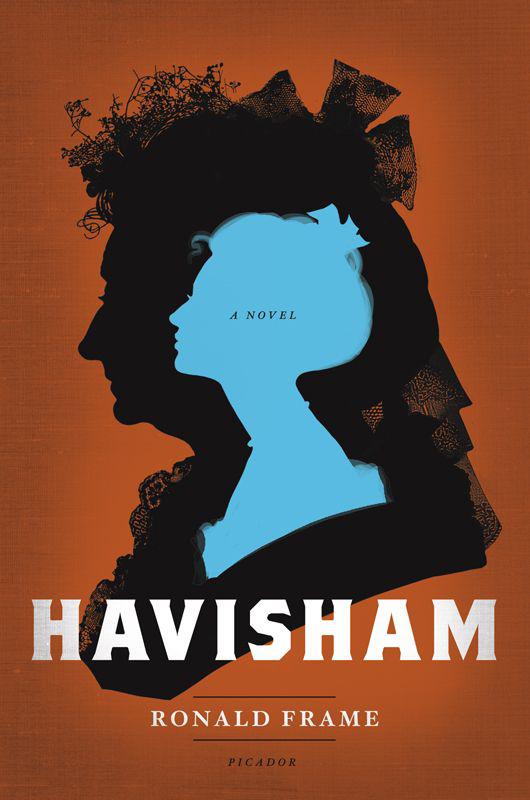

Havisham: A Novel

Authors: Ronald Frame

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

I.M.

Alexander Donaldson Frame

1922–2011

C

ONTENTS

Love is in the one who loves,

not in the one who is loved.

Plato

P

ROLOGUE

Four loud blows on the front door.

I stood waiting at the foot of the staircase as the door was opened.

The light from the candles fell upon their faces. Mr Jaggers’s, large and London-pale and mapped with a blue afternoon beard. A nursemaid’s, pink with excitement after listening on the journey down to Mr Jaggers’s discreet account of me – my wealth, my eccentric mode of life, my famous pride and prickliness.

And the third face. The child’s. She was standing a few paces behind the nursemaid; she was keeping back, but leaned over sharply to see between the two adults. She looked forward, into the house, across the hall’s black and white floor tiles.

When she was brought inside, I studied her, from my vantage-point on the second tread. Her complexion was a little tawny, as I had been led to expect. She had raven hair, which was more of the gypsy in her, but her eyes were blue, from the English father.

Blue, silvery-blue, and wide open, staring up at me. At where I stood, wearing the wedding dress I should have been married in.

I lifted my hand from the banister rail and moved to the step beneath.

Immediately the child turned away. She raised her shoulder as if to protect herself, and hid behind the nursemaid’s skirts. The woman smiled a nervous apology.

I retreated, one step up, then another.

‘Too much light,’ I said. ‘That’s all.’

The child’s eyes rested on my bride’s slippers. White satin originally, but soiled after these many months of wear.

‘The light dazzles her,’ I said. ‘She will adjust. She only needs to get her bearings.’

I

Y

OUNG

C

ATHERINE

O

NE

I killed my mother.

I had turned round in the womb, and the surgeon needed to cut her open to let me out. He couldn’t staunch her, and by the end of that evening she had bled to death.

* * *

My father draped the public rooms of Satis House in dust sheets. The chandeliers were left in situ, but wrapped in calico bags. The shutters were closed completely across some windows, and part-drawn at others.

My first days were lived out in a hush of respectfully lowered voices as a procession of folk came to offer their condolences.

My eyes became accustomed to the half-light.

* * *

One evening several new candles were set in one of the chandeliers. My mother’s clavecin was uncovered, and someone played it again – notwithstanding that it was out of tune – and that was the point at which the house stopped being a sepulchre and was slowly brought back to life.

* * *

It was the first word I remember

seeing

.

HAVISHAM.

Painted in green letters on the sooty brick of the brewhouse wall.

Fat letters. Each one had its own character.

Comfortable spreading ‘H’. Angular, proud ‘A’. Welcoming, open ‘V’. The unforthcoming sentinel ‘I’. ‘S’, a show-off, not altogether to be trusted. The squat and briefly indecisive, then reassuring ‘M’.

The name was up there even in the dark. In the morning it was the first thing I would look for from the house windows, to check that the wind hadn’t made off with our identity in the night or the slanting estuary rain washed the brickwork clean.

* * *

Jehosophat Havisham, otherwise known as Joseph Havisham, son of Matthias.

Havisham’s was the largest of several brewers in the town. Over the years we had bought out a number of smaller breweries and their outlets, but my father had preferred to concentrate production in our own (extended) works. He continued

his

father’s programme of tying in the vending sites, acquiring ownership outright or making loans to the publicans who stocked our beer.

Everyone in North Kent knew who we were. Approaching the town on the London road, the eye was drawn first to the tower of the cathedral and then, some moments later, to the name HAVISHAM so boldly stated on the old brick.

