Hacking Politics: How Geeks, Progressives, the Tea Party, Gamers, Anarchists, and Suits Teamed Up to Defeat SOPA and Save the Internet (17 page)

Authors: and David Moon Patrick Ruffini David Segal

Tags: #Bisac Code 1: POL035000

The Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) was most commonly criticized because its passage would have allowed the U.S. Government to curtail online publishing without due process, violating the cherished right of freedom of speech. Opponents argued that the bill grossly overreached and took a sledgehammer to protect intellectual property rights where a scalpel at most may be needed. But too few people were aware that SOPA could also deprive Americans of access to safe and affordable prescription medication. Access to affordable prescription medication is often a matter of life and death. Blocking it transcends traditional censorship issues and becomes a basic human rights violation.

This is the story of how the pharmaceutical and U.S. pharmacy industries supported SOPA to assert greater control over the online distribution of prescription medication and protect their high prices. They joined the movie and music industries to support SOPA in search of special government protections for their profits

For full disclosure, I’m vice president of

PharmacyChecker.com

, which helps consumers find safe online pharmacies and compare their drug prices. SOPA’s passage could have led to private or government actions to shut down

PharmacyChecker.com

, even though we do not sell prescription medication but only provide information.

PharmacyChecker.com

joined a coalition of non-profit organizations, businesses, and individual Americans called

RxRights.org

, which advocates for safe personal prescription drug importation. When SOPA’s predecessor, the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act (COICA), was introduced, it was clear as day that the pharmaceutical industry had its paws on this legislation. Defeating SOPA became

RxRights.org

’s greatest priority.

SOPA’s Section 105, called “Immunity For Taking Voluntary Action Against Sites That Endanger The Public Health,” made it a vehicle to prevent Americans’ access to safe international online pharmacies, meaning, for our purposes, non-U.S., international mail-order pharmacies, where brand name drug

prices are often 85% lower than at U.S. pharmacies. The provision, in effect, defined safe international online pharmacies as dangers to the public health, making them subject to takedown actions, such as refusal of service by registrars. This section was more pernicious than those dedicated to copyrighted materials. As important as is the free speech right to creative content, the right to affordable and necessary medication is often a matter of life or death. Not so for the shared MP3 download.

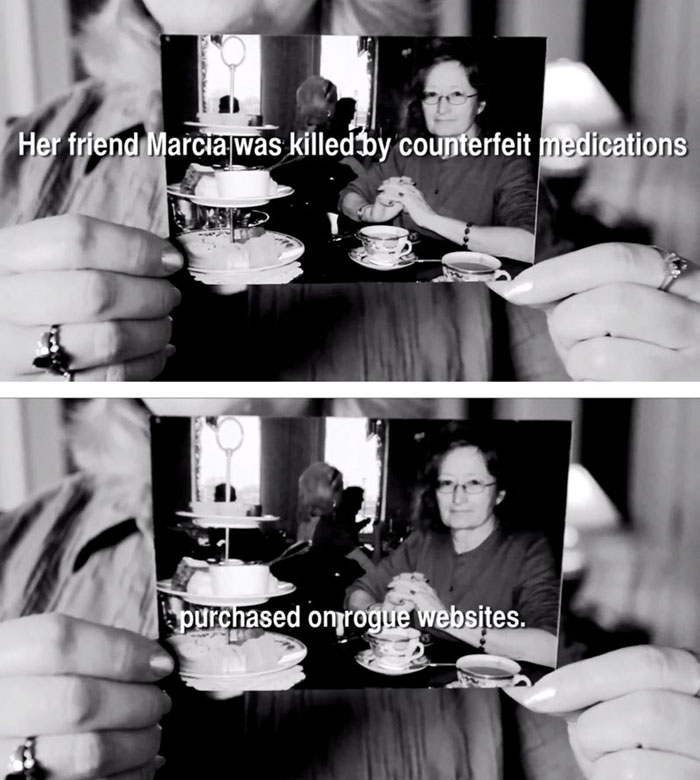

The industries backing SOPA/PIPA used as a scare tactic the fear of fake prescription drugs to justify online censorship. In reality, the legislation made no distinction between legitimate websites selling safe pharmaceuticals and those (of which there are many) selling potentially bad medication. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a SOPA-supporter, even produced a web video highlighting the death of a person who had taken fake drugs purchased online, attempting to conflate deadly counterfeit drugs with copyright infringement.

Drug affordability is a serious problem in America. Almost half of Americans—and 90% of seniors—rely on prescription medication to treat or prevent disease. The Commonwealth Fund reported that in 2010 forty-eight million Americans between the ages of 19–64 (not including seniors) did not fill a prescription because of cost. According to the National Consumers League, one hundred twenty-five thousand Americans die annually because they do not take needed medication. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reports $290 billion in additional healthcare spending (for more emergency room visits and hospitalizations) resulting from failure to take needed medicines.

Price controls in other countries mean that drug prices are much lower abroad. Before the Internet, Americans required travel to Canada or Mexico for lower-priced medicine. In fact, in the beginning of the last decade several members of Congress led constituents on bus trips to Canada for the purpose. Now the Internet has created a marketplace in which Americans access lower-priced and safe international online pharmacies.

U.S. laws serve the economic interests of pharmaceutical companies at the expense of American consumers. Federal law technically prohibits individuals from importing the same medicine sold in U.S. pharmacies from Canada and other countries, but the practice, while discouraged by the FDA, is generally permitted.

Let’s examine the FDA’s position on personal drug importation. The FDA has regulations in place to protect the U.S. drug supply, presumably to insure safety and efficacy. The FDA cannot guarantee the safety of medicines sold in other countries, so for their own protection Americans are not supposed to buy medication from Canada or anywhere.

But how strong is the FDA “guarantee” of the domestic supply to begin with? Are FDA-approved drugs sold here really safer than personally imported ones from licensed sources? If they’re not, then the law protects pharmaceutical profits from lower cost competition, but not the public health.

America has experienced two tragedies over the past five years due to drug quality lapses: neither had anything to do with international online pharmacies. The first occurred in 2007–2008 when tainted Heparin imported from China killed about one hundred fifty Americans. The second occurred last year when forty-six people were killed and six hundred sickened by fungal meningitis contracted by bad steroid injections, which were manufactured and sold by a Massachusetts compounding pharmacy.

Americans might believe that most of our pharmaceuticals are “American.” The truth is that most are foreign! According to the FDA, 80% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)—main ingredients—in prescription medication

sold in U.S. pharmacies are imported from countries all around the world, mostly India and China. This is not a new development. According to a Government Accounting Office report from 1998, 80% of APIs in “American” medications were imported. Drug and drug component importation is the pipeline of medicine into U.S. pharmacies, but the industry seems to use every available ploy and falsehood to control the pipeline and thus its prices—such as SOPA.

Americans are lead to believe that the FDA vigilantly maintains a “closed” drug supply chain. Yet a GAO report from 2010 based on FDA’s data found that “of the three thousand seven hundred sixty-five foreign establishments in FDA inventory for fiscal year 2009, there were two thousand three hundred ninty-four foreign establishments that may never have been inspected by the FDA …” In other words, the FDA’s claim that it can’t guarantee the safety of personally imported medicines should extend to

legally imported

APIs and finished products.

Gaps in foreign drug plant inspections are serious but there are also many documented failures at American plants. According to Erin Fox, manager of the Drug Information Service at the University of Utah, “In the industry, everyone knows that all of the factories are in terrible shape … I think people think this is a foreign outsourcing problem, but these factories are in our own country.” A recent article in the

New York Times

reported on the unsanitary conditions of some U. S. manufacturing plants, including discovery of rusty tools, mold, and a barrel of urine at one plant; at another, human hair and fungal growth in pharmaceutical vials.

America’s domestic pharmaceutical distribution system is far more chaotic than in many other countries. The U.S. has thousands of wholesalers trading medication in a domestic gray market marred by loose and inconsistent state regulations. It is through these offline channels that counterfeit and adulterated medicines have often found their way to and harmed patients.

The drug and pharmacy industries misinform policy-makers and the media that personal drug importation from all online pharmacies is dangerous. When Canadian pharmacies first went online about thirteen years ago, the pharmaceutical industry audaciously propagated that “drugs from Canada” were not safe. They now argue that online pharmacies pretend to be “Canadian”—conceding that Canadian pharmacies are safe—but actually sell medications imported from other dangerous countries. The truth is that online pharmacies can be dangerous if people order from dangerous foreign or domestic sources. But international online pharmacies can be as safe as U.S. pharmacies, and for many Americans it is their only channel of affordable medication.

