Harold (39 page)

ERCIA

In 1042 Earl Leofric probably held authority in Western Mercia with which his predecessors, Eadric

Streona

and Leofwine, appear to have been associated. The area he controlled certainly included a portion of the Welsh March as his brother Edwin was slain by the Welsh in 1039. It is clear that he did not control Herefordshire, which remained in other hands throughout this period. However, it seems that by 1055, if not before, Leofric controlled the rest of the Welsh border shires, as his son, Aelfgar, singled out Hereford for attack rather than oppose his father elsewhere. There is firm evidence that he controlled Worcestershire and, judging from the area governed by his successors, noted below, it seems likely that he also controlled Cheshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and possibly Leicestershire.

5

The Chronicle records in 1057 that Aelfgar succeeded to the earldom that his father had held. This indicates that his authority extended over an area similar to that of his father and his authority over Worcestershire and Warwickshire, at least, is confirmed by the sources. Again, as his successor, Edwin, inherited his authority, it seems likely that Aelfgar also held Cheshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire and possibly Leicestershire. The possibility that Aelfgar held some authority in Oxfordshire will be discussed below.

6

No source records Earl Edwin’s succession to his father, but the extent of his authority is better reported. Thus we know from Domesday Book and elsewhere that Edwin’s earldom included Cheshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and possibly Leicestershire. In addition, the account of King William’s reactions to the rebellions led by Earls Edwin and Morcar show him subduing them by constructing a castle at Warwick in 1068 and defeating their forces at Stafford the following year.

7

ESSEX

In 1042 Earl Godwine certainly controlled a large area of southern England including Kent, Sussex and the region of Wessex incorporating, certainly, Hampshire, Devon and Berkshire, possibly Surrey and Wiltshire, and perhaps Somerset, Dorset and Cornwall. The dispute at Dover in 1051 confirms Kent as part of Godwine’s earldom and the fact that he drew the support for his restoration in 1052 from Kent, Sussex and Surrey establishes his strong links with the area. The possible diminution of Godwine’s area of authority in favour of his eldest son, Swein, will be discussed below.

8

The exile of Earl Godwine in 1051 brought his earldom into King Edward’s hands and the latter subsequently granted the shires of Somerset, Dorset, Devon and Cornwall to his kinsman Earl Odda. On his restoration in 1052 Earl Godwine was returned his earldom ‘as fully and completely’ as he had held it before. This seems to imply that Earl Odda lost the south-western shires, which were presumably returned to Earl Godwine and were certainly held by his successor Harold, though it is just possible that the latter may have gained them after Earl Odda’s death in 1056.

9

In 1053 Harold succeeded to his father’s earldom, which certainly included Kent, Surrey, Hampshire, Berkshire, Dorset, Somerset and Devon and probably Sussex, Wiltshire and Cornwall. This earldom was extended in 1057 on the death of Earl Ralph, when Harold added the shires of Gloucester and Hereford to those covered by his authority. It appears that Harold retained this entire earldom in his own hands until he became king, when it provided him with a secure base for his rule.

10

This discussion of the three main earldoms indicates a fairly clear pattern of succession to these earldoms, with only minor alterations or amendments. This leaves only a fairly narrow region from East Anglia to the Severn estuary and the Welsh border available for the new earls created by Edward. Allocating the few shires in this region to the new earls in a way which matches the established facts is a more difficult task. In view of the sparse evidence, the suggested outline that follows must remain just that, although it may provide a useful framework for the political structure of Edward’s England.

HE

O

THER

E

ARLDOMS

King Edward appointed three new earls in the years immediately following his succession, namely Swein in 1043 and Beorn and Harold in 1045. Earl Swein certainly held Herefordshire from the start, as witness his invasion of Wales in 1046 and subsequent seizure of the abbess of Leominster. As John of Worcester mentions, it seems likely that Swein also controlled Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire. Although John also says Swein held Somerset and Berkshire in 1051, these must have been surrendered to him at a later date by Earl Godwine, because the latter held Berkshire between 1045 and 1048. In 1045 Swein may possibly have held Buckinghamshire and Middlesex instead. At this time Earl Beorn certainly held Hertfordshire, probably Huntingdonshire, and perhaps also Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire and Northampton-shire. Earl Harold certainly held Norfolk and Suffolk, and probably also Essex.

11

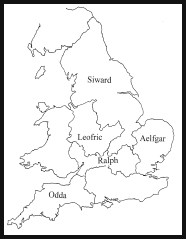

The earldoms, 1045. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, 1050. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, late 1051. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, late 1052. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, 1056. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, 1060. (© Ian W. Walker)

The earldoms, end 1065. (© Ian W. Walker)

The exile of Earl Swein in 1047 disrupted this arrangement and authority over his shires was probably temporarily shared between Harold and Beorn, as implied by one of the Chronicle reports of Swein’s return in 1049. Thereafter, the murder of Beorn, the renewed exile and subsequent restoration of Swein, and the appointment of King Edward’s nephew, Ralph, to an earldom in 1050 produced a new pattern of earldoms by 1051. The exact process involved in this transformation is obscure, but some suggestions can be offered.

12

According to John of Worcester, in 1051 Earl Harold held not only Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex, but also Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire. He presumably gained the latter shires after the murder of Beorn as compensation for his surrender either to Swein or to Ralph of his share of Swein’s former earldom, perhaps Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire. Also according to John of Worcester, Swein was in control of Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Somerset and Berkshire in 1051. This area consisted of Herefordshire, recovered from Earl Ralph who had established his Frenchmen in the shire, and Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, recovered from either Earl Ralph or Earl Harold. However, it also included Somerset and Berkshire, probably donated by Earl Godwine himself in order to persuade King Edward and the other earls that Swein’s restoration would be relatively painless. If these assumptions are correct, the earldom held by Ralph can now be deduced, by a process of elimination, as consisting probably of the remaining shires of Middlesex, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire. The Chronicle makes it clear that in spite of his loss of Herefordshire, on Swein’s return Ralph still held territory from which he raised troops to support King Edward.

13

The exile of the Godwine family in 1051 meant further upheavals, with both Swein and Harold deprived of their earldoms. Earl Harold’s earldom was granted to Aelfgar, son of Leofric, who certainly controlled Norfolk and Suffolk, and probably Essex and Cambridgeshire, though not apparently Huntingdonshire. Earl Ralph resumed control of Herefordshire, and probably Oxfordshire, from Swein and possibly gained Gloucestershire, though he appears to have surrendered Northamptonshire. The two shires lost by these men apparently passed to Earl Siward, perhaps as a reward for supporting King Edward in the recent crisis.

14