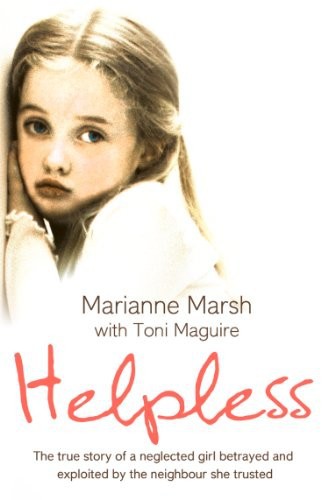

Helpless

Marianne Marsh

with Toni Maguire

The true story of a neglected girl betrayed and

exploited by the neighbour she trusted

T

he man had been looking for a little girl like me even before I was born.

A special little girl, he told me; one who needed love.

He widened his social circle to include young married couples, watched as they became parents and smiled with an inward sly delight when asked to be a godfather.

‘He’s so good with the young ones,’ his friends said.

He married when I was still the baby he had never met and considered his own small daughter for his needs. But his wife had grown to know his soul. She kept her children safe.

Unobserved, he watched me walking down country lanes as I went backwards and forwards to school. Saw my marks of neglect and knew then that I was the one; the one he had been waiting for.

He started frequenting the pub my father drank in and made himself known to him.

Listened to his tale of woe – low wages and small mouths to feed – and recommended him for a job that came with a decent-sized house.

It was no problem, he told my father; a pleasure to help.

People said he was such a fine man, his wife a lucky woman, and how fortunate my parents were to have met him.

He was everyone’s friend; the one who remembered wives’ birthdays and brought their children presents.

He was the trusted visitor, the favourite uncle.

He always kept sweets in the glove compartment of his car.

I was seven when I first met him, that man; the one who called me his little lady.

Years have passed since he and I last spoke. But still those memories are imprinted on my mind as clearly as though everything that happened happened just yesterday.

Title Page

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘T

ell us a story,’ my children used to say to me.

‘Where do you want me to begin?’ I would ask as I picked up a well-thumbed favourite book.

‘At the beginning, of course, Mum,’ and dutifully I would turn to page one.

‘Once upon a time …,’ I would start.

But when that story is my own and I have more years behind than in front of me the question is: where should I start?

The tale that I try to keep locked away in the recesses of my mind; that haunts my dreams – that started when I was seven.

My real story, though, started when I was conceived, or maybe even before, but it was not until I sat in my kitchen holding a piece of foolscap paper, with its small neat handwriting covering both sides, that I accepted the time had finally come to confront my past.

But where do I start? I asked myself.

At the beginning, Marianne, my inner voice replied. Your beginning, for you have to remember the years that came before to understand everything that happened.

So that is what I have done.

On every one of my birthdays, during the time I lived at home, before even a card had been opened or a present received, my mother told me how it had rained on the day I was born.

Not just showers, she always said, but great gushes of water that lashed the house and turned the country lanes into muddy paths.

The gutters, which my father never thought to empty of their dead leaves, overflowed. Rainwater streamed down the side of the house and then gushed noisily into already over-burdened drains. Over the years the outside walls had become stained a deep moss green and the blocked gutters had caused large patches of damp and mould to grow on the bedroom walls.

It was the early hours of the morning, before even the farmer’s cockerels had welcomed in the day, when I decided to enter the world. My mother had woken to stabbing pains and a damp nightdress and knew I was about to appear. Suddenly she was terrified.

She shook my father awake and he, grumbling at my inconsideration, hastily pulled on his clothes, tucked his trousers into thick boots, placed his bicycle clips over his ankles and rushed out of the house in search of the local midwife.

My mother heard the words ‘woman’s business’ and ‘no place for a man’ floating in the air behind him before the front door slammed and she was alone with only her pain and fear for company.

In what seemed like hours, but was in fact less than twenty minutes she always eventually admitted, the midwife was standing at the foot of her bed.

A sensible little square of a woman, she quickly took charge and tried to sooth my mother’s fears by informing her that she had delivered hundreds of babies. After a hasty examination she confirmed my imminent arrival.

‘Then do you know what she said?’ my mother would always ask at this point of the story. Obediently I would play the game and shake my head.

‘She just said that there was nothing she could do until my pains were closer together, and that,’ and my mother would draw breath to put emphasis on her next words, ‘all I had to do then was push! And then she asked where the clean towels she had asked to be left out for her were.’

My mother then continued to tell me about the remainder of that long, pain-filled day.

Tutting noises had come from the midwife’s mouth when she saw that my hungover father had forgotten to leave out all the items that she had requested, but with my mother’s help she eventually found everything she needed.

The next thing she accomplished was bullying a neighbour into agreeing to come next door and help when the time came, but until it did there was little to do. My mother listened to the buzz of conversation downstairs as numerous cups of tea were made and the two of them exchanged gossip. Over the day drinks were brought to her room and her face was wiped with a cool cloth, but mostly she was left alone.

‘Call me when you need me,’ were the words uttered by the midwife that failed to reassure, far less comfort, before she took herself downstairs to sit before the freshly lit fire.

I sometimes wondered how my mother remembered so much detail, but she assured me she did.

All that day she lay on her back, her legs raised, her knees apart and her hands moist with the perspiration of both agony and fear clutching hold of the twisted sheet. Her bed faced the window and, as she watched the water streaming across the glass, her body was wracked by more pain than she had thought anyone could endure.

Her throat ached with the screams that had been torn from it. She was drenched in sweat; it ran down her face, plastered her hair to her head and dripped from her chin.

More than anything, she wanted someone who loved her there; someone who would hold her hand, wipe her brow and tell her she was going to be all right. But there was only the midwife.

Evening came, and still it rained. She looked out through the window and saw glimmering in its panes her own face’s reflection, streaked with raindrops. It was as though, she thought, a million tears were running down her cheeks.

Eighteen hours after I had pierced my mother’s waters she gave that final push – the last one she thought her body was capable of – and I finally entered the world.

Luckily as I slid out of the warmth of my mother’s body I did not know how much my presence was resented. That took a few years to discover.

My father came home only once last orders had been called and heard the news that I was a girl.

I cannot think that he was very happy.

M

y earliest memory comes to me: a time when, too young to walk far, I was sitting in a pushchair. I felt again the motions of its movements and the sudden weight of shopping bags thrown in carelessly on top of me. How I longed for the expected warmth of my mother’s arms when she would stoop and lift me out. I heard the buzz of voices coming from the blurred faces above me, saw them peering down at me, but still I could not see myself.

Myself at three, small for my age, with straggly light-brown hair, a pale face that was often far from clean, and round blue eyes that already looked at the world with a cautious and slightly untrusting expression.

I did not know then that I was unloved, for without the joy of being cuddled or the comfort of being tucked up in bed and read to, or the security of being made to feel special, I had nothing to compare it to.

I had no word for fear either, so I could not have explained what I felt when goose bumps crept up my arms, the back of my neck prickled and my stomach felt as though a swarm of butterflies were fluttering around inside. But by the time I took my first shaky steps and formed my first words, I knew it was the sound of my father’s raised voice that caused these feelings.

The moment the front door opened and he staggered into the room he would yell at me, ‘Who do you think you’re staring at?’ At first, when I understood the anger but not the words, my mouth would open and release a loud howl that resulted in more shouts from him until my mother crossly removed me from his view. Later I learnt that the moment his presence filled the room I always had to make myself very small and very silent or, preferably, invisible.

The house where I spent my first seven years was a small cottage in a row of six. The front door led straight into our sitting room where narrow stairs led to the two bedrooms. My parents’ was just big enough for a double bed and a chest of drawers while mine, with its bare plaster walls and floors covered with brown cracked lino, was hardly bigger than a cupboard. The only furniture in it was a small bed covered with an assortment of old coats and torn bedding pushed against the wall opposite an uncurtained window.

The farm where my father worked as a labourer owned it and, like many farm workers’ cottages, our occupancy made up part of his wages.

The farmer, being old fashioned and cantankerous, refused to accept the rising cost of living and paid his discontented workers a pittance. ‘They have free housing, don’t they?’ was his defence. Unfortunately he also believed that ‘free housing’ came with no maintenance obligation for the landowner, and during the winter months it was a cold damp place. Neither rolled-up newspaper, placed along the bottom of doors, nor plastic sheeting pinned to rotten-framed windows stopped chilly drafts nipping tiny ears and noses and wrapping cold fingers around bare legs. Shivering, we sought a place by the fire where, with our fronts warm and our backs cold, we would huddle round its inadequate small black grate where damp logs burned.

When the sky darkened and rain sleeted down, making playing outside impossible, I spent my days in the tiny living room which served as kitchen, sitting area and, on the rare occasions when a tin bath made its appearance, bathroom. Furnished by cast-offs given by both sets of grandparents, I remember a dull maroon settee with sagging springs that nearly poked through the threadbare and faded material, a wooden dining table with four rickety and unmatching upright chairs and a scarred sideboard piled high with saucepans and other kitchen utensils. The living room lacked even one feature that could have made it either comfortable or welcoming – it was a dreary, dark room in a dreary, small house.

There were three doors in it: one to the staircase that led to the bedrooms, one to the back yard, where the washing of both clothes and dirty pans was done, and the third, the front door, led, it seemed for my mother, to nowhere. For apart from going to the shops for our food and basic supplies, she appeared to have little life outside of those walls.

Feeding us, which was never an easy task, seemed to take up almost all of my mother’s time. My father, even though his contribution to the housekeeping came second to his visits to the pub, expected a warm meal every evening. Regardless of the time he arrived home, should it not be on the table within minutes, his bellows of rage rent the air and meaty fists rose in fury.

He was a binge drinker, as we have now learnt to call them. My mother never knew whether he would go straight to the pub after work or come home first for supper and then head to the pub to drink until his pockets were empty.

Knowing that on the last days before payday he would look for any remaining housekeeping money, my mother tried to hide small amounts so that she could always ensure that there was at least bread and milk in the house. Within hours of her finding a new hiding place for the few coins she had secreted away, my father’s desire to drink seemed to give him an uncanny power of detection and he always discovered it.

