Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms (7 page)

Wilfrid Thesiger took this picture in 1950 of Arabs from the Iraqi Marshes using the

belem

, a type of boat dating back to Sumerian times, to move through the marshes, which were so isolated that he called them “a world in itself.” Photo courtesy Pitt Rivers Museum

Thesiger only briefly mentions the Mandaeans who lived alongside the Muslims in the marshes. He comments on their long beards, red-and-white checked head cloths, silver work, and habit of keeping ducks, which to local Muslims were unclean animals. Who knows: Thesiger might have met Nadia’s mother’s father, who worked for the leaders of the tribes fixing weapons for their hunting trips. “He could disassemble a gun and put it back together,” Nadia told me. Her father’s father made small, simple boats that the local people used for transport, as it was easier to move around the marshes on water than on land. These boats were called

belem,

a word with Sumerian roots.

One of the Mandaean festivals is called the White Days and commemorates the five days during which Mandaeans believe the world was created. During Nadia’s childhood this festival was in April (the Mandaean religious calendar contains no leap years, so its festivals move very slightly from one solar year to the next), and Nadia’s parents took her and her brother back to their hometown to celebrate with their extended family. Nadia described to me the town’s small houses, some the same shade of brown as the fields and the rivers, others made of reeds. The town’s Mandaeans all lived together in one district. The children played in the road and went from one house to another to ask for food or sweets. If they were lucky, they might be given the Mandaean specialty, wild mallard duck stuffed with cinnamon and cardamom, chopped onions, nuts, and sultanas, and boiled with dried limes and turmeric. To keep the children in line, the adults warned them that if they misbehaved, the wild horsemen of the desert would seize them and carry them off.

The White Days are a joyful festival, but the Mandaean New Year is a feast day with a more frightening side to it. Evil is said to walk the earth for thirty-six hours in the form of a female spirit called Ruha. In line with tradition, Nadia’s parents tried to make her stay indoors at this time, but without success. “I didn’t take it seriously,” she told me. “But I was told Ruha might take the form of a wasp, a bee, a tree, or a bird and would try to harm me. Or I might be hit by a car. It was an unlucky time to be outside.” Even in her secular household, this particular taboo still had some force.

A Mandaean man pictured by Wilfrid Thesiger in the Iraqi Marshes, applying pitch to a boat—just as Nadia’s grandfather once did. Photo courtesy Pitt Rivers Museum

In addition to a happy festival and a frightening one, the Mandaeans have a sad one, too. On the same day that Shi’a Muslims mark Ashura—the day of mourning for the death of the Prophet’s grandson Hussein and their own failure to come to his aid—the Mandaeans mourn as well, preparing a special meal of pearl barley soup, called

abul harith

. Sometimes they even join the Shi’a processions. They have various explanations for what exactly it is that they are remembering that day—“It’s in memory of a very stressful time,” was all that Nadia knew—but some Mandaeans believe that it commemorates the drowning of Pharaoh’s soldiers in the Red Sea. While Jews regard this incident as cause for celebration, the Mandaeans—for some reason that they themselves do not know—have come to empathize with the Egyptians. (Such days of mourning were once common across the Middle East. The Babylonians used to berate themselves once a year over their abandonment of the body of a pagan prophet, an act that they believed had caused the Great Flood.)

Nadia and her family also turned up with the rest of the community to give moral support to Mandaean men who were trying to enter the priesthood. The initiation ceremony is an arduous process. An aspirant must spend seven days in a reed hut without food or sleep. This is when he needs the support of the community: some of them stand outside the hut beating drums and chanting to make sure he stays awake, and women ululate. A

ganzibra,

the equivalent of a Mandaean bishop, stays with the aspirant and carves twenty-one words of power with his olivewood staff on the earthen floor of the hut: they are too secret to be said out loud, and when they have been learned the

ganzibra

sweeps over the dust to ensure that nobody else can read them. To complete the initiation the aspirant must eat a ritual meal, following an intricate and precise set of instructions. From then on, he must grow his beard long and keep strict rules of purity.

