Harbour (21 page)

He turned his face to the sea and the north wind grabbed him with its full power. The lighthouse at GÃ¥vasten flashed far away in the distance, and the seaâ¦

â¦

the seaâ¦

Something came away inside him. Part of what he needed fell off.

â¦

the seaâ¦

He groped for support and got hold of a branch of the apple tree. A lingering apple was shaken free and fell to the ground with a barely audible thud.

â¦

comes awayâ¦fallsâ¦

The branch gave way when he put too much weight on it, and he sank down on the grass. The branch slipped from his grasp and whipped across his cheek as it sprang back. He felt a stinging pain and fell on his back, his eyes wide open. The thing that had come away was floating around inside him and he felt ill. And weak. Weak.

The branches of the apple tree where whipping back and forth as if the tree wanted to erase the starry sky, and Simon lay there motionless, staring. The stars twinkled through the remaining leaves and the strength trickled out of Simon's limbs.

I have no strength. I'm dying.

He lay there like that for a long time waiting for the lights to go out, and he had plenty of opportunity to think. But the stars continued to shine and the wind continued to roar. He tried to move his arm, and it obeyed. His hand closed around a fallen apple and he let it rest there for a while. The exhaustion was diminishing slightly, but he was still weak.

He got to his knees and then to his feet, stood there swaying like a poplar sapling in the wind. One hand felt peculiar, and when he looked he saw that he was still holding the apple. He dropped it. He set off for his house again, his feet dragging.

Something happened.

When he eventually reached his door he peered down at the jetty. It was difficult to see in the faint light from the lighthouse and the stars, but it looked as if the boat was exactly where it should be. The stone jetty was absorbing the worst of it. Not that he would have been able to do anything, particularly not now, but it was good that he still had a boat.

He got himself inside and switched on the light, sat down at the kitchen table breathing in weak bursts, trying to get used to the idea that he was still alive. He had been convinced that he was going to die; he had even managed to reconcile himself to that conviction. To collapse beneath Anna-Greta's apple tree and be swept away by the storm. It could have been worse, much worse.

But it didn't turn out that way.

A thought had taken root in his mind during his painfully slow trek home, a suspicion. He took the matchbox out of the kitchen drawer and opened it. Despite the fact that it was as he suspected, he couldn't help gasping out loud.

The larva was grey. The skin which had been so shiny and black had shrunk and dried, acquired an ash-grey colour. Simon shook the box carefully. The larva squirmed slightly and Simon breathed out. He gathered saliva and let it fall. The larva moved when the saliva landed on it, but not much. It was weak; it seemed to be fading away.

Like me.

The storm was rattling the window panes. Simon sat there staring down into the box, trying to understand. Was it he or Spiritus that came first? Did he influence the larva, or vice versa? Who was to blameâeither of them?

Or some third party. Who influences both of us.

He looked out of the window and blinked. GÃ¥vasten lighthouse blinked back.

Communication

Anders woke up because he was freezing cold. The storm was raging around the Shack and inside the house there was a light-to-moderate wind. The curtains were billowing, and cold air swept across his face. He got up with the blanket around his shoulders and went over to the window.

The sea was in turmoil, the waves hurling themselves forward furiously in the moonlight. Stray drops were actually reaching right up to the window, which was creaking ominously under the pressure of the storm. The old windows with their secondary doubleglazing were a poor defence against the fury of nature. Plus a couple of windows were already cracked from before.

What will I do if something breaks?

He would just have to see what happened. He put the kitchen light on and drank a couple of glasses of water, lit a cigarette. The clock on the wall showed half-past two. The smoke from his cigarette whirled around in the draughts slicing through the house. He sat down at the table and tried to blow smoke rings, but without success.

Fifty or so blue beads and five white ones were pushed down in one corner of the bead tile. The white ones were in a little clump, surrounded by the blue ones. He rubbed his eyes and tried to remember when he had put them there. He had come home feeling quite tipsy, and had pushed in a few beads at random. After that he couldn't remember a thing until he lay down on the sofa and listened to the wind until he fell asleep.

