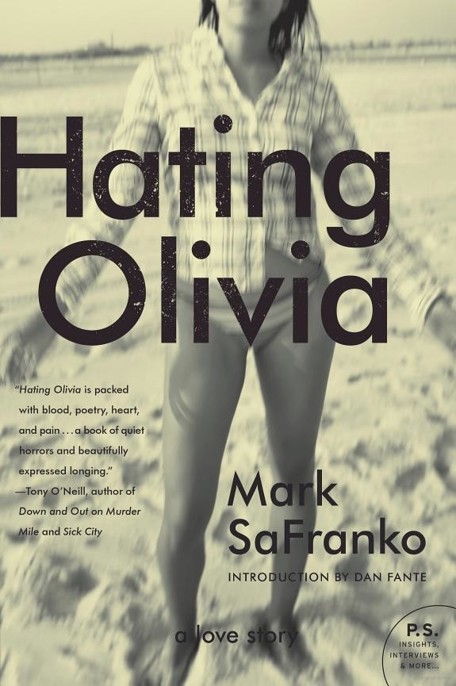

Hating Olivia: A Love Story

Hating

Olivia

a

love

story

Mark SaFranko

To P.G., for staying the course

Contents

P.S. Ideas, interviews & More … *

I am a fan of marathon runners and soccer players and guys who can go ten rounds with the champ and still manage to finish on their feet. I’m also a great admirer of Mark SaFranko’s work and have been for years.

As a writer he’s the most tenacious son of a bitch I know. Because we share the same occupation and many of the same emotions I can tell you that there are days when I’d rather chew lightbulb glass than strap myself to a computer keyboard. Not SaFranko. Compared to Mark SaFranko, I’m Tiny Tim. A novice and a flyweight.

Listen to these statistics: A hundred short stories, fifty of them already in print. A box full of poetry and essays. And ten complete novels, eight of them yet to hit the bookshelves. A dozen plays, some produced in New York and others staged in Ireland. SaFranko writes songs too, a hundred and fifty so far.

I know why I write. I write because I must. I cannot stop. I’m driven by rage and insanity and crushing ambition. Mark SaFranko scares people like me. I believe the guy would rather write than breathe. I envy his talent and commitment.

Now comes

Hating Olivia,

my favorite piece of work by the author. It is a story of love and human addiction. Here the scenes

between Max and his lady love are open heart surgery done with an ax. If you’re a Henry Miller or Bukowski fan then

Hating Olivia

is fresh meat, a gift tied together with a bloodstained bow. This is the kind of book—the kind of memoir—that must have been lived first. Survived. So strap yourself in. It’s time for a real treat.

D

AN

F

ANTE

I suffered like the most foolish of fools.

—PHILIPPE DJIAN,

37,2° le matin

In the end, one experiences only one’s self.

—NIETZSCHE

The war was over. I’d managed to avoid it, but it didn’t mean a thing. Since that time—when I wasn’t on the dole or living off food stamps—I’d worked every job under the sun: factory hand, chauffeur, reporter, bank clerk. I hadn’t done any whack-ward time, but members of my immediate and extended family had. Major depression. Bizarre phobias. Alcoholism. Shock treatments. Suicide. All of which worried me—genetics are everything. For months at a clip I wandered all over the country. The parade of forgettable days that made up the long, hazy years always seemed to be a matter of struggling to keep my head above water, and a roof over it. It was nothing much of a life.

After the sixties the world had gone to sleep again. The blue-collar suburbs were a drag, but unless you were a millionaire or willing to shack up with three or four other people you couldn’t stand or would come to hate in a short time, Manhattan was out of the question. I was neither. That left me out in Jersey, holed up in the attic of a boardinghouse on sedate Park Street in the city of Montfleur at a rent of fifteen bucks per week, excluding telephone charges.

My room was a two-by-four number with a slanting roof that collided with my head a dozen times a day. In the jake were half

a refrigerator and a bathtub—not even a shower. There was something else—cockroaches. Lots of them. The black dude next door, a short-order cook by the name of Benny, shared the facilities with me, including the cockroaches. Benny was quiet and not there most of the time, which was okay by me. My window overlooked the train station. It seemed that every other week there was a suicide on the tracks that transported the commuters into the city. I often wondered if or when I would be next.

The landlords were an elderly couple by the name of Trowbridge. Lou, a bag of bones with glasses, happened to be a painter of uncommon talent. His nudes and landscapes decorated every square inch of the faded yellow walls. It looked to me as if he’d set out to become some kind of Sisley, or Francis Bacon even, but for whatever mysterious reason he’d fallen short of the mark, like most of us do. Lately he’d taken to carving fantastic totem poles of all styles and dimensions, an idea he’d picked up while visiting his son, an army officer stationed in Alaska. But whether from lack of business sense or sheer bad luck, the poor guy never sold a thing. A regular sad sack, he wore his defeat on his sleeve. Whenever I bumped into Lou in the hallways I could hardly coax two words out of him. He never even talked back when his wife chewed him out for one of his numerous peccadilloes. “How many times have I told you to keep the back door shut so the

cat

doesn’t get out? Lou—how could you be so

stupid!

Now who’s going to chase that beast all over the neighborhood? Well—what’s your excuse? Nothing? Cat got your

tongue?

Oh, for heaven’s sake! What was I thinking when I married such a simp?” It was brutal to witness.

Myself, I didn’t mind Caroline Trowbridge. Despite my gig on the loading platform, I was forever in arrears with the rent and she never said a word about it. Since she was a gimp and had

trouble getting around, she sat in the parlor all day long with her ear pinned to the antique radio. Aside from the problem of her husband, she seemed content with her Puccini and Mahler and Mozart. Whenever I passed en route to my cell, she had a joke for me.

