Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (23 page)

Read Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh Online

Authors: Joyce Tyldesley

Tags: #History, #Africa, #General, #World, #Ancient

5

War and Peace

To look upon her was more beautiful than anything; her splendour and her form were divine; she was a maiden, beautiful and blooming.

1

Hatchepsut lived before the full-length looking glass had been invented. She could examine her features in the highly polished metal ‘see-face’ which, carried in a special mirror-bag designed to be slung over the shoulder, was an essential accessory for every upper-class matron, but she was forced to turn to others for confirmation of her overall beauty. We should perhaps not be too surprised to find that her loyal and prudent courtiers dutifully praised their new king as the most attractive woman in Egypt. Her own words, quoted above, betray a rather touching pride in her own appearance – clearly these things mattered to even the highest-ranking Egyptian female – while incidental finds of her most intimate possessions, such as an alabaster eye make-up container, with integral bronze applicator, engraved with Hatchepsut's early title of ‘God's Wife’, or a pair of golden bracelets engraved with Hatchepsut's name but recovered from the tomb of a concubine of Tuthmosis III, serve as a reminder that Hatchepsut, the semi-divine king of Egypt, was also a real flesh-and-blood woman.

We have no contemporary, unbiased, description or illustration of Hatchepsut, although we can assume that, in common with most upper-class Egyptian women of her time, she was relatively petite with a light brown skin, a relatively narrow skull, dark brown eyes and wavy dark brown or black hair. She may, in fact, have chosen to be completely bald. Throughout the New Kingdom it was common for both the male and the female élite to shave their heads; this was a practical response to the heat and dust of the Egyptian climate, and the false-hair industry flourished as elaborate wigs were

de rigueur

for more formal occasions. The king's smooth golden body was perfumed with all the exotic oils of Egypt:

His majesty herself put with her own hands oil of ani on all her limbs. Her fragrance was like a divine breath, her scent reached as far as the land of Punt; her skin is made of gold, it shines like the stars…

2

Hatchepsut's surviving statues, although always highly idealized, provide us with a more specific set of clues to her actual appearance. The new king evidently had a slender build with an attractive oval face, a high forehead, almond-shaped eyes, a delicate pointed chin – which in some instances is almost a receding chin – and a rather prominent nose which adds character to her otherwise rather bland expression. Towards the beginning of her reign her features show a certain feminine softness, a possible indication of her youth; later statues show her sterner, somehow harder, and more the embodiment of the traditional pharaoh. To some sympathetic observers her face betrays outward signs of her inner struggle: ‘… worn, strong, thoughtful and masculine but with something moving and pathetic in the expression’.

3

To Hayes, describing a red granite statue from Deir el-Bahri, the king displays ‘… a handsome face, but not one distinguished by the qualities of honesty and generosity’.

4

There is a general family resemblance between the statuary of Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III – large noses obviously ran in the Tuthmoside family – which is not necessarily the result of both kings being sculpted by the same workshop. This can present problems for the unwary student of egyptology, and entire learned papers have been devoted to the question of exactly which monarch is represented by a particular statue.

From the time of her coronation onwards Hatchepsut no longer wished to be recognized as a beautiful or indeed even a conventional woman. She chose instead to abandon the customary woman's sheath dress and queen's crown and be depicted wearing the traditional royal regalia of short kilt, crown or head-cloth, broad collar and false beard. Very occasionally, towards the beginning of her reign, she took the form of a woman dressed in king's clothing; two seated limestone statues recovered from Deir el-Bahri show her wearing the typical king's headcloth and kilt, but with a rounded, almost girlish face, no false beard and a slight, obviously feminine body with an indented waist and unmistakable breasts (see, for example, Plate

5

).

5

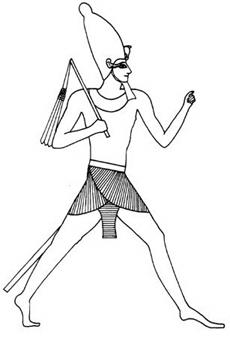

More often, however, she was shown not only with male clothing and accessories but performing male actions and with the body of a man (Plates

8

,

9

and

Fig. 5.1 Hatchepsut as a man

10). When depicted as a child at the Deir el-Bahri temple, she was presented as a naked boy with unmistakable male genitalia. Her soul, or Ka, was an equally obvious naked boy. To any observer unfamiliar with Egyptian art-history and unable to read hieroglyphic inscriptions, the female queen had successfully transformed herself into a male king. At first sight the explanation for this transvestism seems simple:

The Egyptians were averse to the throne being occupied by a woman, otherwise Hatchepsut would not have been obliged to assume the garb of a man; she would not have disguised her sex under male attire, not omitting the beard… How strong this feeling was in Hatchepsut's own time is shown by the fact that she never dared to disregard it in her sculptures, where she never appears as a woman.

