Hacking Happiness (26 page)

Authors: John Havens

Long-term happiness is cultivated. It doesn’t simply arrive. Like the Founding Fathers noted, it’s the pursuit of happiness that will bring us greatest meaning when we strive to accomplish a goal tailored to who we are. In my case, music is where I achieve a state of flow, or what Csikszentmihalyi also refers to as “optimal experience.” Flow isn’t always pleasant—athletes may be in a physical state of agony while achieving optimal experience. But it’s this type of almost insurmountable challenge that brings deep satisfaction: “The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

4

In a 1997 article for

Psychology Today

, “Finding Flow,” Csikszentmihalyi reviewed a number of central premises of his book while also giving examples for how to find flow in different parts of our lives. He also describes a technique he created for sampling survey participants called the experience sampling method, or

ESM, that laid the groundwork for many apps within the quantified self movement. Developed at the University of Chicago in the early 1970s, ESM provides a “virtual filmstrip of a person’s daily activities and experiences.”

5

For ESM, Csikszentmihalyi and his team utilized electronic pagers that would collect information from survey participants throughout the day, including who they were with, what they were doing, and their state of consciousness. The team collected over seventy thousand pages from more than two thousand participants.

A modern example of this pager method can be found in the Memoto camera, a small wearable camera that takes pictures multiple times throughout the day. A form of quantified self in terms of tracking behavior, the camera was also created for lifelogging. Lifelogging refers to the idea of recording your life and reviewing the images to better savor your existence.

I had the good fortune to be a part of a documentary film,

Lifeloggers

, that Memoto created, which features a number of great minds in the quantified self and wearable computing movements. It’s also worth a watch to see how Csikszentmihalyi’s ideas of experience sampling have evolved. To get a sense of how Memoto works, you can watch their Moment View Video, where pictures taken every thirty seconds are assembled into a slide show format.

6

Lifelogging is not just a trend for the techie crowd. Recent studies have shown that reviewing photographs from your day can help in memory retention or even curbing dementia. Thought leader Brenda Milner from McGill University describes some of these types of findings in the video “Inside the Psychologist’s Studio”

7

from the Association for Psychological Science.

Lifelogging can also provide a forum for activism, where a person’s recorded photos or videos can be used for the common good. Steve Mann, whom many credit as being the father of wearable computing, coined the term “sousveillance” in a paper he wrote with colleagues Jason Nolan and Barry Wellman in 2003,

“Sousveillance: Inventing and Using Wearable Computing Devices for Data Collection in Surveillance Environments.”

8

In the paper, Mann and his colleagues challenge a society that has become overly surveillance-focused to allow individuals to wear devices so they can record their own actions. Dubbing this activity “sousveillance,” from the French words

sous

(below) and

veiller

(to watch), this practice lets people “track the trackers” in their lives. I interviewed Oskar Kalmaru, cofounder of Memoto, about lifelogging being used for this type of antisurveillance and other types of activism as well.

Tracking yourself and the close environment around you has indeed proven to protect people from surveillance regimes. During the Arab Spring, an Egyptian blogger was accused of being involved in riots in Cairo, but thanks to having tracked his location, he could show that he hadn’t even been in Egypt at the time. As self-tracking becomes even easier and more intertwined with the devices and services we already use, I think we will see an exploding number of use cases like these.

9

In a blog post on the Memoto site,

Lifelogger

filmmaker Amanda Alm relates another, newer use of lifelogging that has become popular. Russian dashboard cameras have recorded footage of people being kind as well as unique documentation of a meteorite that crashed in 2013. In Alm’s words, “Drivers having dash cams attached to their cars is common [in Russia], and what’s captured can provide valuable evidence for situations like accidents, etc. Those dash cams were invaluable in gathering lots of material on that meteorite, something useful for scientific analysis.”

10

Lifelogging as empowered by the digital tools of quantified self is revolutionizing how we study flow. Like the Lively platform we discussed in Chapter Four, sensors are also helping us understand how our daily activities affect our health. A February 2013 report

from the California HealthCare Foundation,

Making Sense of Sensors: How New Technologies Can Change Patient Care

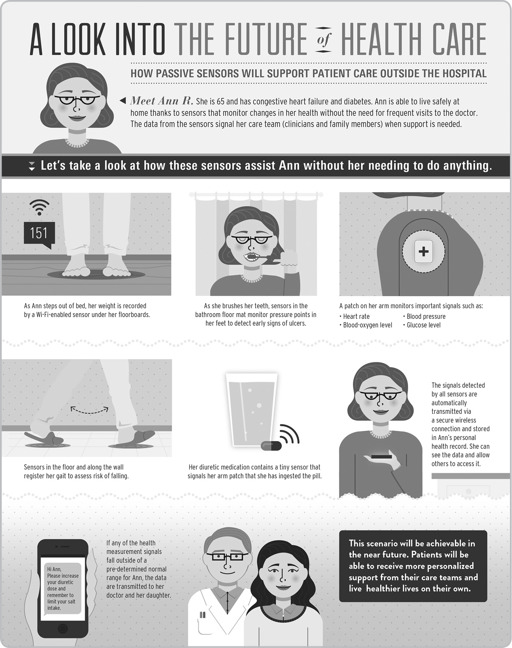

by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, opens with this fictional vignette describing how sensor technology could help monitor seniors for assisted living purposes:

When Ann R., a sixty-five-year-old woman with congestive heart failure and diabetes, steps out of bed in the morning, her weight is recorded by a Wi-Fi–enabled sensor located

under the floorboards. This is just one of several sensors that keep a close watch on Ann’s health without her having to do anything at all. The data detected by all the sensors are automatically transmitted via a secure wireless connection and stored in her personal health record in a cloud-based computer server. If any of the health measurement signals falls outside of a predetermined normal range for her, the data are transmitted to her clinician as well as to a family member designated by Ann.

