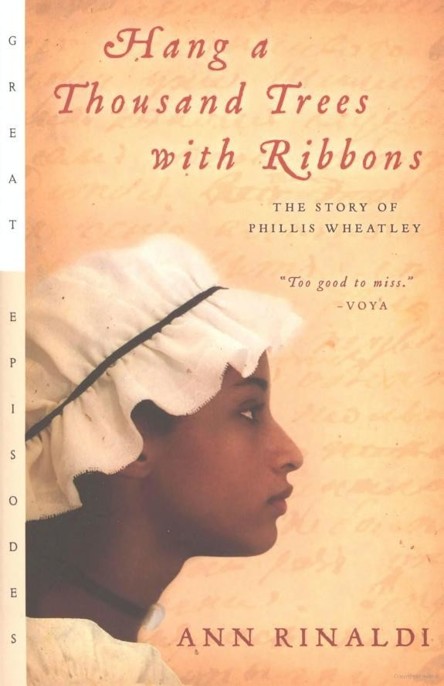

Hang a Thousand Trees with Ribbons

Read Hang a Thousand Trees with Ribbons Online

Authors: Ann Rinaldi

The Story of Phillis Wheatley

Ann Rinaldi

GULLIVER BOOKS

HARCOURT, INC.

Orlando Austin New York

San Diego Toronto London

Copyright © 1996 by Ann Rinaldi

Reader's guide copyright © 2005 by Harcourt, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of

the work should be mailed to the following address:

Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

First Gulliver Books paperback edition 1996

Gulliver Books

is a trademark of Harcourt, Inc., registered in

the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rinaldi, Ann.

Hang a thousand trees with ribbons:

the story of Phillis Wheatley/Ann Rinaldi.

p. cm.

"Gulliver Books."

Includes bibliographical references.

Summary: A fictionalized biography of the eighteenth-century African

woman who, as a child, was brought to New England to be a slave,

and after publishing her first poem when a teenager, gained renown

throughout the colonies as an important black American poet.

1. Wheatley, Phillis, 1753–1784—Juvenile fiction. [1. Wheatley, Phillis,

1753–1784—Fiction. 2. African Americans—Fiction. 3. Women poets—

Fiction. 4. Salves—Fiction. 5. Poets—Fiction. 6. Massachusetts—

History—Colonial period, ca. 1600–1775—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.R459Han 2005

[Fic]—dc22 2004054033

ISBN

0-15-205393-X

Text set in Fournier

Designed by Kaelin Chappell

G H

Printed in the United States of America

In memory of my aunt Jo

TO BE SOLD

A Parcel of likely Negroes, imported from Africa, cheap for cash or short credit; Enquire of John Avery, at his House next Door to the White-Horse, or at a Store adjoining to said Avery's Distill-House, at the South End, near South Market; Also, if any Persons have any Negro Men, strong and hearty, tho' not of the best moral character, which are proper Subjects for Transportation, may have an Exchange for small Negroes.

