Henry V as Warlord (34 page)

Read Henry V as Warlord Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

Baugé was avenged. Moreover a whole string of dauphinist fortresses surrendered in consequence, including Crépy-en-Valois and Offremont – the castle of the Guy de Nesle who had fallen into the moat at Meaux. Henry rode through the countryside receiving the surrender of each stronghold in person, mopping up any local resistance.

Then he celebrated by going to Paris to meet his queen. Monstrelet says that he and his brothers greeted Catherine ‘as though she had been an angel from heaven’. The son and heir who was the cause of so much congratulation had been left behind in England. The reunion took place at the great castle of Bois-de-Vincennes just outside Paris.

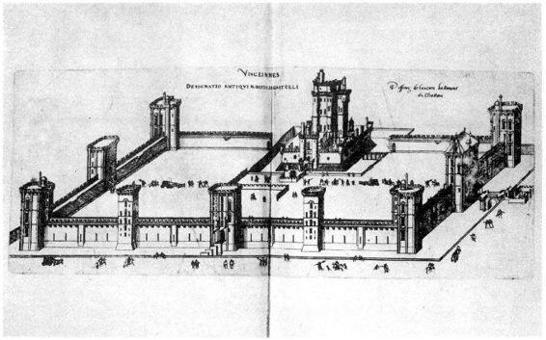

Today Vincennes may seem gloomy, a soulless barrack of a place. It has unhappy memories; the Due d’Enghien was shot in the moat in 1804 as was Mata Hari in 1917, it was General Gamelin’s headquarters in June 1940 after which foreign troops occupied it again for four years. Yet Henry’s fondness for Vincennes is understandable. Originally a hunting lodge, being in the woods it was ideally situated for the king’s favourite relaxation – if ever he had time. Catherine’s grandfather, the great King Charles V, had completed the

donjon

during the 1370s and it was here that Henry lived; his bedroom may still be seen. There were three mighty gatehouses and six tall towers, all linked by curtain walls, and providing enviable accommodation for his high ranking-officers. A hunting scene in the

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry

shows the fortress-palace in the background, much as it must have looked at this time, and one can see why the Monk of St Denis calls it ‘the most delectable of all the castles of the king of France’.

21

Moreover Vincennes was only three miles from Paris – close enough to overawe the capital if need be, and sufficiently far away to avoid any danger from the mob or dauphinist plots.

Vincennes in 1576, still just as it had been in Henry V’s time. The

donjon

(or keep) within the inner moat is where the king died in 1422.

At the Louvre, says

The First English Life

, echoing Monstrelet’s chronicle, ‘on the proper day of Pentecost the King of England and his queen sat together at their table in the open hall at dinner, marvellously glorious, and pompously crowned with rich and precious diadems; dukes also, prelates of the church and other great estates of England and of France, were sat every man in his degree in the same hall where the king and queen kept their estate. The feast was marvellously rich and abundant in sumptuous delicate meats and drinks.’

22

Unfortunately the splendid effect was somewhat tarnished by no food or drink being offered to the crowds of spectators, as had always been the custom in former days under the Valois monarchs.

The

Brut of England

records with relish, ‘But as for the King of France he held none other estate nor rule but was almost left alone.’

23

Charles VI stayed forlornly at the Hôtel de St-Pol, deserted by his nobles since, so Monstrelet informs us, ‘he was managed as the King of England pleased … which caused much sorrow in the hearts of all loyal Frenchmen.’ Chastellain comments indignantly that Henry, this ‘tyrant king’, despite promising to honour his father-in-law of France as long as he lived, had made ‘a figurehead [

unydole

] of him, a cipher who could do nothing’. Chastellain too says that the spectacle brought tears into the eyes of the Parisians.

24

Henry spent two days in early June at the Hôtel de Nesle, where he watched a cycle of mystery plays about the martyrdom of his patron, St George. These were staged by Parisians who hoped to ingratiate themselves with the heir and regent of France, their future sovereign. Shortly afterwards he and Catherine, taking with them King Charles and Queen Isabeau, left the capital for Senlis.

A week later a Parisian armourer, who had once been an armourer to Charles VI, together with his wife and their neighbour, a baker, were caught plotting to let the dauphinists into Paris. A strong force of the enemy were standing by in readiness near Compiègne. The civil authority beheaded the armourer and the baker, and drowned the woman.

25

‘

ung royaulme dyabolique

’

Jean Juvénal des Ursins

‘“The three Frances”. In its simple way that formula marks one of the most sombre moments in the nation’s history.’

Jean Favier,

La Guerre de Cent Ans

T

here were now three Frances – ruled respectively by the heir and regent, the Duke of Burgundy, and the dauphin. As Chastellain puts it, Henry V ‘came into France at a time of divison, and amidst this division estranged still further by his sword those who were divided’.

In 1422 Henry’s position in France appeared most impressive. ‘All the country across the Loire is black and obscure, for they have put themselves into the hands of the English,’ laments Jean Juvénal. Invincible in the field, a commander to whom no fortress was impregnable, the king controlled a third of the country and the capital. It genuinely seemed that one day he might be crowned and anointed at Reims with the oil of clovis as king of France. Some modern English historians give an impression that France was too divided by regional loyalties, so much without a sense of nationalism that the inhabitants of Lancastrian France accepted the regime, that a Franco-English monarchy might have survived. Certainly many Frenchmen ‘collaborated’ but to claim, like one distinguished twentieth-century English historian, that the Rouennais ‘settled down without a murmur under the sway of a descendant of their ancient dukes’, is a distortion.

1

Henry’s so-called policy of conciliation was accompanied by what Edouard Perroy terms ‘a regime of terror’.

2

When Perroy wrote this he himself was on the run from the Gestapo.