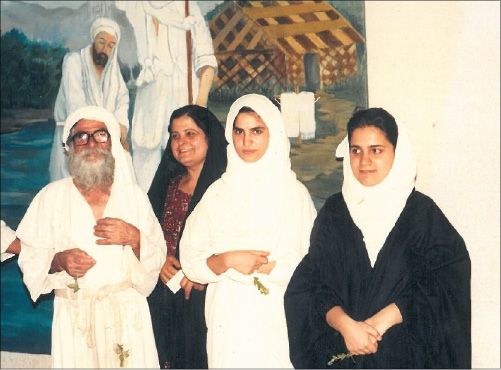

Nadia (far right) prepares for her baptism in Baghdad in 1991. She is veiled because of the holiness of the occasion, and carries a myrtle sprig. Behind the group, a picture shows a baptism being performed. Photo courtesy Nadia Gattan

But there is a higher level of holiness and knowledge, available only to those who, like Sheikh Sattar, had been appointed to the rank of

ganzibra.

This is an appointment that in the Mandaean tradition no living man can confer. A messenger must be sent into the afterlife to seek permission for it. The would-be

ganzibra

finds a person on the verge of death and stows a bottle of holy oil in the pocket of the garment adorned with gold and silver that dying Mandaeans are obliged to wear. “I have brought it to you,” the priest must say, “and you bear it to Abatur.” The ritual is complete after the messenger dies and his soul reaches Abatur, the judge of the dead, from whom he receives confirmation of the aspiring

ganzibra

’s request.

Only men can enter the Mandaean priesthood, and only men can marry non-Mandaeans and still pass on the religion to their children. A woman who marries out is debarred from baptism and cannot have her children baptized. Nadia thought that this inequality between the sexes was not the original spirit of Mandaeanism. For corroboration she looked back to the Mandaean scriptures: instead of Eve being made from Adam’s rib, as is told in the Book of Genesis, the Mandaean version says that both were made together. “I am sure there was a time,” she told me, “when Mandaean women could be priests, not just men.” She was right: in the Drasa da Yehia, a Jewish woman converts to Mandaeanism and becomes a priest. (Similarly, in ancient Babylon women could serve as priests. For that matter, women occasionally achieved secular positions of power in the ancient Middle East. The ancient Persian navy had a female admiral—Artemisia, back in the fifth century

BC

—and in the third century

AD

Palmyra had a powerful queen, Zenobia.)

—————

THE MOST IMPORTANT

Mandaean ceremony of all is baptism. One view of the Mandaeans has it that they adopted this practice from Jewish followers of John the Baptist fleeing eastward from Roman persecution; another has it that immersion in the waters of the river Tigris might have been an ancient practice in Iraq itself, as it was in Egypt. Certainly the traditions attached to the ceremony are distinctively Mandaean. As priests had done for the children of Iraq in pre-Christian times, a priest read the stars when Nadia was born and used them to devise a horoscope for her. And when she reached the age of seventeen, another priest in Baghdad used that horoscope to choose a secret name for her, called a

milwasha

. As she crouched in the waters of the Tigris, a girdle around her waist, a ring of myrtle leaves on her finger, and a white garment enveloping her head and body, he immersed her in the water three times, signed her forehead with water three times, made her swallow the river water three times, crowned her with myrtle, prayed over her, and named her. “It will be my name in religion,” she told me, “for as long as I live and beyond.”

Four aspects of that ceremony would have been familiar to any Babylonian of the first millennium

BC

. The first was the language in which it was performed. I got to see this language when I went to examine Mandaean holy books kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. Because of the books’ fragility, it took some persuasion before the staff would allow me to look through one of them. As I turned its pages I reflected that the Mandaean scribe who had copied it out with great care in the seventeenth century, spacing his lines out and crafting each calligraphic stroke, would have been horrified to see me reading it. Only Mandaean initiates into the priesthood were meant to be shown these texts.

