Harlem Nocturne (23 page)

Authors: Farah Jasmine Griffin

In these solos, Williams is a mature artist, capable of swinging but also of playing deeply introspective music. One can hear her Harlem stride background as well as her bop present, her strong left hand and each individual finger of the right hand as she caresses the keys. There is no doubt that she is in command of her genius and her instrument. She was still without a lucrative recording deal with a major label. She was both tired and restless. But she was the consummate artist.

For some time, Glaser had been encouraging Williams to tour Europe. Now, as she found it more difficult to find work,

and was facing financial difficulties, the idea was becoming attractive. As early as 1947, Williams began to consider his idea. Many of her good friends were there, especially in Paris. Jazz singer Inez Cavanaugh was living there and seemed quite happy, in spite of being unable to find black hair-care products. Williams would pack care packages and send them overseas. For these Cavanaugh was grateful, writing, “Make[s] a cullud girl happy just to see a jar of Dixie Peach.”

On November 28, 1952, Williams attended a bon voyage celebration in her honor. The guests included jazz innovators Oscar Pettiford and Erroll Gardner. The next day she set sail on the

Queen Mary

, headed for Europe, where she planned to stay nine days. As it turned out, she would not return to New York for two years.

During her time in Europe, Williams suffered what some call a nervous breakdown. It might also have been a spiritual crisis, “a dark night of the soul.” Finding solace in Catholicism, Williams abandoned music temporarily, only to return to it at the encouragement of her spiritual mentors. In the years that followed, she devoted much of her life to addressing human suffering, especially what she witnessed in Harlem, and to exploring the deeply spiritual dimensions of the music called “jazz.” To Williams, these two projectsâone humanitarian and the other aestheticâwere one.

N

ew York beckoned, and they came. They gave it sound and substance, word and music, dance and meaning. In turn, it gave them inspiration, a community, and an audience. It contributed to each one's already strong sense of self. It gave them the world. At the end of their careers, all three were honored by the city and its institutions.

But there was something unique about the 1940s. Perhaps it was a combination of the times and the women. A woman in her twenties and thirties is usually a vessel for lifeâmost often bearing and rearing children. But sometimes, the creativity, brilliance, and energy required of mothering are available for other areas of a woman's life, particularly for creative and intellectual women. Their imagination is fertile; their stamina and concentration strong. Petry, Primus, and Williams were certainly not the only creative women living in New York, or even in Harlem. The city was teeming with them, though few acquired the fame and stature of these three.

All three experienced high points of creativity and celebrity during the early part of the decade. By decade's end, their stars had faded a little as the venues and organizations that had supported them closed or were transformed. Cultural tastes changed. The neighborhood they loved fell on hard times, and the nation they hoped to shape was still flawed. Women who had filled factories and offices during the war were asked to return home. The end of the decade saw the emergence of the Cold War, McCarthyism, and the “urban renewal” that followed in the wake of the Housing Act of 1949. Each of these developments would alter the contexts in which these women lived.

Harlem Nocturne

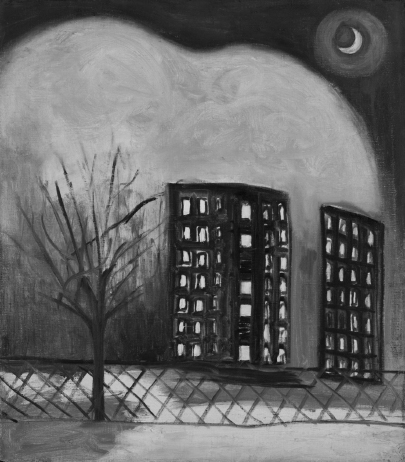

. Alice Neel. 1952. Courtesy of Estate of Alice Neel.

Painter Alice Neel, another Harlem-based artist and a contemporary of Primus, Petry, and Williams, portrayed this sense of change, closure, and nightfall in a painting entitled

Harlem Nocturne

(1952). Two high-rise apartment buildings sit on a barren landscape. Enclosed by a metal link fence and parallel to a lone, leafless tree, the buildings could be any of the modern apartment buildings one finds in Manhattan, but they most resemble the high-rise housing projects that began to sprout in poor neighborhoods. The buildings look institutional. Obvious in their absence are people. Like the leaves on the trees, they are gone from the streets. Perhaps they are inside the brightly lit apartments, but we see no evidence of them in the windows.

Harlem Nocturne

is not only Harlem at night, but Harlem after slum clearance, blight removal, and urban renewal. Harlem after “an epoch's sun declines.”

1

This is the Harlem about which Petry wrote in her last article on the area; it is the Harlem that Mary Lou Williams walked prior to her departure for Europe.

Fortunately, the story does not end here, or rather, the end marks another beginning. Harlem experienced many new

births, progressive politics did not die, and politically engaged artists would continue to answer their calling. So, too, does the sun rise again on the brilliant women of

Harlem Nocturne

.

The 1950s found Pearl Primus engaged in a variety of activities, personal and professional. She married twice, first to Yael Woll and then to Percival Borde, her collaborator and soul mate. She also gave birth to a son, Onwin. In 1959, she received a master's degree in education from New York University, and that same year she was named director of a new performing arts center in Liberia. Although her passport had been revoked in 1952, it was eventually returned, and she spent much of her time traveling throughout Africa and Europe. At the behest of the Liberian government, she choreographed

Fanga

, which would become one of her best-known dances. In 1978, she earned her PhD in dance education from New York University, received the Dance Pioneer Award from the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and incorporated her Pearl Primus Dance Language Institute. Shortly thereafter, she became a professor of ethnic studies, artist in residence, and the first chair of the Five College Dance Department, organized under the Five College Consortium among Mount Holyoke, Amherst, Hampshire, and Smith Colleges and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. In 1988, the American Dance Festival restaged her choreography for

Black Tradition in American Modern Dance

, a program seeking to preserve black dance. In 1991, President George H. W. Bush honored her with the National Medal of the Arts. The following year, the Kennedy Center held a Pearl Primus 50th Anniversary Concert.

Dance was the vehicle through which Primus expressed her intellectual and political commitments. Africa became central to these commitments as well as to Primus's growing sense of spirituality. Her devotion to the history and cultures of the continent never wavered. At the time of her death in 1994, the

New York Times

reported, “Her belief that there was material for dance in the everyday lives of black peopleâand her strong personality and early successâhad a profound influence on several generations of black choreographers and dancers, among them Donald McKayle and Alvin Ailey.”

2

McKayle and Ailey are not the only heirs of Primus's legacy. It lives on in the work of Jawole Willa Jo Zollar and her company, Urban Bush Women, and in the work of Primus's niece, Andara Koumba Rahman-Ndiaye, and her company, Drumsong African Ballet Theater (ABT). These two women and their respective companies continue two distinct but related components of Primus's artistic, intellectual, and political project. Dancer, singer, drummer, choreographer, and teacher, Rahman-Ndiaye, working in collaboration with her husband, Obara Wali Rahman-Ndiaye, founder and director of Drumsong, continues the work of her aunt by presenting the dance, history, and culture of Senegambia. Her intergenerational company features dancers, drummers, and singers young and old, male and female. Together they constitute an African-centered, spiritually driven community devoted to honoring the cultures of Africa and the diaspora. Zollar has choreographed two beautiful pieces inspired by Primus's own choreography as well as her journals and interviews, “Walking with Pearl . . . Africa Diaries” and “Walking with Pearl . . . Southern Diaries.” Zollar may be one of the most energetic and consistent of

Primus's artistic heirs. She has not only choreographed works inspired by Primus, but is also building upon some of her earlier social and political commitments.

After moving back to Old Saybrook, Ann Petry gave birth to a daughter, Elisabeth, in January 1949. She published two more novels after

The Street: A Country Place

in 1947, and

The Narrows

in 1953.

The Narrows

would be Petry's last novel, but she continued to publish short stories and children's books. For the most part she remained out of the public eye, though she continued to be a participating member of her community. She continued to have faith in the democratic process as she remained actively involved in her town's politics, serving on its Republican Town Committee and running for and winning a seat on the school board.

In the 1970s and 1980s, a bevy of young black women writers began to publish highly original works of fiction: Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Ntozake Shange, Gloria Naylor, and others would help to change the face of American literature. When Naylor, author of

The Women of Brewster Place

, was asked about her influences, she named Petry foremost among them. Petry offered an alternative to Zora Neale Hurston's “evocations” of black folk culture and to Richard Wright's masculinist urbanism. Petry hated the constant comparisons between herself and Richard Wright, but that may have been one price of renewed recognition. When establishing or creating a tradition, critics must identify the ways that books and authors speak to each other.

When Deborah McDowell, an important black feminist critic, founded and began to edit the Black Women Writers series

for Beacon Press, she selected

The Street

to be part of the series. Although academic critics were the primary reasons for the renewal of interest in Petry's work, Petry did not like academic criticism, believing it created a barrier between reader and text. She found most academic criticism “uninteresting.” Nonetheless, throughout the 1980s and 1990s, she and her work received more and more attention from critics. In 1996, in recognition of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of

The Street

, literary critic and biographer Arnold Rampersad hosted a reading at New York's Town Hall, where the acclaimed actress Alfre Woodard read selections from the novel. By the time of Petry's death in 1997, this novel was appearing on college syllabi, Petry's fiction had been republished in new editions, and she had received numerous honorary degrees. In 1992, Trinity College hosted a daylong symposium and celebration in her honor. In 1997, her

New York Times

obituary noted that Petry “took a single stretch of Harlem and brought it vividly and disturbingly to life in her acclaimed 1946 novel, âThe Street.'”

3

Mary Lou Williams returned to New York and to Harlem in December 1954. She found a church home in Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church on 142nd Street. Dizzy Gillespie introduced her to Father John Crowley, who encouraged her to return to music as a vehicle for prayer and healing, both for herself and for others. Father Anthony S. Woods and a young priest named Father Peter O'Brien also served as her spiritual mentors. O'Brien became her manager as well. Williams was baptized into the Catholic faith on May 7, 1957, by Father

Woods and confirmed the following June. She returned to performing, and she founded the Bel Canto Foundation, which helped jazz musicians with substance abuse problems by assisting with their rehabilitation. Williams also opened a number of thrift stores in Harlem and used the funds she collected to help musicians.

Though she was performing again, Williams found it more difficult to do so in nightclubs. In the 1960s, she began to compose music inspired by her new faith that was still rooted in a jazz aesthetic, including “Black Christ of the Andes” (1963), a hymn in honor of St. Martin de Porres, and “Mass for Peace,” also known as “Mary Lou's Mass” (1964). When her old friend and employer Barney Josephson opened a restaurant, the Cookery, Mary Lou convinced him to install a piano and have her play. He rented a piano, and in 1970 Williams began her residency there. Musicians came, old fans showed up, and young hipsters and college students came, too. She played there on and off until 1978. In 1977, she appeared at Carnegie Hall with the avant-garde pianist Cecil Taylor. That same year, when she was hired by Duke University, she was among the first group of African American jazz artists to obtain academic positions at major American universities. Her final recording, “Solo Recital,” recorded at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland in 1978, is a testament to her genius, her spiritual maturity, her soulfulness, and her virtuosity. She died of bladder cancer in Durham in 1981.