6

To dismiss Hatchepsut's new appearance as a naive attempt to pose or pass herself off as a man

7

in order to fool her subjects is, however, to

underestimate both the intelligence of the new king and her supporters and the sophistication of Egyptian artistic thought. It is perfectly possible that the vast majority of the population, illiterate, uneducated and politically unaware, were indeed confused over the gender of their new ruler, and Hatchepsut may well have wished to encourage their confusion; if her people felt more secure under a male king, then so be it. However, the lower classes were to a large extent unimportant. There was no Egyptian tradition of popular political activity and the peasants had absolutely no say in the government of their country. Indeed, Egypt was never regarded as ‘their country’; everyone knew that the entire land belonged to the king and the gods. Those who did matter were the male élite and the gods, and both of these were already fully aware of Hatchepsut's sex.

Hatchepsut, former God's Wife and mother of the Princess Neferure, was widely known to be a woman. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that she suddenly came out as a transsexual, a transvestite or a lesbian, and the fact that she retained her female name and continued to use feminine word forms in many of her inscriptions suggests that she did not see herself as wholly, or even partially, male. Although we have absolutely no idea how the new king dressed in private, we should not necessarily assume that she invariably wore a man's kilt and false beard.

Accusations of ‘deviant personality and behaviour… [and] abnormal psychology’,

8

levelled by those who have attempted to psychoanalyse Hatchepsut long after her death, are generally lacking any supporting evidence. At least one modern medical expert has attempted to link this perceived ‘deviant’ behaviour with Hatchepsut's devotion to her father:

... Hatchepsut, from her early years, as exemplified by her apparent identification with her father, had a strong ‘masculine protest’ (to use Adler's term), with a pathological drive towards actual male impersonation… The difficulty with her marriage partners

[sic] might

indicate a maladjustment in hetero-sexuality. The fact that she had children

[sic]

does not obviate such a maladjustment.

9

However, such analyses, based on the scanty surviving evidence, betray a profound lack of understanding of the nature of Egyptian kingship.

Similarly, it would be wrong to dismiss these male images as mere propaganda. They were, of course, intended to convey a message, but so were all the other Egyptian royal portraits from the start of the Old

Kingdom onwards. None of the images of the pharaohs was entirely faithful to their original, but nor were they intended to be. They were designed instead to convey selected aspects of kingship popular at a particular time. Therefore we find that the kings of the Old Kingdom are generally shown as the remote embodiment of semi-divine authority, the rulers of the Middle Kingdom appear more careworn as they struggle with the burdens of office and the pharaohs of the New Kingdom have acquired a new confidence and security in their role. Conformity was always very important and physical imperfections were generally ignored, to the extent that the 19th Dynasty King Siptah is consistently portrayed as a healthy young man even though we know from his mummified body that he had a deformed foot. The same rule of conformity applied to queens, so we find that the unfortunately buck-toothed Queens Tetisheri and Ahmose Nefertari are never depicted as anything other than conventionally beautiful. If a royal statue or painted portrait happened to look like its subject, so much the better. If not, the all-important engraving of the name would prevent any confusion as the name defined the image. Indeed, it was always possible to alter the subject of a portrait or statue by leaving the features untouched and simply changing its inscription.

Hatchepsut's assumption of power had left her with several unique problems. There was no established Egyptian precedent for a female king or queen regnant and, although there was no specific law prohibiting female rulers – indeed Manetho preserves the name of a King Binothris of the 2nd Dynasty during whose reign ‘it was decided that women might hold kingly office’ - this was purely a theoretical concession. It was generally acknowledged that all pharaohs would be men. This was in full agreement with the Egyptian artistic convention of the pale woman as the private or indoor worker, the bronzed man as the more prominent public figure. Hatchepsut, as a female king, therefore had to make her own rules. She knew that in order to maintain her hold on the throne she needed to present herself before her gods and her present and future subjects as a true Egyptian king in all respects. Furthermore, she needed to make a sharp and immediately obvious distinction between her former position as queen regent and her new role as pharaoh. The change of dress was a clear sign of her altered state. When Marina Warner writes of Joan of Arc, history's best recognized cross-dresser, she could well be describing Hatchepsut:

Through her transvestism, she abrogated the destiny of womankind. She could thereby transcend her sex; she could set herself apart and usurp the privileges of the male and his claims to superiority. At the same time, by never pretending to be other than a woman and a maid, she was usurping a man's function but shaking off the trammels of his sex altogether to occupy a different third order, neither male nor female, but unearthly…

10

Both these women chose to shun conventional female dress in order to challenge the way that their societies perceived them. However, there are clear differences between the two cases. Joan wished to be seen as neither a woman nor a man, but as an androgynous virgin. By taking the (surely unnecessary) decision to adopt male garb at all times, not just on the field of battle where it could be justified on the grounds of practicality, she was making a less than subtle statement about the subordinate role assigned to those who wore female dress. Unfortunately, in choosing to make this statement she was not only flouting convention but laying herself open to the charges of unseemly, unfeminine behaviour which were eventually to lead to her death. Her cropped hair and her transvestism horrified her contemporaries. Cross-dressing, generally perceived as a threat to ordered society, was in fact specifically prohibited by the Old Testament: