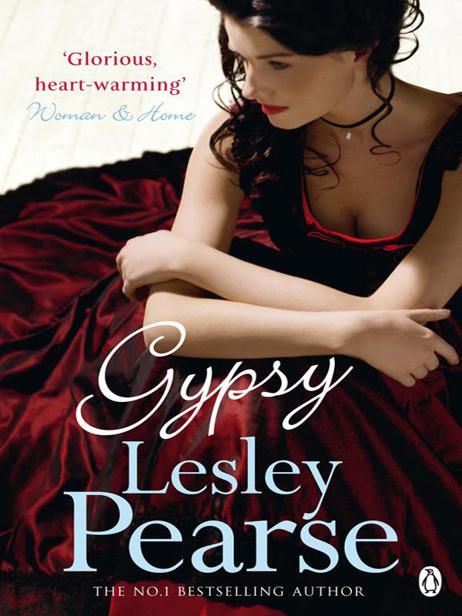

Gypsy

| Gypsy | |

| Lesley Pearse | |

| Penguin Books Ltd (2011) | |

| Tags: | Historical Saga |

Synopsis

Liverpool, 1893, and tragedy sends Beth Bolton on a journey far from home ...Fifteen-year-old Beth's dreams are shattered when she, her brother Sam and baby sister Molly are orphaned. Sam believes that only in America can they make their fortunes so, reluctantly leaving Molly with adoptive parents, brother and sister embark on the greatest adventure of their lives.Onboard the steamer to New York there are rogues aplenty. But Beth's talent with the fiddle earns her the nickname Gypsy - and the friendship of charismatic gambler Theo and sharp-witted Londoner, Jack. And after dodging trouble across America, finally the foursome head for the dangerous mountains of Canada and the Klondike river in search of gold.How far must Beth go to find happiness? And will her travels lead this gypsy to a place she can call home?

LESLEY PEARSE

Gypsy

MICHAEL JOSEPH

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Faith

Hope

A Lesser Evil

Secrets

Remember Me

Till We Meet Again

Father Unknown

Trust Me

Never Look Back

Charlie

Rosie

Camellia

Ellie

Charity

Tara

Georgia

To my grandson Brandon.

My greatest treasure and delight.

Chapter One

1893, Liverpool

‘Stop playing that Devil’s music and come and help me,’ Alice Bolton yelled angrily from the kitchen.

Fifteen-year-old Beth smirked at her mother’s description of her fiddle playing and was tempted to continue louder and wilder. But Alice had been very irritable recently and was likely to come in and snatch the fiddle, so Beth put it back into its battered case and left the parlour to do as she was asked.

She had only just reached the kitchen when a thud, quickly followed by the sound of heavy objects falling, came from the shop below their flat.

‘What on earth was that?’ Alice exclaimed, turning round from the stove with the teapot in her hand.

‘I expect Papa knocked something over,’ Beth replied.

‘Well, don’t just stand there, go and see,’ her mother snapped.

Beth paused on the landing, looking down over the banisters on to the staircase which led to the shop. She could hear something rolling around down there, but there was no sound of the cursing that usually accompanied any accidents.

‘Are you all right, Papa?’ she called out.

It was dusk, and although they hadn’t yet lit the gas lights upstairs, Beth was surprised to see no glow at the bottom of the stairs from the lights in the shop. Her father was a shoemaker, and as he needed good light for close work he always lit the lamps well before daylight began to fade.

‘What’s the clumsy oaf done now?’ her mother bellowed. ‘Tell him to leave his work for tonight. Supper’s nearly ready anyway.’

Church Street, one of Liverpool’s main shopping streets, had few carts or carriages upon it at seven in the evening, so her father should have heard his wife’s insulting remark clearly. When he didn’t respond to it, Beth thought he must be out in the privy in the backyard, and maybe a stray cat had got into the shop and knocked something over. The last time this had happened the contents of a glue pot ran all over the floor and it had taken hours to clean up the mess, so she ran down quickly to check.

Her father wasn’t in the privy as the door out to the yard was bolted on the inside, and when she went into the shop she found it in semi-darkness as the blinds had been pulled down.

‘Where are you, Papa?’ she called out. ‘What was all the noise about?’

There was no sign of a cat, or indeed anything out of place. The street door was locked and bolted; furthermore, he’d swept the floor, tidied his work bench and hung his leather apron up on the peg just as he did every evening.

