Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (30 page)

Very few of Benny’s online followers had actually come to live in the village. “They don’t have to join physically. You can live a Samaritan life in the home. If they send a representative, I host them. People are always looking for something to stop them being bored. But it gives us pride that people find in us the people of truth.” As far as I could tell, Benny occupied a unique position in his community of just 750 people. But when I asked him who would publish the newspaper, attend conferences, and research Samaritan history when he was gone, he smiled and said: “We have a proverb: God makes a replacement in every generation. I think they will find a crazy like me in every generation.”

So far, one family Benny had corresponded with had come to live in al-Loz. They were American and had previously been Christian. One member of the family, Matthew, visited Benny while I was there, and I had the chance to talk to him. Matthew told me: “My mother was more and more interested in the Old Testament.” His mother, Sharon, wondered why Christians did not keep the Jewish law; wanting to observe it more closely, and searching on the Internet for information, she came across Benny’s name. “Six to eight years ago Benny visited, and we slowly started doing everything that the Samaritans do. The separation of unclean women, staying in our neighborhood for Shabbat, and so on. The old high priest invited Sharon to come and join the community, so she looked for religious studies programs and was accepted by Hebrew University.”

Eight years after the first encounter with the Samaritans, Matthew was in Benny’s house preparing for the Passover sacrifice. Other members of his family had not stayed the course: Matthew’s brothers had drifted away after growing tired of the need to attend regular prayers at the synagogue, and Sharon moved away to Jerusalem. Matthew, though, two years before my visit, had been invited to join the community’s observance of Passover and to eat the meat of the sacrificed lambs, which was the ultimate sign of acceptance. “Families live together, that’s what I love about the community,” he said. In practice, making his home among the Samaritans would mean learning both Hebrew and Arabic, which he had yet to do, but he planned to take on the task, and then study business and settle permanently in the community’s other neighborhood, in Tel Aviv, as the first American Samaritan. (The following year, I heard that he had abandoned this plan and gone back to America. No other outsider has since followed his lead by coming to live in the village.)

Benny gave me a tour of the village that afternoon, showing how the families were preparing for Passover. He simply wandered into people’s houses, I saw, without even needing to ring the bell or ask permission. In the basement storeroom of one house, where cribs and strollers had been stacked against the wall to make space, a man with the Arabic name Ghaith (his Hebrew name was Moshe) was spreading dough, made only with flour and water, over a hot curved metal plate called a

taboon

. A large stock was needed: as in Jewish tradition, only unleavened bread could be eaten during the seven days of Passover, which were about to start. Benny passed out to us a couple of pieces of the cooked bread, hot and crisp and flavorless. In the lead-up to and during Passover, the men were expected to handle cooking and other tasks. Ghaith’s wife sat nearby, in a slightly sour mood. “I do the cooking 364 days of the year,” she said in Arabic, “and nobody comes to take pictures of me doing it. And he does it one day a year and everyone thinks it’s amazing?”

There was one other Samaritan obligation that I had not yet seen, but I was given an intense introduction to it the next morning. Dozing fitfully in the guest hall where the Samaritans had put me up, I woke to an unearthly sound, a vigorous susurration echoing through the empty rooms around me. It was clearly no kind of conversation or argument, because there were around thirty voices speaking ceaselessly, but discordantly. For some minutes I could not work out where it was coming from. Then I realized: the guest hall was just next to the

kinsha,

the Samaritan synagogue. I went to see what was happening. At the entrance to the

kinsha

I had to take off my shoes and stow them in an outer room; just as Moses took off his shoes when receiving the Law on Mount Sinai (or Mount Gerizim, in Samaritan belief), so the Samaritans take off their shoes in the presence of that Law.

