Henry IV (52 page)

Authors: Chris Given-Wilson

33

R. Griffiths, ‘Prince Henry, Wales and the Royal Exchequer’,

Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies

32 (1985), 202–15.

34

Original Letters

, i.37;

Foedera

, viii.390. This was on Wednesday 11 March; the prince said he would have sent the chieftain to the king except that the captive ‘still could not ride easily’.

35

CPR 1405–8

, 6 (indentures for 1,000 men-at-arms and 5,500 archers, including 864 members of the king's retinue, for service in Wales, March 1405).

36

This was the battle of Pwll Melyn (

Usk

, 212–13; Davies,

Revolt

, 231;

SAC II

, 435).

37

Ancient Irish Histories: The Works of Spencer, Campion, Hanmer and Marleburrough

, ed. J. Ware (2 vols, Dublin, 1809), 19. They also carried off the shrine of St Cybi from Llangiby to Dublin.

38

RHL II

, 76–9.

39

Saint-Denys

, iii.322–9;

Monstrelet

, i.81–4;

SAC II

, 463–5; Davies,

Revolt

, 193–6. For Hangest in 1400, see above, pp. 171–3.

40

SAC II

, 465.

41

For Owain's letters to Charles VI, dated at Pennal on 31 March 1406, see T. Matthews,

Welsh Records in Paris

(Carmarthen, 1910), 40–54, 83–99; Davies,

Revolt

, 169–72.

42

Wilson, ‘Anglo-French Relations’, 280;

SAC II

, 407;

Saint-Denys

, iii.181, 197, 228; E. Carus-Wilson and O. Coleman,

England's Export Trade 1275–1547

(Oxford, 1963), 122, 138. January 1405 saw the first direct Anglo-Burgundian talks for a mercantile truce.

43

Saint-Denys

, iii.258–63, 317–21;

SAC II

, 437–9, 460–1;

Foedera

, viii.397.

44

D. Grummitt, ‘The Financial Administration of Calais during the Reign of Henry IV, 1399–1413’,

EHR

113 (1998), 277–99, at p. 285. For rumours of treason at Calais, see

SAC II

, 388–9;

RHL

, i.xc–xcii, 284–93. In May 1403, the victualler of Calais, Reynald Curteys, was imprisoned for debt by the king's council (C 49/48, no. 4).

45

Phillpotts, ‘Fate of the Truce’, 69–72.

Chapter 17

AN EMPIRE IN CRISIS: IRELAND AND GUYENNE (1399–1405)

Challenges to Henry IV's rule during the early years of his reign came from every part of the king's dominions, including the lordship of Ireland and the duchy of Guyenne. Both of these had been claimed by the English crown since the mid-twelfth century, but they were very different. Guyenne, inherited rather than conquered, had barely been settled by English landholders, and its native Gascon lords and townsmen were described as ‘the king's loyal subjects’; they in turn expressed a consistent desire to maintain their attachment to the English crown, partly for commercial reasons and partly for fear of domination from Paris. The native or Gaelic inhabitants of Ireland, in contrast, were ‘the king's enemies’ or ‘the wild Irish’, an inferior and semi-barbaric people who stubbornly refused to accept the reality of conquest and settlement by English landholders.

1

To make matters worse, their obduracy seemed to be paying off. During the thirteenth century, English rule in Ireland had expanded to include half or more of the surface area of the island, but since then a slowdown in the rate of emigration from England, a succession of political checks and lengthy minorities among Anglo-Irish landholders, and a vigorous Gaelic counter-offensive had eroded the settlers' position. Dazzled by visions of continental glory, neither the king nor the great English lords who held estates there prioritized Ireland; absenteeism became endemic and the task of upholding English rule was increasingly left to men of lesser rank.

2

Meanwhile, those Anglo-Irish families which had made Ireland their home and had few remaining interests in England, such as the Geraldine earls of Desmond and Kildare and the Butler earls of Ormond, became increasingly acculturated to the local way of life, a tendency condemned as degenerate in the 1366 Statute of Kilkenny, which forbade intermarriage between native Irish and English settlers and prohibited the latter from using the

Irish language, dress or pastimes. At the same time, intercourse between Westminster and the ‘English of Ireland’ grew more peevish, with much talk in the Irish parliament of the ‘liberties of Ireland’ and many unofficial treaties made with Gaelic lords.