We were to be found on Crow Lane.

The brewery was on one side of the big cobbled yard, and our home on the other.

Satis House was Elizabethan, and took the shape of an E, with later addings-on. The maids would play a game, counting in their heads the rooms they had to clean, and never agreeing on a total: between twenty-five and thirty.

Once the famous Pepys had strolled by, and ventured into the Cherry Garden. There he came upon a doltish shopkeeper and his pretty daughter, and the great man ‘did kiss her’.

My father slept in the King’s Room, which was the chamber provided for Charles II following his sojourn in France, in 1660. The staircase had been made broader to accommodate the Merry Monarch as his manservants manoeuvred him upstairs and down. A second, steeper flight was built behind for the servants.

* * *

I grew up with the rich aroma of hops and the potent fumes from the fermenting rooms in my nostrils, filling my head until I failed to notice. I must have been in a state of perpetual mild intoxication.

I heard, but came not to hear, the din of the place. Casks being rolled across the cobbles, chaff-cutting, bottle-washing, racking, wood being tossed into the kiln fires. Carts rumbled in and out all day long.

The labourers had Herculean muscles. Unloading the sacks of malt and raising them on creaky pulleys; mashing the ground malt; slopping out the containers and vats; drawing into butts; pounding the extraneous yeast; always rolling those barrels from the brewhouse to the storehouse, and loading them on to the drays.

Heat, flames, steam, the dust clouds from the hops, the heady atmosphere of fermentation and money being made.

* * *

I was told by my father that the brewery was a parlous place for a little girl, and I should keep my distance. The hoists, the traps, those carts passing in and out; the horses were chosen for their strength, not their sensitivity, but every now and then one would be overcome with equine despair and make a bid for freedom, endangering itself and anyone in its path.

The brewhouse was only silent at night, and even then I heard the watchmen whistling to keep up their spirits in that gaunt and eerily echoing edifice, and the dogs for want of adventure barking at phantom intruders. The first brew-hands were there by five in the morning, sun-up, and the last left seventeen hours later, a couple of hours short of midnight.

I woke, and fell asleep, to the clopping of shod hooves, the whinnying of overworked carthorses.

* * *

‘It’s a dangerous place, miss,’ my nursemaids would repeat.

My father insisted. ‘Too many hazards for you to go running about.’

But should I ever complain about the noise, or the smell of hops or dropped dung, his response was immediate: this was our livelihood/if it was good enough for my grandfather/you’ll simply have to put up with it, won’t you, missy. So I learned not to comment, and if I was distracted from my lessons or my handiwork or my day-dreaming, I moved across to the garden side of the house. Out of doors, in the garden, the sounds would follow me, but there were flowers and trees to look at, and the wide Medway sky to traverse with my thoughts.

* * *

Sometimes I would see a man or a woman reeling drunk out of a pub, or I’d hear the singing and cursing of regulars deep in their cups.

That, too, was a part of who we Havishams were. But I would be hurried past by whoever was holding my hand, as if they had been issued with orders: the child isn’t to linger thereabouts, d’you understand. So we negotiated those obstacles double-quick, taking to side alleys if need be, to remove ourselves to somewhere more salubrious, while the rollicking voices sounded after us – but not their owners, thankfully grounded in a stupor.

T

WO

At an upstairs window, in Toad Lane, a bald-headed doll craned forward. One eyelid was closed, so that the doll appeared to be winking. It knew a secret or two.

* * *

In Feathers Lane lived a man who pickled and preserved for a trade. In

his

window he displayed some of his wares.

There in one dusty jar a long-dead lizard floated, with its jaws open and the tiny serrations of teeth visible. In another, three frogs had been frozen eternally as they danced, legs trailing elegantly behind them. Next to that was a rolled bluish tongue of something or other.

In the largest jar a two-headed object with one body was suspended, and I somehow realised – before Ruth confirmed it for me – that these were the beginnings of people: two embryos that had grown into one.

The window horrified me, but – just as much – I was fascinated by it. On the occasions when I could persuade Ruth to take me into town or home again that way, I felt a mixture of cold shivers and impatience to reach the grimy bow-fronted window where I had to raise myself on tiptoe to see in.

* * *

I thought – was it possible? – that through the slightly bitter citrus fragrance of pomander I could smell further back, I could catch my mother’s sweet perfume and powder on the clothes stored flat in the press, years after she had last worn them.

* * *

I didn’t even know where my mother was buried.

‘Far off,’ my father said. ‘In a village churchyard. Under shade.’

I asked if we might go.

‘Your mother doesn’t need us now.’

‘Don’t we need

her

?’

‘Some things belong to the past.’

His face carried the pain it always did when I brought up the subject of my mother. His eyes became fixed, pebble-like, as if he were defying tears. I sometimes thought that in the process he was trying to convince himself he didn’t like

me

very much.