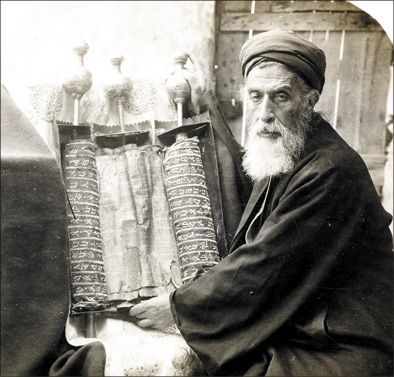

The Samaritans have preserved carefully over the generations their ancient scrolls, which record a Torah that differs somewhat from the Jewish one. Here in 1905 a Samaritan priest displays one such scroll for curious visitors. Stereograph in

Views of Palestine

[1905], Getty Research Institute

The prayer room faced east, and a niche at one end was sealed off with a yellow curtain, in front of which sat the white-robed high priest and his brother. There was a small clock and a menorah, the seven-branched candelabra, on the white-painted wall alongside; chandeliers and ceiling fans hung above. The building was constructed in the 1980s, but the niche housed vellum scrolls that date back centuries, possibly even millennia. Mills called them “the desire and the despair of European scholars,” and his determination to see them “grew almost into a fever.” When he eventually did, he found writing on one of them that claimed the document was written in biblical times. This was unlikely—not even vellum lasts that long—but perhaps it had been copied from a document from that period. There are seven-hundred-year-old scrolls in the British Library that were bought from the Samaritans in the nineteenth century. In places where the scrolls contain blessings that the priest touched as he recited them, the vellum is dark and worn.

The great murmuring that I had heard was produced by all of the village’s male Samaritans, dressed in thin cotton

jelaba

s that reached down to their feet, gathered in this room and reciting prayers, each in his own time and rhythm, using different words, not in unison. Every so often they would pause and prostrate themselves on hands and knees, touching their foreheads to the floor. Prayer time is when the Samaritans cover their heads, as some devout Jews do at all times with the

kippa

. The Samaritans had three different styles of headgear: a white prayer cap such as Muslims wear, a red

tarbush,

and a black beret. The last was favored by the Samaritans who lived in Tel Aviv, as they followed slightly more modern fashions. The effect was curiously transformative. A woolen jacket worn over the

jelaba

and a red

tarbush

made a man look as though he had stepped out of a book about the Ottoman empire; the man next to him, in a raincoat and beret, looked like a French artist.

For a week before Passover the Samaritans pray morning and night; on normal Saturdays, people pray either at home or at the synagogue. The prayers were extracts from the Samaritan Torah mixed in with religious poems written by Samaritans over the centuries. Most people seemed to know these by heart, but one teenager in spectacles was reading them from a book; at the back the younger children were less involved, and one fell asleep in the corner,

tarbush

falling to one side. His schoolmates, giggling, asked me to take his photo. This was as far as teenage rebellion went. Not turning up for prayer at all was apparently unthinkable. One of the teenagers, keen to chat in between prayers, told me a little about his family: he had a nephew who, as the firstborn son from a priestly family, would have the blood of the sacrifice smeared on his forehead that day, according to the tradition, and another nephew was studying computer science and wanted to serve in the Israeli army. The boy interrupted his life story occasionally to perform his prostrations with the others.

Later that morning, after the prayer service, I wandered along the main street. Toward the end of it was a shop selling beer and whisky, run by a Samaritan man called Jameel. We sat and drank coffee and talked for a while; some other men from the village joined us and looked at the photos I had taken. Why had I taken pictures of the sleeping boy? they asked suspiciously. Was I trying to make fun of them? Our conversation was interrupted several times by phone calls, from Palestinians in Nablus placing orders, after which Jameel would head off to fix some delivery or other.

“Yesterday was exhausting,” he said. “I was preparing unleavened bread for the family. It’s a big family!” His father had been a priest, and a huge picture of a Passover sacrifice ceremony had pride of place on one wall of the shop. I asked him how things were for the Samaritans. “I’m a bit worried,” he said. There was peace in Nablus for the time being, which was good, but it might not last. “Things should stay as they are. The intifada was bad for both sides, the Palestinians and the Israelis. Now it’s quiet, and safe. We need Nablus—we bring everything from there, all our food.” It was also where several Samaritans maintained shops and owned other property. The Samaritans had lived in Nablus until the late 1980s, when the first intifada frightened them into moving to their own separate village.