11

These types of sensors add a critical component to the study of flow that Csikszentmihalyi didn’t have available for his initial work regarding the experience sampling method: passive data collection. While using a beeper throughout the day produced remarkable insights about people’s behavior and well-being, their responses were still affected by survey bias. Meaning, on some level, they knew their answers were being recorded. They may also have been annoyed by the interruption of the beeper that could have affected their survey responses.

This doesn’t minimize the early work done via the experience sampling method. On the contrary, the precedent established by Csikszentmihalyi’s work means we can get the best of two complementary sets of data collected by active and passive means. As a reminder:

- Active data collection—people are aware their thoughts or actions are being recorded.

- Passive data collection—people give permission to be recorded, but then forget about the sensors or other tools tracking their behavior.

In Chapter One, I related three aspects of a person’s well-being and identity in the Connected World:

- Subjective well-being—how you perceive your happiness and actions

- Avataristic well-being—how you project your happiness and actions

- Quantified well-being—how devices record your actions reflecting your happiness

It’s our quantified well-being that is now adding a massive new dimension of insights to the data collected about our lives. The information generated about your actions can start to reveal what brings you meaning in ways we’ve never had access to before.

Flow in Action

In his

Psychology Today

article “Finding Flow,” here’s how Csikszentmihalyi talked about achieving a state of flow during leisure time:

In comparison to work, people often lack a clear purpose when spending time at home with the family or alone. The popular assumption is that no skills are involved in enjoying free time, and that anybody can do it. Yet the evidence suggests the opposite: Free time is more difficult to enjoy than work. Apparently, our nervous system has evolved to attend to external signals, but has not had time to adapt to long periods without obstacles and dangers. Unless one learns how to use this time effectively, having leisure at one’s disposal does not improve the quality of life.

12

This is compelling information and runs contrary to the idea that we can get happier just by consuming as much entertaining media as possible. The article relates statistics saying that U.S. teenagers experience flow 13 percent of the time when they watch TV versus

34 percent doing hobbies and 44 percent playing sports or games. “Yet these same teenagers spend at least four times more of their free hours watching TV than doing hobbies or sports. Similar ratios are true for adults.”

13

The trick with flow is that a person needs to experience it regarding a new activity to understand how powerfully it can improve their lives. Discovering flow in your life requires investment that you’ll only uncover if you track what works and what doesn’t.

Sensor data is also starting to affect flow at work. Ben Waber, cofounder and CEO of Sociometrics Solutions and author of

People Analytics: How Social Sensing Technology Will Transform Business and What It Tells Us about the Future of Work

, wrote an article for

MIT Technology Review

about augmented social reality, an evolving technology platform that utilizes sensors to shape the physical environment of an office based on interpersonal relations. While flow as defined by Csikszentmihalyi involves a person understanding their behavior that provides optimal experience, this trend of data-supported social interactions will factor into how we create meaning in future work situations. Here’s how Waber describes this new technology in “Augmenting Social Reality in the Workplace”:

Augmented social reality is about systems that change reality to meet the social needs of a group. For instance, what if office coffee machines moved around according to the social context? . . . By positioning [a] coffee robot in between two groups, for example, we could increase the likelihood that certain coworkers would bump into each other. Once we detected—using smart badges or some other sensor—that the right conversations were occurring between the right people, the robot could move on to another location. Vending machines, bowls of snacks—all could

migrate their way around the office on the basis of social data.

14

I love visualizing how this might look in the future. Would these robots penalize me if I grabbed too many snacks? If I don’t steam my espresso right, will the coffee machine ignore me for two weeks? In terms of helping to facilitate social interactions, I do see this technology providing worthwhile insights for companies willing to experiment. I’d also want employees to be able to access data from machine interaction to gain insights about their own behavior, however. In this way, employees could examine personal data that could give them hints about where they could find more flow at work.

Flow has been shown to increase with political activism. In an article for the

Pacific Standard

, “Get Politically Engaged, Get Happy?”

15

Lee Drutman reports on the work of two psychologists, Malte Klar and Tim Kasser, who found a link between political activism and a person’s sense of well-being.

16

The pair were interested in studying eudaimonic happiness versus hedonic happiness with regard to civic engagement. Where life has a sense of purpose or direction, eudaimonia and flow can increase. Connecting with a group is also a form of happiness focusing on social well-being that Klar and Kasser were interested in studying regarding activism.

After conducting surveys with sample groups, asking about their histories and attitudes toward activism, the researchers discovered that being an activist correlated with being happy. Political activism gave people a greater sense of purpose and connection to community than those who weren’t participating. We crave connection to our communities and to work for a purpose that is greater than ourselves.

Flow can also be experienced in educational settings. The Key Learning Community in Indianapolis has incorporated flow into their teaching methods to help encourage children to identify the

areas where they find connection in their studies.

17

In an article from

Edutopia

, Csikszentmihalyi describes some of the ways the Indianapolis school has incorporated flow, including the use of a “Flow Room,” where students can spend an hour a week exploring any subject that interests them. The school also hired a video technician who, along with teachers, interviewed each child at the beginning of the school year, asking them what they hoped to achieve by the end of the year. Throughout every semester, in a video-journal format, kids would update their tapes with recent accomplishments. Csikszentmihalyi describes the results: