Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love (22 page)

Read Hands of My Father: A Hearing Boy, His Deaf Parents, and the Language of Love Online

Authors: Myron Uhlberg

The Spider-Man of Ninth Street

T

wenty years before the nerdy high school nonentity Peter Parker was bitten on his hand by a radioactive spider, transforming him instantly into Spider-Man, I decided I could climb up the brick face of my apartment house wall. I arrived at this startling conclusion after only a little practice and even less thought.

I’m practicing to be Spider-Man.

Like every other kid in Brooklyn in 1943, I was a great fan of the King of the Jungle, Tarzan. I saw every one of his movies at our local movie house, the Avalon Theater, the week it was released. And I bought every one of his comic books the minute it hit the rack at our local candy store. Indeed, although I wasn’t much of a student in my school-based subjects, I was a summa cum laude in anything depicted in movies and comic books. Tarzan’s extraordinary ability to climb trees like an ape, and to swing from trees on the vines that grew in their upper reaches, inspired me to attempt my own vine-swinging feats. Thus I swiped a length of clothesline and fashioned a Brooklyn version of an African vine.

One day, with my “vine” wound tightly around my waist, I climbed a tree that stood in our backyard. All day long I scampered up and down the length of that tree, my clothesline vine attached to one of its topmost branches so that I could swing in soaring arcs that took me over our neighbor’s garage roof. Eventually, having exhausted the possibilities of simulating an African jungle experience in one tree, I lay along a limb and dreamed of further adventures.

Emboldened by my success at climbing a tree trunk and swinging from the end of a clothesline, I decided that, like Tarzan, I would use this means of transportation to move about my “jungle”—West Ninth Street, Brooklyn, New York.

But my “jungle” was rather sparse, its trees few and far between. Swinging from one to another required skills that would have taxed even Cheetah, not to mention Tarzan. Still, I was determined to expand my fantasy to its outermost limits, and so I soon settled on an interesting alternative: the telephone cables that snaked their way, high overhead, from pole to pole, down the backyards of my street. Looking up at them with my hyperactive ten-year-old imagination, I could easily visualize them as the thick jungle canopy I would soon be negotiating with my clothesline.

One afternoon, my “vine” wound tightly around my waist, where it performed no function except in my mind, I climbed a telephone pole in my backyard. Grasping the cable at the top, I began my progress above the backyards of my block, making my way slowly, hand over hand, from one pole to the next, until I reached Avenue P, the end of my street. Not bad, I thought, then reversed my position on the cable and made my way in the opposite direction until I reached Quentin Road. Had Tarzan as a boy lived in Brooklyn, could he have done any better?

If any neighbors had happened to glance out their rear windows, they would have seen a kid with a clothesline wound in coils around his waist, dangling from the telephone wires, with a determined expression of absolute concentration on his face. Yes, I

was

the king of my jungle. Fortunately, no one saw me—or reported me to my parents, as they would certainly have done if they had—and I was able to perform this feat several days in a row until, tiring of the rather restricted movements available to me on the single telephone line running up and down the “rooftop” of my jungle, I returned to my ample collection of Tarzan comic books to investigate possibilities for further adventures.

Using the amazing powers of deduction with which all Brooklyn kids were genetically endowed to enable them to transform their environment into something more exotic, I hit on the idea that the brick face of my apartment house was the sheer face of a jungle escarpment. Of course, I didn’t know what an escarpment was, but when I looked upward at the wall, indelibly etched in my mind was the image of Tarzan climbing a sheer cliff face, followed closely by a lion. Holding that image in my mind, I imagined a lion on West Ninth Street stealthily stalking me.

And so it was that one day I found myself clinging to the face of my apartment house wall, like a spider on steroids, fingers and sneaker-toes embedded between the bricks, two stories above the ground. It was slow going, but brick by brick I proceeded upward, the hot breath of the lion warming my feet, its deep cough throbbing in my ear.

Ignoring the real-life screams of the neighborhood mothers rising from the street below me, I crawled up and up, mindful of the fire escape railings just inches to my right. My fail-safe plan was to grab the rail of a handy fire escape if I should begin to fall.

Just at the moment I was sure I had escaped the lion, Mrs. Abromovitz emerged from her bedroom window, rags in hand, to perform her once-a-week window-cleaning ritual. Settling her ample rump comfortably on the windowsill, she lowered the overhead window onto her lap for security, turned, and saw me clinging to the wall, inches from her face. Her single scream put to shame the collective yells from the gaggle of neighborhood

yentas

below. Theirs were but a murmuring breeze, split by the thunder of her voice.

The lowered window kept her nailed to the windowsill, as she sat stunned in fright.

I froze, stuck to the face of the building, paralyzed by the sound. Regaining my wits, I knew I had to get out of there quickly. But up or down? Down below waited my imaginary foul-breathed lion and the outraged

yentas

—infinitely more fearsome predators—so up I went, up to our apartment’s third-floor fire escape.

As my mother was deaf, she did not hear me climb through her bedroom window. And since I had my own key to our apartment, she did not know that I had entered it from the fire escape. Not for the first time I realized that for a kid like me, having deaf parents had some practical advantages.

But I knew there would be a reckoning.

That evening, when my father came home from work, three of our neighbors were stationed at our front door. They had all written down their fervid accounts of my escapade, and now they jabbed the resulting narratives in my father’s weary face.

Mrs. Abromovitz had yet to emerge from her apartment. Her meek husband was faithfully attending to her as she lay in her bed, to which she had immediately retired upon regaining her senses.

My father and I had a most interesting conversation that evening, a conversation that taxed to the utmost my signing comprehension. But, as ever, my father’s expressive use of his beloved language left no doubt in my mind what lay in store for me should I

ever again

attempt a similar stunt.

The lion was not seen or heard from again on our block. The fearsome sounds of those

yentas

no doubt drove him back to Africa.

15

A Boy in Uniform

E

very night after dinner, while my mother was doing the evening dishes, my father sat at the kitchen table with my brother and me and read to us—in sign—from the first page of the

New York Daily News,

which his labors in the composing room had helped to create. In its early years World War II was going badly. We were losing on every front, one battle after another. “Don’t worry,” his hands told Irwin and me with perfect conviction, “America has never lost a war.”

I could read most of the words on the front page for myself. Even the ones I didn’t know, I could sound out. But I much preferred that my father read the front page to me. Words like

war,

and

battles,

and

army,

and

shell,

and

bomb

were just words to me, as were

wounded

and

dead.

But when my father’s expressive hands turned these words into sign, they came alive. In the movement of his hands, I could see the fall of bombs, the flight of shells, and the movements of vast armies; I could hear the cries of the wounded and the stillness of death. His hands told me of the Bataan Death March, and I could see our weary soldiers dragging their broken bodies along the endless dusty roads, and I could feel the jabs of bayonet points as their cruel Japanese guards prodded them. I could see the shells erupting on the decks of battleships at the Battle of Midway, the fires and explosions bursting into the air, the sailors abandoning ship as jagged holes appeared at the waterline, and the oil-stained sea becoming clotted with sailors clinging to floating debris. My brother would sit at his side of the table, too young to comprehend what all the excitement was about, but fascinated by the dramatic signs and thrilled by every minute of the performance.

I had a vivid imagination as a young boy and could readily turn words into images in my mind. But the constant commerce between words and signs that was so much a part of my life greatly expanded this ability.

The evening readings with my father were the high point of my day, and I became a great student of the war. My friends would have to wait for the Pathé newsreel that was shown every Saturday afternoon on the silver screen at our local movie house for a visual chronicle of the progress of the war. I, on the other hand, could watch it every night of the week on the human screen of my father’s hands.

In 1944 the tide of war was turning in our favor. We were on the march. I thrilled to my father’s signs every night, as he read to me the headlines that trumpeted the advances our soldiers were making up the boot of Italy.

In June Rome was liberated.

That same month the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy. D-Day had finally arrived. Slowly but surely our troops were slogging their way to Paris.

The newspaper was filled with pictures of soldiers in uniform; soldiers in foxholes; soldiers in chow lines; soldiers at the front; and even dead soldiers. All wore uniforms of one kind or another, theirs and ours.

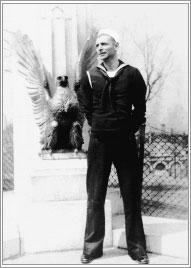

I wanted a uniform of my own.

My mother’s youngest brother, Milton, was a captain in the army, a paratrooper posted somewhere in Europe, and then in Burma. He sent me a bayonet holder and a bandolier. I wore them around the apartment.