He Wanted the Moon (5 page)

Read He Wanted the Moon Online

Authors: Mimi Baird,Eve Claxton

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Bipolar Disorder, #Medical

Soon after reaching my room, a type of treatment known as “constant restraint” was put into effect. I do not recall having done anything violent or uncooperative, and the nurses on the ward told me later that I had given ideal cooperation. Yet for some reason, unknown to me then and unknown to me now, I was subjected to the most exhausting, the most painful and barbaric treatment which I can conceive of in this modern age.

CHAPTER FOUR

Westborough State Hospital, 1944

The patient was very excited. He was in an over-talkative and overactive condition. He required restraint, resisted with vigor, and with his great strength, this was difficult. He destroyed a great number of restraint sheets.

THE constant restraint procedure consisted in maintaining alternation between straightjackets and cold packs.

“Take off your clothes!” Tiny shouted.

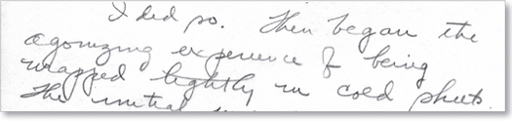

I did so.

“Lie down on this bed!” he yelled again in a needlessly coarse and antagonistic voice.

I did so.

Then began the agonizing experience of being wrapped tightly in cold sheets soaked in ice water that were folded according to various patterns and laid across the bed over a rubber mattress. The initial impact of these ice-cold sheets on the spine is pure pain. Every additional contact with cold sheets as they are wrapped around the body brings chills

and continued discomfort. First the arms are bound tightly to one’s sides and then sheets are stretched in several layers across the shoulders, body, and legs, creating a trap that permits very little motion. Large safety pins are used here and there at strategic points to secure fixation. The process of wrapping Egyptian mummies must be similar. It’s a rough business and the sense of complete immobility is uncomfortable bordering upon terrifying. Any normal individual would suffer from the feeling of being held so tightly. The manic patient—with his constant impulse toward over-activity of mind and body—suffers many times more than the normal individual might.

Restriction of motion is not the only source of pain. After the sheet wrapping and safety-pin-transfixing has been completed, transverse binders then bind one down further—across the chest, hips and legs. These are run across the body, beneath the steel bars at the sides of the bed, and back across the body, then pulled very tightly by the combined strength of two men, one working from each side. One attendant on the right, for example, will put his knee on your right shoulder and then holding the cross binder, will pull upward while pressing your shoulder down. The binder slips around the side bar of the bed and the sheet feels compressed. This attendant then holds the binder securely while the attendant across from him repeats the process. This is done by each of the attendants several times. The ends of the binders are placed across the chest and pressed down with enormous and powerful safety pins. The same procedure is repeated for hips and

legs. Finally, one or two blankets and a sheet are placed over the wrapped body and a pillow under the head.

Everyone leaves the room. The door is locked. The shock of sudden coldness rakes the body with chills. Before long this deep sense of coldness begins to wear off and the body becomes heated. This heat quickly heats up the wet sheets, and the warm blankets prevent the escape of the heat. Soon, one feels hot and feverish. A great sense of restlessness comes over one.

From the beginning of each pack, the calf muscles feel uncomfortable, and no effort to change position will relieve this discomfort completely. Pulling the toes up, and then pushing them down, lessens the discomfort. One perspires profusely due to sheet insulation, retained body heat and violent physical exercise. As a result salt is lost and muscle cramps develop (as is well recognized in industries where workers labor in a hot atmosphere). In my own case, these cramps were noticed chiefly in the calf muscles, which were uncomfortable from the start. These cramps grow increasingly severe and become constant, agonizing.

While enclosed in a pack, the patient is required to pass his urine and feces into the pack—a diabolical ruling. I was always able to retain feces but I was forced to allow my bladder to empty after distention became painful. Once, when upset, my bladder sphincter seemed to go into spasm and, from the reclining position, I could not force it to open. Over a period of two or three hours, I suffered from increasing pain due to bladder distention. I begged and pleaded to be released so that I could empty my bladder, but I was

merely told by Mrs. Delaney to pass the urine into the pack. It was explained to me that most patients derived pleasure from urinating while in packs.

It is difficult to get out of a pack, but possible to do so, and I have wriggled out of many of them. During the struggle to get out of the pack, the sense of being overheated is most uncomfortable. Heat builds up rapidly, due partly to the heavy insulation of the body, and partly to the violent exertion of struggling. Thirst becomes at first extreme, and then almost unbearable. Sometimes a nurse will bring water if one yells loudly enough, but usually one waits for what seems like an interminable period before water is brought.

After struggling in a pack from two to ten hours, one grows weak from loss of fluid and salt, from constant pains, from the disgusting feeling of lying in one’s urine, from extreme thirst. The suffering is beyond the imagination of anyone who had not endured it. I feel sure that many times I found no sleep except in attacks of unconsciousness from which I would awaken probably in a few minutes. After these attacks of unconsciousness, I had the weird delusion of having slept for months or even years.

I can recall many occasions when I would suddenly break into a cold sweat and great drops of perspiration would pour out upon my forehead, nose and cheeks and run in rivers down across my face and neck. I believe that these phases of sudden, extreme, cold-perspiration and these attacks of unconsciousness represent dangerously severe stages of exhaustion.