—

From an advertisement in both the

Boston Evening Post

and the

Boston Gazette and Country Journal

for July 29, 1761, and several weeks thereafter

Sir You having the Command of my Schooner Phillis your orders Are to Imbrace the First Favorable Opertunity of Wind & Weather & proceed Directly for the Coast of Affrica, Touching First at Sinagall if you fall in with it On your arrival then Cum to Anchor with your VeSsell & go up to the Facktory in your Boat & see if you Can part with Any of your Cargo to Advantage ... if you Could Sell the whole of your Cargo there to a Good Proffett & take Slaves & Cash Viz. Cum Directly Home.... You must Spend as little Time as poSsible at Sinagal & then proceed Down the Coast to Sere Leon & then make the best Trade you Can from place to place till you have disposed of all your Cargo & purchase your Compleat Cargo of Young Slaves which I Suppose will be about 70 or Eighty More or LeSs I would Reacommend to you gowing to the Isle Delos if you Cant Finish at Sereleon ... be sure to bring as Few Women & Girls as possibl ... hope you wont be Detained Upon the Coast Longer than ye 1st of May by Any Means, the Consequence you know We have Experienced to be Bad, You & your people & Slaves will get Sick which will ruin the Voyage. Whatever you have left Upon hand after April, Sell it altogeather for what you Can Get if even at the First Cost Rather than Tarry Any Longer ... be Constantly Upon your Gard Night & Day & Keep good Watch that you may Not be Cutt of by Your Own Slaves tho Neavour So Fiew on Board Or that you Are Not Taken by Sirprise by Boats from the Shore which has often ben the Case Let your Slaves be well Lookd after properly & Carefully Tended Kept in Action by Playing Upon Deck ... if Sick well Tended in ye Half Deck & by All Means Keep up Thare Spirretts & when you Cum off the Coast bring off a Full Allowance of Rice & Water for a Ten Week PaSage Upon this your Voyage Depends in a Grate Measure ... by all Means I Reacommend Industry, Frugality & dispatch which will Reacommend you to farther BuSsiness. Your Wages is Three pounds Ten Sterling per Month Three Slaves, priviledge & three % but of the Cargo of Slaves Delivered at Boston, This is all you are to have...

Chapter One—

From a letter written by Timothy Fitch,

a successful merchant in the slave trade,

to his employee Captain

Peter Quinn, dated January 12, 1760,

dateline Boston, Massachusetts

MAY 1772

"What do you remember, Phillis? What do you remember?"

They are always asking me that. As if I would tell anyone about my life before. The few good memories I have I cherish and hold fast. My people believe that if you give away your memories, you give away part of your spirit.

It was Nathaniel asking now. We were at breakfast before the rest of the family came down. "If you can remember anything about your life before, you should tell these men today," he said, looking up from the newspaper he was reading.

Today I must go to the governor's mansion. To stand before a committee of the most noble men in Boston to prove that the poetry I have written is mine.

Me. Phillis Wheatley. A nigra slave who was taken into the home of the Wheatleys as a kindness. And who responded to that kindness by doing something few well-born white women would do in this year of 1772.

Put her thoughts to paper. Write down the workings of her mind.

Now, because I had made so bold as to do such a thing, I must stand before these shining lights of the colony today and answer their questions. Had I truly written this poetry? Or stolen it from somewhere? Was I passing myself off as a lie? The mere thought of their questions made my innards turn over.

"Don't be anxious, Phillis," Nathaniel was saying.

"I'm not anxious."

"You're touching your cowrie shell. You always do that when you are anxious."

He was right. I drew my hand down from the shell that I wear on a black, velvet ribbon around my neck. My mother gave it to me when we were taken from our home. It gives me comfort when I'm distressed.

"You look very lovely in that new frock," Nathaniel said, spooning fresh fish into his mouth, "but must you wear that shell for this occasion today?"

"I always wear it," I said. "It's my good talisman."

He shrugged and went back to his reading.

I'd been bought for cowries. Sold by the people of my own land into the hands of Captain Peter Quinn for seventy-two of the lovely creamy white shells that serve as currency in the slave trade.

Nathaniel does not know this, though he knows me better than anyone. None of the Wheatleys know it. There are certain things that are just not for the telling.

"Why would these learned men wish to know of the past of a little nigra girl?" I asked.

"Don't be petulant, Phillis."

"I'm not."

"Yes, you are. It won't work with these men. They are all important and busy and are going out of their way to grant you this time today. But, to answer your question, if they consider your poetry in light of what your life was like

before,

it could work in your favor."

"I want them to consider my poetry for what it is. Not for being written by a slave."

"You're not a slave, Phillis."

There is the lie. A convenient one, of course, for everyone concerned.

"I don't see anyone waving free papers under my nose of late, Nathaniel."

"If I knew you were going to be vile this morning, I would have had you take a tray in your room. Has your position in this household ever been one of a lower order, Phillis?"

Nathaniel knows I desire my freedom. He considers it a personal affront, an insult to all his family has done for me.

"No, Nathaniel. My position in this household has always been that of a daughter," I said dutifully.