3

‘Liberties’ certainly did not mean separatism, however: the Anglo-Irish needed the king of England as much as he needed them, and the earls of Ormond in particular were adept at securing privileges from the English monarchy, especially when they feuded with the Geraldines, as they often did.

4

Power struggles in England exacerbated these problems.

5

Richard II's 1394–5 campaign, the first by an English king in Ireland for nearly 200 years, was notable for its attempt to bring the native Irish lords into a more direct relationship with the crown and thus to establish a more inclusive framework for relationships between the competing polities on the island (although it naturally also aimed to reassert English control), but its achievements were largely undone by what followed.

6

When Richard left Ireland in April 1395, he appointed Roger Mortimer, the twenty-one-year-old earl of March and Ulster, as his lieutenant there, but on 27 July 1398 Roger, having fallen under suspicion in England, was abruptly replaced by one of the rising stars of Richard's court, Thomas Holand, duke of Surrey. In fact, unbeknown to the king, Roger had been killed just one week before this, in a skirmish with the O'Byrnes at Kellistown (County Carlow).

7

Yet another Mortimer minority (no earl of March since 1330 had lived beyond the age of 31) necessitated a second royal campaign, but the foreshortened fiasco that was Richard's 1399 expedition was the starkest reminder yet that policy towards Ireland was at times but a reed in the crosswinds of English factional rivalries.

Given that Roger's son and heir Edmund was not only earl of Ulster, lord of Connacht, Trim and Leix and the holder of half of Meath, but also had a plausible claim to Henry's throne, it would be surprising if his

exclusion from the succession in 1399 was not greeted with some disquiet in Ireland. However, it was probably caution, or perhaps merely a breakdown in communications, which was responsible for the fact that two-and-a-half months on from Henry's coronation the chancellor and treasurer in Dublin were discovered still to be issuing writs in the former king's name and were crisply ordered to substitute HENRY for RICHARD.

8

Yet Henry could hardly be faulted for not appointing the eight-year-old Edmund as his lieutenant. Perhaps more indicative of his intentions was the fact that the man he did appoint, Sir John Stanley, although well versed in Irish affairs, was only given £5,333 a year, more than half of which was to be raised from revenues within Ireland, which were always at the mercy of events. Royal lieutenants between 1361 and 1399 had usually been given between £6,000 and £8,000 a year and sometimes more.

9

The reissue in December 1399 of the 1380 statute ordering absentee English landlords to return to Ireland or forfeit two-thirds of their profits was a further attempt to make the colony self-financing, but was largely unworkable because of the number of exemptions granted.

10

Henry, it seemed, was intent on governing Ireland on the cheap, but, as his financial embarrassments mounted, even the relatively small amounts that the lieutenant was meant to receive from the English exchequer proved hard to secure.

11

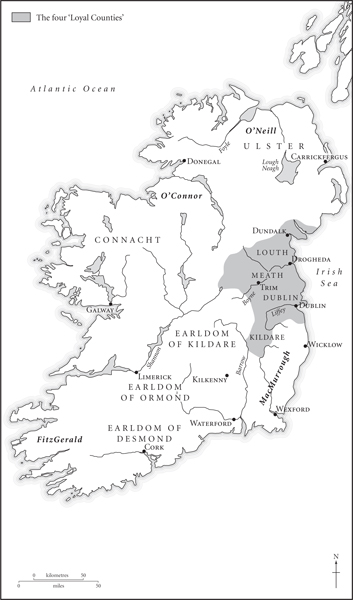

Aside from the retinue of 100 men-at-arms and 300 archers stipulated in Stanley's indenture, the defence of the ‘four loyal counties’ (Dublin, Kildare, Meath and Louth) was entrusted to Sir Edward Perers, who had been appointed as marshal of the armed militia of Ireland by Richard II, but proved a stalwart upholder of Lancastrian rule there. James Butler, earl of Ormond, who since the death by drowning of his rival, the earl of

Desmond, in 1399 had emerged as the leader of the Anglo-Irish nobility, also showed himself more than willing to cooperate with the new regime.

12

Yet the lieutenant's resources were woefully inadequate to his task. Despite attempts to pacify Art MacMurrough, the ‘chief captain of his nation and of all the Irish in Leinster’, he openly defied English authority in County Carlow and the northern part of the liberty of Wexford. In Ulster, meanwhile – where the discontinuity of Mortimer leadership had for years allowed the O'Neills of Tyrone to raise black-rent (protection money) almost at will, intermittently enforcing their demands with devastating raids – matters were further complicated during the summer of 1400 by the arrival of a Scottish fleet at Strangford Lough (County Down), which routed an English force led by the constable of Dublin castle.

