Henry V: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History Paperback (12 page)

Authors: Marcus Cowper

Tags: #Military History - Medieval

15th-century illustration

flight away from the enemy. Because of the example they set many of the

of the battle of Agincourt,

French left the field in flight.

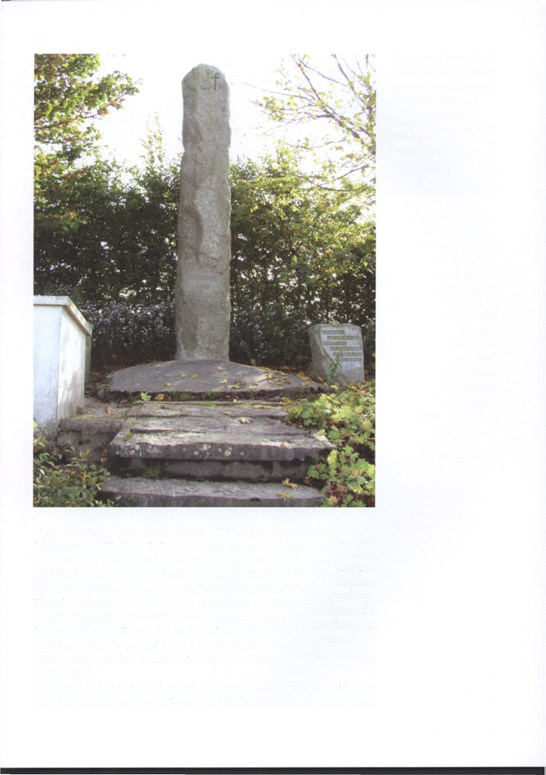

showing the castle in the

Soon afterwards the English fell upon them body on body. Dropping their

background, from the

bows and arrows to the ground, they took up their swords, axes, hammers,

Abrege de to Chronique

falchions and other weapons of war. With great blows they killed the French

d'Enguerrand de Monstretet

who fell dead to the ground. In doing this they came so far forward that they

(Ms.frangais 2680,

almost reached the main battle, which was following in behind the vanguard.

fol.208r) held in the

After the English archers the King of England followed up by marching in with

Bibliotheque Nationale,

all his men-at-arms in great strength.

Paris. Enguerran

Monstrelet was a

The intervention of the lightly armoured and manoeuvrable English archers Burgundian chronicler

appears to have been crucial in what was a hard-fought battle. Sources on active at the court

both sides relate that piles of bodies built up around the various royal and of Philip the Good,

aristocratic standards in the English front line, with Henry himself supposed Duke of Burgundy.

to have protected the wounded body of his brother Humphrey, Duke of (akg-images/Jerome

Gloucester, and to have lost a fleuret from the gold crown of his helmet.

da Cunha)

Despite the fierce nature of the fighting, the first two

French battles were defeated and their leaders

either killed or captured. However,

the final and most controversial act of

the battle was yet to come. When the

English began rounding up their

numerous prisoners the rumour went

round that the as-yet-uncommitted

French third battle was entering the

fray. This third force was so numerous

as to be a threat to the English

position, particularly as they had a

large number of prisoners to their

rear. At the same time a further

French cavalry force attacked the

English baggage and camp, capturing

part of the royal treasure.

33

A view of the Agincourt

These events led to Henry ordering the killing of the French prisoners,

battlefield looking from

apart from those of particularly noble birth. According to the chronicler

Maisoncelle towards the

Jean de Waurin: 'When the king was told no-one was willing to kill his

village of Tramecourt.

prisoners he appointed a gentleman with 200 archers to the task,

At the time of the battle

commanding him that all the prisoners be killed. The esquire carried out

the woods on both sides

the order of the king which was a most pitiable matter. For in cold blood,

of the battle were much

all those noble Frenchman were killed and had their heads and faces cut,

thicker and provided a

which was an amazing sight to see.' It is uncertain how many prisoners were

flank defence for Henry's

killed, but the French chroniclers suggest over 1,000. The French third battle

army. (Author's collection)

never intervened in the battle, slipping away and leaving the field to the

English. Enguerran Monstrelet again describes the reaction:

Whilst his men were busy in stripping and robbing those who had been killed, he

summoned the herald of the king of France, the king at arms called Mountjoye,

The battle of Agincourt

This scene depicts the critical point of the battle. The French men-at-arms have

crossed the field and are embroiled with the English line, while the English archers

are beginning to engage from the flank in an assault that contributed a great deal to

the eventual English victory. In the centre is Henry himself, with his crown on top

of his unvisored great basinet. To his left is Sir Thomas Erpingham, who gave the

order for the archers to fire their first volley, and some way to his right is Humphrey,

Duke of Gloucester. Behind Henry fly the banners associated with Agincourt (from left

to right): Henry's personal standard, the cross of St George, the Holy Trinity, and the

standards of Edward the Confessor and St Edmund. Advancing towards Henry is Jean,

Sire de Croy, who, along with his retinue, made a pact to kill Henry and supposedly

hacked off part of his crown. On the ground in the centre is a French knight struggling

with an English archer, who is trying to stab him through his open visor, while to the

right another French knight has felt the full force of one of the heavy mallets wielded

by the lightly armoured archers.

34

along with several other heralds both

French and English, and said to them,

'It is not we who have caused this killing

but God the Almighty, on account of

the sins of the French, for so we believe.'

Later when he asked them to whom the

victory should be accorded, to him or to

the king of France. Mountjoye replied

that to him was the victory and not the

king of France. Then the king asked him

the name of the castle which he could

BHHHHHHR

see close by. They answered it was called

Agincourt. 'As all battles', the king said,

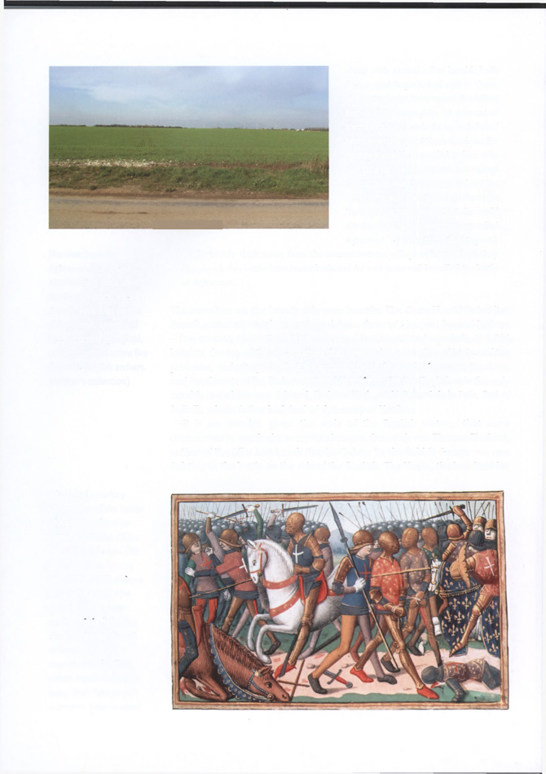

The view from the

ought to take their name from the nearest fortress, village or town where they

Agi n co u rt-Tra m eco u rt

happened, this battle from henceforth and for ever more will be called the battle

road Looking back towards

of Agincourt.'

the French Lines. The

French advanced across

The casualties on the French side were horrific. The

Gesta Henrici Quinti

lists

this ground, which had

French aristocratic fatalities as three dukes - those of Alengon, Bar and Brabant

been recentLy ploughed,

- five counts, more than 90 barons and bannerets and upwards of 1,500

under constant arrow fire

knights. On top of these casualties there were also a number of high-ranking

from the English archers.

prisoners, including Marshal Boucicaut, the Dukes of Orleans and Bourbon,

(Author's collection)

and the Counts of Eu, Richemont and Vendome. On the English side the only

notable casualties were Edward, Duke of York, and Michael de la Pole, Earl of

Suffolk, whose father had died of dysentery at Harfleur.

It is no wonder, given the scale of the English victory, that some

commentators ascribed it to mystical causes. One such was Thomas Elmham,

author of the

Liber Metricus de Henrico Quinto

: 'In the field St George was seen

fighting in the battle on the side of the English. The Virgin, the handmaiden

A late 15th-century

illustration of the battle

of Agin court from

Les

Vigites de Charles VII

by

Martial d'Auvergne (Ms.

francais 5054, fol.ll)

held in the Bibliotheque

Nationale, Paris. This

illustration focuses

on the melee following

the French assault and

depicts an English

man-at-arms leading

bound French prisoners

away, their fate as-yet

unknown, (akg-images)

36