"Then don't belabor this freedom business. It's tedious."

Unless you don't have it,

I thought. "I don't mean to be ungrateful, Nathaniel. Yet..." I stopped.

"Yet you would rather be free. Is that it, Phillis?" He said the word with grievous hurt in his voice.

"Yes."

"To do what? What would you do with this precious freedom that you cannot do now?"

But I had no answer for that. For I do not know what I would do with it.

"None of us is truly free, Phillis," he said languidly, "but if you wish it so much, then I put forth to you that you will someday be like Terence. Do you recollect who Terence was?" He was playing the teacher now, a role he cherished.

I knew I must answer. I did so sullenly. "A Roman author who wrote comedies. African by birth. A slave. Freed by the fruits of his pen."

"As you will someday be. If you follow the course we have set for you. Pray that day does not come too soon. For you will regret it."

My bones chilled. But I challenged him. "How so?"

He expected to be challenged. It is the way of things with us, the way he taught me everything I know. By argument, open discourse. "Because then all this"—and he waved his fork to include the polished dining table, the sparkling silver, the shining pewter—"will be lost to you. And you to us. You thrive only under our protection, Phillis. Free, you will perish."

"Terence did not perish."

"True. But that was Rome. This is Boston." There was a twinkle in his blue eyes. He was enjoying himself.

But he was right, and I knew it. He is always right. That is the tedious thing about him.

"I just thought it might go well for you this morning if these esteemed gentlemen knew what you had been through. With the middle passage, for instance," he said.

I glared at him. He was debonair, self-assured, the only son in a well-placed family, wearing a satin and brocade waistcoat and a velvet ribbon on his queue, but his question sat ill on me. "What do

you

know of the middle passage?"

"Don't take umbrage, Phillis."

"If we're going to fight, give me fair warning, Nathaniel. I've the mettle for it. But don't pretend kindness and speak to me of such things as the middle passage."

He lowered his eyes. "So it was as bad as they say, then?"

"That depends on who is doing the saying."

"No matter. Some men on the docks."

"If they work on slavers, then they know, Nathaniel. Everything they say is true. But I have no need in me to speak of it."

He raised his cup of chocolate. "A proper answer from a proper young woman."

"I'm not a proper young woman and you know it."

"My, we're contentious this morning."

"I wasn't when I came to the table. You've made me so."

He smiled. "No, you are not a proper young woman, Phillis. No proper young woman writes poetry."

Well, he spoke no lie.

"Don't look so distressed. Proper is tedious."

"Your sister, Mary, is proper, and you think her wonderful."

"I think her tedious. And prissy and foolish."

"She loves her reverend."

"Yes, and likely the loving will kill her. Here she is being brought to bed of a child twice in one year. Such a lot is not for you, Phillis."

"What is my lot, then?"

"Grander than that ... If you succeed with these fine gentlemen this morning."

"And if I don't?"

"You will, Phillis, you will."

His words brought tears to my eyes. When all is said and done, Nathaniel always has believed in me. When I first came to this house, ten years ago, he befriended me; while his pious and prissy sister, Mary, his twin, tormented me so.

I was seven then and they were seventeen. I thought Nathaniel was a god. Or at least a roc, which is the name we give the huge birds that, in our stories, swoop down and fly away with elephants.

In his own way, Nathaniel swept down on me. And saved me. And now I hate him for it, no-account wretch that I am. In part because I have come to depend on him so.

And in part because I love him.

I love him because he is sharp, smart, and not lazy. Because he sees beneath the pious claptrap of Boston and says things we should not speak of.

Things I think all the time. I love him because there is an excitement about him that bespeaks things about to happen. Or makes them happen, I don't know which.

I love him because he had a hand in making me write my poetry.

He does not know I love him, of course. If he did, it would be the end of any discourse between us. Certainly it would be the end of me in this house. Bad enough that I write poetry. To profess love for the master's son would be unforgivable.

Soon Nathaniel will

be

the master, with Mr. Wheatley sickly with gout and about to retire. Nathaniel is buying out his father's holdings now, and running things.