On those days the tension in the room was almost a palpable force. He’d slurp his tea, shovel his food into his mouth while his eyes darted around the room and my mother, knowing what was to follow, hovered nervously nearby. Maybe she prayed that just this time his mood would lighten and he would choose to stay in.

But he seldom did.

Sometimes he would ask for the money with a smile, other times with a grimace and sometimes with threats but, however he presented it, my mother knew it was a demand and not a request.

Her protestations that there was nothing left were always received with an angry glare.

‘Sodding liar, that’s what you are,’ was his normal response. ‘Now give it to me if you know what’s good for you.’

My little body would shake with fear and I would slither quietly from my chair and creep behind the settee. With hands held over my ears and eyes screwed up tightly, I tried to block out the images and sounds of what was happening. I would hear the scrape of his chair being pushed violently back, the sound of his feet in their heavy working boots stamping across the room, the crash of saucepans thrown to the floor and the clatter of sideboard drawers being emptied onto the floor.

Those sounds mixed with my father’s angry shouts of ‘Where are you hiding it, you bitch?’ and my mother’s wasted protests of ‘There’s nothing left’, until the kitchen rang with the sounds of his search and her pleas.

The roars of rage would increase and were followed by the unmistakable thuds of fists connecting with a body. My mother’s sobs, the thunder of heavy feet on the wooden stairs and then finally his triumphant shout would let me know that his search had finally yielded its booty.

‘There, you useless slag, I said you were hiding it from me.’

Once again the lure of the pub had won. It called out to my father, its siren’s call erasing all thoughts of his family’s needs.

When the door slammed, announcing his departure, I would remove my hands from my ears, open my eyes, uncurl myself and hesitantly come out from behind the settee. Each time it happened I felt a lump in my throat when I saw my mother sitting slumped in utter despair.

The red marks of a handprint were on her face, a trickle of blood smeared round the edge of her already swelling mouth, a bruise was beginning to stain her arm and the tears of despair were sliding silently down her face as she surveyed the chaos around her. It would make me want to run to her and offer her comfort. There were times when, without the energy left to push me away, she let me nestle against her knee, but mostly, as soon as I said the word ‘Mum’, she gave me a look of such frustrated anger that I shrank back from her.

‘Mum what, Marianne? Can you not leave me alone for one moment? Now what do you want?’

At that age I did not have the words to tell her that I wanted to feel safe, that I wanted to crawl onto her lap and have her arms around me and be told that everything was going to be all right.

Instead, faced with her rejection, fat tears would spurt from my eyes as I wailed with my answering misery.

Anger usually left her face then, to be replaced sometimes by a mixed expression of fleeting guilt and resigned impatience.

‘Oh, stop your whingeing now! It’s not you he went for, is it? Let’s find something to dry your tears.’ She would fumble in her pocket for the grubby rag that passed for a hanky and hastily dry my tears. ‘You know it’s not your fault, Marianne.’

Those brief moments of rough maternal kindness would temporarily console me but I still believed that somehow it must have been my fault that she was angry. After all, there was no one else there to blame.

When there was not enough money left for even the most basic of groceries, my mother had to rely on the good nature of others to give her credit or, worse still, when things were really bad, handouts.

I hated those times when, standing next to her, I heard her stumbling excuses and knew that not only the shopkeeper but the other customers in the queue behind her did not believe her story. I felt a wave of shame as I saw their looks of pity mixed with contempt and wondered if their whispered comments were about us. I watched the blush of embarrassment and shame spreading across my mother’s cheeks as she realized she had not been believed.

The cheapest cuts of meat were bought from the butcher. The scrag end of a piece of lamb could last for a week when a bone thick with marrow was added for additional body and flavour. Generous portions of potatoes plus an assortment of whichever vegetables were in season turned it into a nourishing stew that was served night after night.

There was another period, worse than the others, when my father was hardly home. When he finally did appear his face was unshaven, his eyes bloodshot. The smell of the pub, that mixture of alcohol, cigarettes and stale sweat, clung to him, and his pay packet was empty.

It was on these occasions that my mother had to beg the butcher for the meaty bones normally set aside for the well-off customers to give to their dogs. He looked pityingly at her haggard face and at my own pale one. ‘Think you deserve these more than pampered Fido and Rover,’ he said, also slipping some fatty lumps of meat trimmings cut from his dearer joints into the paper parcel. ‘No charge, luv,’ he would say and shrug aside her grateful words of thanks. Each time his niceness used to somehow embarrass my mother more than his usual brusqueness would have done.

At these times my mother’s stews became even thicker with potatoes and cabbage leaves, but thin with meat. Shepherd’s pie became mash and gravy, and greasy white dripping replaced butter and jam on our bread.

‘Have to leave the meat for your father,’ she would say to me each time she gave me cabbage and chunks of pale potatoes swimming in the grease-topped gravy.

I would just look at my father’s empty chair and the place that was laid for him at the table and wonder if he would come home after I was in bed.