Puzzled, Beth turned and looked towards the storeroom where her father kept his supplies of leather, patterns and other equipment. He had to be in there, but she couldn’t imagine how he could see anything with the door shut for even in bright daylight it was gloomy.

A strange sense of foreboding made her skin prickle and she wished her brother Sam was home. But he had gone out to deliver some boots for a customer a few miles away, so he wouldn’t be back for some time. She didn’t dare call her mother for fear of getting a clout for being ‘fanciful’, the expression Alice always used when she considered Beth was overreacting. But then her mother felt that a fifteen-year-old should have nothing more on her mind than improving her sewing, cooking and other domestic skills.

‘Papa!’ Beth called out as she turned the storeroom door knob. ‘Are you in there?’ The door only opened a crack, as if something was behind it, so she put her shoulder to it and pushed. She could hear a scrape on the flagstone floor, maybe a chair or box in the way, so she pushed harder until it opened enough to see round it. It was far too dark to make anything out, but she knew her father was inside, for she could smell his familiar odour, a mixture of glue, leather and pipe tobacco.

‘Papa! Whatever are you doing? It’s pitch dark,’ she exclaimed, but even as she spoke it struck her that he might have been knocked out by something falling on him. In panic she rushed back across the shop to light the gas. Even before the flame rose enough to illuminate the glass mantle and bathe the shop in golden light, she was back at the storeroom.

For a second or two she thought she was seeing a large sack of leather in front of the storeroom window, but as the shop light grew brighter, she saw it was no sack, but her father.

He was suspended from one of the hooks on the ceiling, with a rope around his neck.

She screamed involuntarily and backed away in horror. His head was lolling to one side, eyes bulging, and his mouth was wide open in a silent scream. He looked like a hideous giant puppet.

It was all too clear now what the sound they’d heard earlier had been. As he’d kicked away the chair he’d been standing on, it had knocked a box of oddments, tins of shoe polish and bottles of leather dye, on to the floor.

It was early May, and just a few hours ago Beth had been grumbling to herself as she walked to the library because her father wouldn’t allow her to get a job. She had finished with school the previous year, but he insisted daughters of ‘gentlefolk’ stayed at home helping their mothers until they married.

Sam, her brother and senior by one year, was also disgruntled because he was apprenticed to their father. What Sam wanted was to be a sailor, a stevedore, a welder, or to do almost any job where he could be outside in the fresh air and have the company of other lads.

But Papa would point out the sign above the door saying ‘Bolton and Son, Boot and Shoemaker’, and he expected Sam to be just as proud now to be that ‘Son’ as he himself had been when his father had the sign made.

Yet however frustrating it was to have their lives planned out for them, both Beth and Sam understood their father’s reasons. His parents had fled from Ireland to Liverpool in 1847 to escape slow starvation during the potato famine. For years they lived in a dank cellar in Maiden’s Green, one of the many notorious, squalid slum ‘courts’ that abounded in the city. Frank, Sam and Beth’s father, had been born there a year later, and his earliest recollections were of his father going from door to door in the better parts of Liverpool with his little cart to find shoes and boots to mend, and his mother going out each day to work as a washerwoman.

By the time Frank was seven he was helping both his parents by collecting and delivering boots for his father or turning the handle of the mangle for his mother. It was impressed on him, even when he was hungry, cold and tired, that the only way out of poverty was to work hard until they had saved enough money to get a little cobbler’s shop of their own.

Alice, Sam and Beth’s mother, had an equally tough childhood, for she had been abandoned as a baby and brought up in the Foundling Home. At twelve she was sent out to be a scullery maid, and the stories she told of the exhausting work and the cruelty of the cook and housekeeper were the stuff of nightmares to Beth.

Frank was twenty-three when he met sixteen-year-old Alice, by which time he and his parents had achieved their goal and had a tiny shop with two small rooms above. Alice had often said with a smile that her wedding day was the happiest day of her life because Frank took her to live with his parents. She still had to work just as hard, but she didn’t mind that, for the purpose was to get even better premises where her father-in-law and husband could make shoes instead of just repairing old ones.

The hard work finally paid off and brought them here to Church Street, with two floors above the shop, where both Sam and Beth were born. Beth couldn’t remember her grandmother, as she’d been only a baby when she died, but she had adored her grandfather and it was he who taught her to play the fiddle.