“Max, you wouldn’t

believe

what that idiot husband of mine did today … !”

As I climbed the stairs listening to her tirade, I’d catch the man of the house cowering in the shadows. We’d nod at each other, both of us a little embarrassed.

I couldn’t say that I knew which end was up, either. One day I pulled the number of an astrologer off the announcement board at a secondhand bookstore in Chelsea. I dialed it that evening and set an appointment for the following week. Before she could cast my horoscope, she needed the date, time, and place of my birth.

“December 23, 1950, at seven eighteen

P.M.,

Trenton, New Jersey…. ” I remembered the information from the official hospital record, which my mother had passed on to me years before.

No matter what, I figured, things couldn’t get much worse. I was smarting over the bloody breakup of an affair I’d been carrying on with the wife of an up-and-coming young attorney in the county prosecutor’s office. Months later, I still couldn’t get her out of my mind. Our dates had consisted of furtive meetings in a practice room in the music department at the college where she taught American literature. While trying to make do on the piano bench, Lynn swore to me that she was going to leave her husband. But beyond fucking her, I didn’t quite know what I’d do with her if that actually happened, since I didn’t have two nickels to rub together and she was used to some of the finer things. Once she came up to my garret and had a good look at the sagging mattress and rotting carpet, she backed off. She could see

the invisible writing on those flaking walls, all right. A part-time musician. An aspiring writer. A truck-loading bum who liked to read books and listen to obscure records—thanks, but no thanks.

Still and all, Lynn haunted my dreams even months later. What made the loss unbearable was her beauty. I’d always had an eye for beauty—fool that I was, I believed that it counted for something. Like a beggar who covets the palace of the kingdom, I wanted what I couldn’t have. But I was tired of coveting the unattainable.

Most of the time when I wasn’t stuffing the ass-end of a semi I lay around and read—Conrad … Tolstoy … Hamsun … Henry Miller … Sartre … Camus … Hesse … the Zen masters … Nietzsche … Céline … whoever and whatever I could get my hands on, so long as they held a certain appeal for the outcast. I smoked cigarettes by the carton. I masturbated compulsively over the glossy centerfolds in

Playboy

and

Penthouse

and

Club International.

I wrote songs on the guitar. When I had a few bucks to spare I hit the bars and nightclubs.

The day of my celestial appointment arrived. I rode a bus into the Port Authority and jumped the empty A train to Brooklyn Heights. After wandering around in circles for a half hour, I finally located Mrs. London’s brownstone.

“You’re late,” she announced. It sounded like an accusation.

She was full and curvy and bleached blonde and at one time she must have been attractive. But she was beyond that stage now.

I apologized for keeping her waiting. She showed me into the parlor, an airy space decorated with birdcages and stuffed furniture and expensive-looking collectibles and souvenirs, all suffused with that singular, muted Brooklyn light. It struck me that Mrs. London had some change to spare.

We sat at a large, circular oak table. She pulled my hand-drawn

chart out of a folder and positioned it in front of herself. Catching a glimpse of the abstruse squiggles, I was all set to hear how my life was about to take a turn for the better, maybe even a spectacular leap forward that would result in fulfillment, prosperity, fame, and maybe even a little money, though I never gave a damn about that; at the very least a few beautiful, adoring women who wouldn’t put me through the trials of Job.

I lit a cigarette and waited while Mrs. London gathered her thoughts. I glanced at her fingertips, which had been painted with scarlet nail polish, then at her tits, which bulged against her crepe sundress. My cock stirred in my jeans.

“Ah.

Now

I see the problem. You’re under a curse for the next five years, Mister Max.”

“What?”

“I don’t mean to alarm you, but you’re about to enter the most difficult period of the thirty-year cycle of Saturn. Some call it the ‘obscure’ period. The ringed planet—harbinger of fate and destiny—is about to cross into your tropical ascendant.”

Bull flop. “You must have gotten something wrong,” I protested.

She pointed at the southeastern quadrant of the circle.

“Right here. You will undergo many severe trials. It won’t be easy. At times you’ll think you might not make it. You’re going to have to come to grips with yourself. You’ll have to sink all the way down to the bottom before finding your way out of the black hole. Prepare yourself for the long, dark night of the soul.”

I had no interest in sinking to the bottom of anything. Shit—wasn’t I already there?

I was speechless. I didn’t believe a word of it—this stuff was all mumbo jumbo. What made me think it was anything different?

I lit another smoke. “Any chance you’re wrong?”

“It’s possible. Anything is possible. But it’s not likely. Only the masters have the power to overcome the influence of the planets. Think of Paramahansa Yogananda, or Krishnamurti. And even they had their share of troubles.”

A telephone rang somewhere. Mrs. London got up from the table.

“Be right back.”

I could make out her ass jiggling beneath the crepe as she walked toward the back of the apartment. It was a very nice ass. It disappeared into another room.

If she was a Mrs., where was her husband? The phone stopped ringing. “Oh, hello, Donald…. I’m with someone now, but let me see if I can give you a few minutes…. ”

Palm over the mouthpiece, Mrs. London popped her head out.

“I have to take this. You don’t mind waiting?”

I shook my head. Where the hell did I have to be? She slid the door half shut, but I could still see part of her as she sat at her desk back there. Her bare leg was sticking out from her bunched-up dress, and the line of her panties was visible beneath the flimsy material. I could still hear her voice, too. She went on about where Mars was in the heavens today, and how Uranus was afflicting Donald’s Mercury and that was causing whatever problems he was having.