Studies show the high degree of safety found at properly credentialed international online pharmacies. They require valid prescriptions, and meds are dispensed by licensed pharmacists working in licensed pharmacies, and are mailed safely to the patient, all of which are verifiable by the consumer through companies like

PharmacyChecker.com

. One 2012 study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, called “In Whom We Trust: The Role of Certification Agencies In Online Drug Markets,” demonstrated the safety of and savings found at credentialed international online pharmacies. All of them

required a prescription and passed all drug authenticity tests and their prices were on average 52% lower.

The law against personal drug importation has been “on the books” for years, yet the FDA (to its credit) has never prosecuted anyone for importing prescription medication for his or her own use. It is reasonable to view the practice as, de facto, decriminalized. Over a million Americans annually import medication for personal use from online pharmacies, and many millions have over the past decade. The FDA’s enforcement policies are usually limited to disrupting illegal wholesale drug importation, and they have stepped up enforcement actions against demonstrably dangerous online pharmacies from reaching Americans but mostly left alone those known to operate safely.

Recently, FDA seems more willing to overreach in its enforcement efforts, notably getting Google, Bing, and Yahoo to stop permitting Canadian and other online pharmacies, whether safe or not, from online advertising. Congress recently passed a bill to facilitate greater seizures and destruction of personally imported medication by Customs and Border Patrol (CBP). The FDA is spending more tax-payer dollars on “public education” campaigns to allegedly help Americans find safe U.S. online pharmacies, but discouraging purchases of affordable medication from all international online pharmacies.

Why is the government doing this? Over the last decade, pharmaceutical interests have spent almost two billion dollars lobbying U.S. government branches to meet commercial goals, such as preventing drug price negotiations and new importation laws to lower domestic prices. Additionally, the Obama administration made a deal with the pharmaceutical industry; the administration would drop its tacit support of drug importation in exchange for industry support of Obamacare and modest price rebates to government health care programs.

Had SOPA become law, search engines, domain registrars and registries, credit card companies, payment processors and advertisers would be encouraged to refuse their services to safe online pharmacies. Supporters of SOPA obtusely pointed to the bill’s language on online pharmacies to argue that the bill was not only about protecting intellectual property and copyrights but protecting lives. Their conflation between dangerous and safe online pharmacies is found in SOPA’s Section 105 definition of “sites that endanger the public health”:

(2) INTERNET SITE THAT ENDANGERS THE PUBLIC HEALTH—The term “Internet site that endangers the public health” means an Internet site that is primarily designed or operated for the purpose of, has only limited purpose or use other than, or is marketed by its operator or another acting in concert with that operator for use in offering, selling, dispensing, or distributing any prescription medication, and does so regularly without a valid prescription; or offering, selling, dispensing, or distributing any prescription medication that is adulterated or misbranded.

The language looks reasonable but was intentionally deceptive because safe, effective, genuine, and unadulterated prescription drugs can be deemed

“misbranded” under the U.S. Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). If the label on the packaging is slightly different from FDA requirements, even if the pill is the exact same, then the medicine is sometimes categorized as “misbranded”. Thus, under SOPA, websites that sell genuine medication may nevertheless “endanger the public health.”

Interestingly, a statement published by the Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) in support of SOPA was not ambiguous in this regard:

PhRMA applauds the introduction of the Stop Online Piracy Act … America’s pharmaceutical research and biotechnology companies invest billions of dollars each year researching and developing new medicines, and they depend on strong and reliable IP protections to continue their important work in research labs across the nation. Intellectual property rights afforded to America’s pharmaceutical research companies help them recoup their incredible investments in the discovery of new medicines, and give them a chance to survive and fund further research in a highly competitive environment.

A passage in this compilation written by Ernesto Falcon of Public Knowledge, a leading organization that battled SOPA and its legislative predecessors, is very descriptive here. Mr. Falcon writes of his jousts on Capitol Hill: “Sometimes the discussion would degrade into arguments over whether the government should just stand idly by while grandma purchased bad drugs on the Internet and subsequently died—the lead sob story lobbyists used to make the case for passage.” Thus SOPA’s blatant effort to block Americans from protecting their own health by online access to safe medications was camouflaged as intended to protect the public health.