Yasser Arafat often boasted of the fact that the Samaritans were treated well under Palestinian rule, suggesting that it could be a precedent for Palestinian sovereignty over the West Bank, which would at the same time be open to Jews. He created a seat in the Palestinian parliament reserved for Samaritans. Jameel’s father had won the subsequent election, mostly on the back of Muslim votes: he was well known in Nablus, where his beer and whisky shop had apparently won him many friends.

Jameel’s father stood in a long tradition of Samaritans who advised Muslim rulers. Although the community in past centuries was collectively vulnerable and disadvantaged, individuals in it were often favored for sensitive posts because they stood outside the deadly tribal rivalries that split local Muslims. Those rivalries could put a Samaritan advisor in peril, though. A man called Jacob Esh Shalaby was an unusual Samaritan: he showed an early love of money and adventure, accepting money from a missionary to climb down Jacob’s Well and recover a Bible the visitor had dropped down it. Later he traveled to England (presumably breaking the Samaritan rules to do so) and wrote a memoir in 1855. In it he records the experiences of his great-uncle as treasurer for the governor of Nablus, as first one faction and then another seized power. This great-uncle was threatened with death, thrown into jail, and sentenced to execution—but fled, or was released, or was granted a reprieve. He managed to serve each of the rival warring families in turn. He survived, but his hair turned prematurely white.

Arafat’s welcoming of Samaritans into Nablus politics ended more benignly. Their reserved seat was abolished, leaving the larger Christian community as the only minority with reserved seats in the Palestinian parliament. As I sat with Jameel and a few other villagers joined us, I asked if the Samaritans felt slighted. No, they chorused; in fact, they were relieved. Involving the community in politics only caused trouble, and they would rather be neutral.

Neutrality can be hard to maintain, especially for a vulnerable minority community. So far, though, the Samaritans have hewed to their middle path with great skill. Later that day I wandered past the end of the village, through a gate that apparently had been put there to stop people from entering the village on the Sabbath. I walked by potato fields and thinly wooded slopes. On the same slopes in 1855, John Mills had heard jackals crying to each other at night and “vieing with each other in their antiphonal but hideous music.” At the time nobody lived on the mountain, and when they arrived to perform the Passover sacrifice, the Samaritans would pitch tents that they could stay in overnight. It seemed unlikely that any jackals survived there now. Houses were springing up everywhere, including one particularly lavish one that belonged to a Palestinian billionaire, Munib al-Masri. Some local workers were busy on one of the construction projects. They eyed me a little suspiciously until I spoke to them in Arabic, which delighted them. Things were peaceful, they said, which was good news. Were these houses still part of the Samaritan village? I asked. “No,” one of them answered, “the people living here are Palestinians.” Weren’t the Samaritans themselves Palestinians? “I suppose so,” he replied hesitantly, “especially the older ones; I’m not so sure about the younger generation. All right, then: let’s say these houses belong to Arabs.”

The man’s confusion was telling, because the Samaritans’ status is ambiguous. By the mid-twentieth century Samaritans and Muslims were coexisting better than they had a hundred years before. In the 1950s an envoy sent by Baron Edmond de Rothschild wrote to the baron that the Samaritans “enjoy good relations with Moslems.” Ahlam, a Muslim woman from Nablus, told me that she remembered going to Samaritan homes for the harvest festival of Sukkot in the early 1960s: “We went to their houses for festivals, and there was a particular one when they decorated their homes with fruit. They made a big effort to reach out, more than the Christians did, actually. They wouldn’t take hospitality from us”—because of the rules of

kashrut,

which state that Samaritans, like Jews, must only eat food prepared in a specific way—“but they would invite us to have food with them.” There were limits to this familiarity, as Ahlam discovered. She took private classes after school from one of the schoolteachers, who was secretly in love with a Muslim colleague. He dared to tell his pupil about it, but he could never tell the woman herself. Ahlam wondered why. She was too young at the time to understand the rigid codes that separated Samaritans from Muslims and other outsiders.