13

Stanley was eventually recalled by the king on 18 May 1401, less than halfway through his agreed three-year term, and was followed back to England by Thomas Cranley, archbishop of Dublin and former chancellor, who, in an interview with the king on 30 June, gave Henry a chilling account of the decay of English lordship in Ireland.

14

Map 6

Ireland in Henry IV's reign

The king responded decisively, committing the lieutenancy to his second son Thomas – an attempt (despite the fact that Thomas was only thirteen years old) to demonstrate a more serious commitment to the colony by giving it a figurehead to act as a focus of loyalty for the Anglo-Irish, and perhaps for the Gaelic lords as well. As an earnest of his intentions, the king also promised Thomas £8,000 a year, all of which was to be drawn from the English exchequer.

15

This striking change of direction was an acknowledgement not simply of the fact that his hope of making the English colony in Ireland largely self-supporting had failed, but also of the danger that the rapidly escalating Welsh rebellion might light a similar fire across the Irish Sea. Owain Glyn Dŵr had the same thought, and wrote to the Scottish king and the Irish lords in November 1401 to invite them to support his struggle against ‘our mortal enemies, the Saxons’, appealing to the kinship which bound the Celtic peoples and the fact that their eventual triumph had been foretold by Merlin, and adding pointedly that the longer the Welsh revolt continued, the longer would be the respite enjoyed by the

Irish from the unwelcome attentions of the English. Calls for common action between England's Celtic neighbours had been issued before, and the threat of Ireland providing a base for Welsh rebels, to say nothing of the threat to the English colony there, became graver still with the defection of Edmund Mortimer in the summer of 1402.

16

Edmund had acted as governor of Ireland in 1397–8, and if the foremost adult representative of the greatest English family in Ireland had decided to throw in his lot with the king's enemies, who was to say which way its clients and well-wishers would turn?

Prince Thomas thus stood in need of wise heads about him, and he was not disappointed. Archbishop Cranley, a man much praised by contemporaries, was reappointed as chancellor, and the Lancashire knight Sir Laurence Merbury as treasurer; both remained in office until 1406.

17

Edward Perers stayed on as marshal, but overall responsibility for defence (under the prince's authority) was given to Sir Stephen Le Scrope, who was appointed deputy lieutenant and ‘governor of the wars’. The Navarrese esquire Janico Dartasso, who like Le Scrope had distinguished himself in Ireland under Richard II, also returned with Prince Thomas and would spend much of the reign there, serving as justiciar, mediator, army commander and admiral.

18

Thomas and his deputies also established a good working relationship with the earl of Ormond, who in turn looked to the prince not to obstruct his attempts to expand his influence in Munster at the expense of the Geraldines.

19

Ormond was not disappointed, for the prince needed whatever help he could muster. Before his arrival in Dublin in November 1401, a number of

Gaelic lords had promised allegiance to his father's crown, and a brief foray in January 1402 secured the submission of others, but the protection of English enclaves was a Sisyphean task and often enough the best that could be offered to beleaguered towns was permission to make truces and trade with their Irish neighbours.

20

In July 1402 the mayor of Dublin, John Drake, led a force of Dubliners to Bray (in the medieval county of Dublin) where they slew 493 Irish rebels, ‘all men of war’,

21

but by February 1403 Janico Dartasso was reporting that he dared not proceed from Leinster into Ulster because the roads were too dangerous.

22

The problem was not just the native Irish but also members of the Anglo-Irish gentry, one group of whom abducted the chief baron of the Irish exchequer, Richard Rede, while another murdered John Dowdall, the sheriff of Louth, in September 1402.

23

This was the prelude to the revolt that broke out in Ulster in May 1403, which was supported not just by Scottish galloglass but also by Anglo-Irish knights and esquires. Carrickfergus was ‘totally burned’ and Sir Walter Bitterley, the royally appointed steward of Ulster during the earl of March's minority, killed. Initially the English government reacted with fury, but within a few years the perpetrators had been pardoned. Although this revolt preceded and was thus not a consequence of the Percy rebellion in England, it may well have been fomented by disgruntled supporters of the Mortimers, and was exactly the type of ripple effect the king must have feared following his usurpation and Edmund Mortimer's defection the previous year.

24