The scribe would have been still more appalled by the volume’s leather cover, embossed with a fleur-de-lis, which the French royal librarian had put on the book when it entered the collection of King Louis XVI. Mandaean priests never used animal products such as leather to bind their books—a relic, some scholars say, of a time when their religion used to forbid meat altogether. They used calico as a binding material, or they engraved the pages on wood or even etched them onto lead with acid. The sharp-angled words that sloped from right to left across the page, black ink on the thick fibrous paper, were in a strange script: to my untutored eye it was similar to Arabic but with some extra letters and fewer of the dots that mark the Arabic alphabet. This was a specifically Mandaean dialect of Aramaic, the language of Iraq before Arabic.

Early Muslim writers, knowing that Aramaic had preceded their own language, Arabic, assumed that Aramaic was as old as the world itself and that Adam had spoken it after the Fall. In fact, when Babylon first emerged four thousand years ago, its official language was Sumerian, which was gradually displaced by a language called Akkadian—we can tell that for some time Akkadian was regarded as something like slang, because a four-thousand-year-old comic poem complains about what happened when the poet, as a boy, was caught speaking Akkadian at school (as well as breaking every other rule): “The door monitor said, ‘Why did you go out without my say-so?’ He beat me. The jug monitor, ‘Why did you take water without my say-so?’ He beat me. The Sumerian monitor, ‘You spoke in Akkadian!’ He beat me.” Only in the last centuries of Babylon’s existence did Aramaic become the city’s everyday language. A form of Aramaic is also spoken by Mandaeans in Iran, and a closely related language, with a distinct but similar script, is still in use among Christians in northern Iraq.

—————

NADIA’S RELIGIOUS NAME

was given to her after her priest’s careful study of the stars—the second Mandaean inheritance from the Babylonians, who were dedicated astronomers. It was the Babylonians who first divided the sky into the twelve signs of the zodiac, choosing twelve to match the number of cycles of the moon in every year. Such diligent watchers of the skies saw early on—certainly by 1500

BC

—that some stars behaved differently than others. They were brighter and moved through the sky in a different way. The observers called these

lu-bat

, meaning “wandering sheep.” The term was translated into Greek as

aster planetes,

meaning “wandering star,” which in turn gave us our word

planet

.

Babylonian astronomers identified five planets—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn (not Uranus and Neptune, which were invisible to the naked eye). They put the sun and moon in this group as well—making seven—and named each one after a god, such as Marduk, Ishtar, and Nebu. They then invented the week as a period of seven days, one for every planet god. (Rather neatly, seven days made up a quarter of a moon cycle, too.) We have inherited from the Babylonians the habit of naming the planets and the days of the week after gods: Mercury, Venus, Pluto; Saturday for Saturn, Thursday for Thor, Sunday and Monday for the sun and moon. For the Babylonians, one day in seven was an evil day, when activity should be avoided—which may have been the origin of the Sabbath day adopted by Judaism.

Because the planets were gods, their behavior was a sign of the gods’ intentions. The stars, too, were divine beings. Skilled astrologers called

umannu,

rather like Mandaean priests, advised the king on the omens they saw in the night sky and how to avert any ill they boded. They prayed to the stars (“O great ones, gods of the night . . . O Pleiades, Orion, and the Dragon”) before examining them. Eventually the Babylonians made predictions for people’s lives based on the disposition of the gods at their birth. For instance, a clay tablet survives that tells us of the birth of a boy called Aristokrates in 235

BC

: “That day: Moon in Leo, Sun in 12° 30’ of Gemini, Jupiter in 18° Sagittarius. The place of Jupiter means that his life will be regular, he will become rich, he will grow old, his days will be numerous.” The tradition has survived for millennia: in the back pages of European and American newspapers today are predictions that the old Babylonian astrologers might have recognized.