After many hours, I was always so weak that I could

hardly raise myself from the bed. Sometimes an attendant placed his hand behind my head and raised me to a sitting position. When I then tried to stand, I usually found that my leg muscles were so cramped, and the rest of my muscles so weak, that I could not stand up. While being taken to the bathroom, I walked along stooped over, half crawling, with my knees bent and attendants holding me up. The next privilege was to sit on the toilet, sometime clean, and sometime smeared with urine and feces. As soon as I had finished at the toilet, and washed my face and hands, I was returned and placed immediately in a straightjacket without being allowed any period to recover from weakness, cramps, exhaustion and disgust. With the straightjacket came another type of suffering to succeed the one just endured.

For several successive days and nights this torture was continued. My body and mind fought on savagely and ceaselessly, but automatically. In spite of extreme sensations of exhaustion, I found no sleep, except in brief spells of what I believe was unconsciousness. I was never allowed any food except while under restraint. Usually Mrs. Delaney or Mr. Burns fed me—occasionally Tiny Hayes. Mr. Burns was more considerate in the feeding procedure than either Mrs. Delaney or Tiny Hayes. Tiny was usually brutal; Mrs. Delaney only a little less so. Breakfast was just a bowl of thin hot cereal without cream or sugar but with a little milk. A tablespoonful of this gruel mixture came at one’s mouth before the previous mouthful could be swallowed. If one did not open and swallow what was offered quickly enough the stuff would usually be emptied partly around the mouth,

and it would run in disgusting little rivers down the cheeks onto the neck, finding its way into pack or jacket.

Once, after Tiny had fed me two or three spoonfuls of breakfast cereal, my mouth was so full that I couldn’t accept any more and I turned my head to one side as the next spoonful came toward me.

“Don’t you want your breakfast?” Tiny asked in his usual booming, insulting voice.

“Oh don’t bother about feeding me!” I replied, even though I was hungry.

“That’s all we need to know,” said Tiny and left the room, taking my breakfast.

He did not return.

Once when Mrs. Delaney was feeding me my Sunday dinner, she fed me so fast that I could neither enjoy the food nor swallow it fast enough. I began to vomit.

Thus on many occasions, hunger was added to thirst and cramps, the pain of loneliness and incarceration, the agony of restraints, and the sudden details of torture which a staff of state hospital psychiatrists can devise.

AFTER some several days of this torment, Tiny Hayes, Mr. Burns, a powerful attendant, and a patient came in my room. They freed me from the bed and, leaving the straightjacket still on me, they took me—partly dragged me—to the bathroom. I felt particularly brittle, perhaps even filled with hatred. When I was brought back, the straightjacket was removed, and there was a pack already laid for me.

I backed into a corner.

“It seems to me that I’ve had enough of this sort of thing,” I said.

A wave of resentment swept over me. I clenched my fists and decided to fight rather than endure this agony any longer. Quickly, I turned toward the group and, with my blood boiling in anger and my eyes betraying the sudden change of temper, I advanced in a swift powerful movement of aggression. All four men turned pale and fell back. They showed surprise and real fear. Without striking a blow, the moral victory was mine.

I let my hands drop.

“All right, I’ll go through with another pack,” I said.

The four men came back cautiously as I lay down on the cold wet sheets. Two of them lined up on my left with Tiny Hayes at my right shoulder and Mr. Burns next to him near my feet. My head was raised off the bed. Suddenly I saw a long black rounded object coming down toward my head. My astonishment was so great that I made no attempt to duck away, though I was free to do so. I remained motionless as the instrument struck me on the right side of the forehead. The blow was painful. As the black object returned to Mr. Burns’ corner it looked as if it were bent in the middle. At first I thought it was a piece of lead pipe, but later I learned that Mr. Burns used a piece of heavy rubber hose on the patients and carried it in his pocket. The blow that he delivered to my forehead produced in its right upper portion an area of soreness with excoriation and swelling. A large vein in this area was damaged and went into a state of varicosity, protruding conspicuously. The soreness lasted for two to three weeks and the excoriation for almost a month. After

eight months, the vein has begun to return to its normal proportions. The staff psychiatrist, Dr. Boyd, examined the area but said nothing.

ON Sunday, two or three weeks after my admission to Westborough, at around 10 a.m. it was announced to me that visitors were on their way over. I lay there in my pack: cold, hungry, tired, weak. After a wait of ten minutes or so, I heard footsteps in the hallway and, through the gap in the partly opened door, I could see Gretta and our family physician, Dr. Porter, walking along together. They came into the room and greeted me. Gretta kissed me. We talked. Both Dr. Porter and Gretta kept on their winter coats. The room was frigid. The ground outside was covered with snow. A cold wind was blowing.

“Do you want a divorce?” Gretta asked.

This question struck me as a very serious one to put to a person supposedly ill. It came at a particularly difficult time. I thought for a few seconds.

“Yes,” I said.

Dr. Porter then immediately made some remark about how to obtain the divorce and the expediency of employing “cruel and abusive treatment” as a basis for the procedure. The conversation ran on about this and that.

I began to talk about the barbarities of the treatments I had been given.

“Well, Gretta, I guess we’d better go,” Dr. Porter said.

This remark gave me an even stronger feeling of having

to battle all alone, with no help to be expected from friends or relatives.

Dr. Porter asked whether I wanted him to leave the room so I could talk with Gretta alone. At first I asked him not to leave and then, in a little while, I requested that he leave us alone for a few minutes. Obligingly he left the room and stood outside talking with Mr. Burns.