The pattern formed by the blue and white beads was meaningless and not particularly attractive. He cleared his throat as the smoke formed a viscous lump there, and looked around for a knife or something similar with which he could ease the beads off. There was a pencil lying next to the tile and he picked it up before realising that it wouldn't do.

Then he caught sight of the letters.

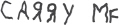

The pencil had been lying on some letters, written directly on the surface of the table with so much pressure that they had made grooves in the old wood. Anders leaned forward and read. It said:

He stared at the letters, ran his finger over the faint indentations they had made.

Carry mf?

It was as if his eyes were glued to the sprawling letters and he didn't dare to look either to the right or left. A shudder ran down his back.

There's someone here.

Someone was watching him. He tensed the muscles in his legs, swallowed hard and without warning he shot up from his chair with such speed that it fell over backwards. He looked quickly around the kitchen, in all the corners and shadows. There was no one there.

He looked out of the kitchen window, but although he cupped his hands around his eyes, the pine trees obscured the moonlight so that it was impossible to see if there was anyone out there. Anyone watching him.

He crossed his arms over his chest as if to keep his racing heart in its place. Someone had been in here and formed the letters. Presumably the same person who was watching him. He gave a start and ran over to the outside door. It wasn't locked. He opened it and saw the swing being hurled in the air, spinning around and slamming into the tree trunks. Nothing else.

He went back to the kitchen and sluiced his face with cold water, dried himself with a tea towel and tried to calm down. It didn't work. He was horribly afraid, without knowing what he was afraid of. An extra-powerful gust of wind made the house shake, and there was a creaking sound.

The next moment one of the windows in the living room shattered, and Anders screamed out loud. Glass came rattling in across the floor, and Anders kept screaming. The wind raced into the house, grabbed hold of anything that was light and loose, threw it around, whistled up the chimney, howled in every hollow and Anders howled along with it. His hair was flapping and damp air poured over him as he stood there screaming, his arms locked around his body. He didn't stop until his throat began to hurt.

His arms released their grip and he relaxed slightly, breathing slowly through his open mouth.

No one came. It's only the wind. The wind broke a window. Nothing else.

He closed the kitchen door. The wind retreated, withdrawing to the living room where Anders could hear it fighting with old newspapers and magazines. He sat down at the kitchen table and put his head in his hands. The letters were still there. The wind hadn't taken them.

He pressed his hands over his ears and closed his eyes tightly. Everything went dark red in front of his eyes, but he couldn't escape. The letters appeared in bright yellow, disappeared and were written once more on his retinas.

Suddenly he took his hands away, got up and looked around. No. The drawings weren't here. He reached the kitchen door in a couple of rapid strides, pulled it open and passed the living room without a thought for the wind that grabbed at the blanket he was wearing like a coat.

He went into the bedroom and closed the door behind him, dropped to his knees next to Maja's bed and groped around with his arm until he found what he was looking for. The plastic folder containing Maja's drawings. With shaking hands he managed to pull off the elastic band and spread the drawings out on the bed.

Most of them had no writing, and on those that did it said, âTo Mummy', âTo Daddy'.

But there was oneâ¦

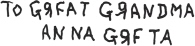

He turned over the various drawings of trees, houses and flowers to check the back of each one, and at last he found it. On the back of a drawing of four sunflowers and something that could be either a horse or a dog, Maja had written:

It had taken her ten minutes and two outbursts of rage before she was satisfied with what she had written. Earlier versions were angrily rubbed out. The drawing had been for Anna-Greta's birthday, and for some reason had never been handed over. It said, âTo Great Grandma Anna-Greta'.

The letter R was the wrong way round just as it was in the words on the table, but what made Anders press his hand against his mouth as the tears sprang to his eyes was a more unusual error: in both cases the bottom stroke of the letter E was missing.

Of course he had known all along what was written on the kitchen table. He had refused to accept it. The handwriting was exactly the same as on the drawing, and it said:

âCarry me'.

It was quarter-past three and Anders knew he wouldn't be able to sleep. The storm had abated somewhat and the sensible thing would be to try and sort out the mess in the living room, if possible board up the window somehow.

But he just didn't have the strength. He felt exhausted and wideawake at the same time, his brain working feverishly. The only thing he could do was to sit at the kitchen table twisting his fingers around each other as he looked at the message from his daughter.