Discussing ‘Lancastrian France’ one has to distinguish between the duchy of Normandy (with the neighbouring territory conquered before the Treaty of Troyes) and the small area including Paris which was technically Henry’s ‘kingdom of France’. The duchy was very much an occupied country whereas the kingdom was more like a puppet state. In the latter all officials save the military were Frenchmen. Most of them were Burgundians and the appointment of many must have been due to Duke Philip’s influence, though not invariably – there were occasional grumbles at the removal of Burgundian nominees. The English population of ‘occupied’ Paris was seldom more than 300; at one moment (after Henry’s death) the garrison in the Bastille consisted of eight men-at-arms and seventeen archers. The official in charge of Parisian police was a Frenchman, and so was the president of the

parlement

. So few English can scarcely have been much in evidence in a city whose population remained at well over 100,000 despite famine and a mass exodus. Jean Favier says that one was most likely to see them in the taverns, and they were good customers of the Glatigny prostitutes or at the Tiron brothel.

3

However, the Parisians’ comparative freedom from English rule must not be seen out of context. The ‘lands of the conquest’ were a mere dozen miles away, while Paris was ringed by fortresses with English garrisons, the nearest being at Bois-de-Vincennes only three miles off. The one at Pontoise numbered 240 men and reinforcements could be rushed up river into the capital at a moment’s notice. On occasion the force at the Bastille could show that it was perfectly adequate for cowing the Parisians, its archers running through the streets and shooting at them and at their windows indiscriminately. Moreover it was backed up by a large

milice

recruited from the citizens; crossbowmen and spearmen who could at least be trusted to fight against the dauphinists of whom they were even more frightened than of the English. The former Armagnacs, who called such militiamen ‘

faux français’

, had some nasty massacres to avenge and their raids on the city’s suburbs rivalled those of the English in ferocity. This relative freedom and the dauphinist threat did not mean that the Parisians were any the more inclined to like Henry’s troops. That staunch Burgundian, the Bourgeois of Paris, pitied the king’s prisoners, and the city’s prisons were filled to overflowing by his prisoners more than once.

Even an English chronicler, Walsingham, has to admit that Henry was most unpopular in Paris, that force was sometimes needed to control its people.

4

Some of its clergy were openly dauphinist. In December 1420 the chapter of Nôtre Dame elected Jean Courtecuisse Bishop of Paris – a man of exemplary life who was an avowed dauphinist – despite Henry’s attempts to bully the canons into choosing a Burgundian nominee. At one moment Exeter, the military governor, put two of them under house arrest. The chapter also refused to contribute to the cost of a detachment of militia which the city had to send to the siege of Meaux. Visiting Nôtre Dame Henry gave the derisory (for a king) offering of two nobles – a noble was worth a third of a pound. Eventually he persuaded the pope to appoint Courtecuisse to another see.

There is more than enough evidence to show that in both the kingdom and the duchy the French population bitterly resented the English presence; the way in which invaders from across the Channel had taken advantage of their civil war to conquer and dominate them. Agincourt was a truly national catastrophe, shared by Burgundians and Armagnacs alike, its memory remaining firmly in their minds. The latter blamed the English for their sufferings even more than they did the Burgundians. ‘This storm of misery unleashed on us by the people of England,’ (‘

le gent d’Angleterre

’) says the chronicler Jean Chartier.

5

Bishop Basin gives a horrific picture of the sort of lives which English settlers must have lived in Lancastrian France. Although he is writing specifically about a truce in Maine and Anjou during the 1440s, such conditions must have been the norm everywhere, from the very beginning. His is the evidence of an eyewitness who had lived under the English occupation until he was nearly forty:

Shut up for years without almost any respite behind the walls of towns, castles or fortresses, living in fear and danger as though condemned to life imprisonment, they were marvellously happy at the thought of emerging from their long and frightening incarceration. It was sweet to them to have escaped all the perils and alarms among which they had lived since childhood till the days of white hair or extreme old age.

6

Moreover we know that in Normandy, for example, the population had fallen by a half after eight years of English occupation, partly because of famine but principally because of emigration by all classes – whether dispossessed seigneurs, ruined bourgeois, starving peasants or despairing beggars. Admittedly the misery from which they fled was partly due to dauphinist raiders and brigands but neither would have come but for Henry’s invasion.

Most of the Normans, Picards and Champenois who emigrated did so because of social and economic distress.

7

The presence of more than sixty garrisons in the countryside meant ruin for many farmers in the conquered territories. Since these were irregularly paid and there was no real commissariat despite Henry’s efforts, the troops had little choice but to continue living off the country, requisitioning food, drink, fodder and anything else they wanted from the locals; even the irreplaceable oxen which drew the ploughs might be slaughtered, while horses and farm carts must have been taken on a very large scale. No doubt the big Percheron horses made excellent remounts for men-at-arms. The peasants were further demoralized by having to pay protection money and tolls, by the harassment of their womenfolk and by all the evils which accompany armies of occupation. In Normandy, where the English were most numerous (and which had suffered a series of bad harvests before their arrival), agriculture all but collapsed. As has been seen, the king was unable to control his troops.

Worse still, many soldiers regarded the country people – which meant the overwhelming majority of Frenchmen and Frenchwomen – as their natural prey. Again, Basin writes of what he had witnessed himself:

The troops on both sides, constantly raiding each other’s territory, dragged the peasants away to their castles and fortresses where they incarcerated them in noisome prisons or at the bottom of deep pits, torturing them in every conceivable way, trying to force them to pay the heavy ransoms which they demanded of them. In the cellars and vaults beneath every castle or tower one would always find poor peasants snatched from their fields, a hundred or two hundred, sometimes even more, depending on the number of kidnappers. Often many, incapable of paying the sums demanded, found no mercy from the raiders and died from hunger, weakness or vermin.

8