Henry V: The Background, Strategies, Tactics and Battlefield Experiences of the Greatest Commanders of History Paperback (6 page)

Authors: Marcus Cowper

Tags: #Military History - Medieval

much bloud, obtained the Castell, and subdued the residue of Wales vnder the

Kings obeysance.

The fall of Harlech to the prince in March 1409 left the Welsh Revolt largely

subdued. Though Glendower would remain at large and isolated guerrilla

attacks still occurred throughout the principality, no major centres of

resistance remained and Prince Henry felt free to turn his attention towards

England and the growing issues over intervention in France. One benefit of

Henry's years of campaigning in Wales was that he had built up his own

retinue, consisting of men such as Thomas, Earl of Arundel, and Richard,

Earl of Warwick, who would serve him well in his later campaigns in France.

Plans for France

From the year 1409 Prince Henry became increasingly influential in the

affairs of state as part of his role on the king's council. This was partly owing

to the increased disability of Henry IV, who removed himself from a lot of

the day-to-day business of running the kingdom, and partly owing to Prince

Henry's increased political maturity. As he had developed a military retinue,

so he now surrounded himself with a political faction, based largely around

his Beaufort uncles - Henry, Bishop of Winchester, John, Earl of Somerset,

and Thomas, Earl of Dorset. This faction gained power in the royal council

at the expense of the established chancellor, Archbishop Arundel, and the

treasurer, Sir John Tiptoft. The two opposing groups had very different

attitudes to the situation in France.

The state of political affairs in France had become particularly poisonous

following the murder of Louis of Orleans by John the Fearless, Duke of

Burgundy, in November 1407, This solidified factions that had been

developing in the French court into two groups - the Burgundians and the

Armagnacs, named after Bernard, Count of Armagnac. The country was

slipping into a state of near civil war and both sides sought English military

support in their struggles.

Henry and his advisors sought to ally themselves with the Burgundians in

1410-11, sending an expedition under the Earl of Arundel that fought

alongside the Burgundians at the battle of Saint-Cloud in October 1411.

However, in November of the same year Henry IV recovered and Prince Henry

and his faction found themselves out of favour at court and the English

position on France was reversed, with Henry IV and his council signing the

Treaty of Bourges with the Armagnacs in May 1412. This was followed up by

an expedition to Gascony led by Prince Henry's younger brother, Thomas of

Lancaster (now created Duke of Clarence and named the king's lieutenant in

Aquitaine) in August. However, this military effort proved short lived as the

Burgundians and the Armagnacs patched up their differences, leaving Thomas

with no allies in France and instead conducted a wide-ranging

chevauchee

from

Normandy down to Bordeaux, returning after the death of Henry IV.

Despite the king's recovery in November 1411, his health was still weak

and by autumn 1412 he was obviously terminally ill. Prince and king were

reconciled and, following the death of Henry IV on 20 March 1413, Prince

Henry ascended to the throne as Henry V, and could now carry out his plans

for France.

T H E H O U R O F D E S T I N Y

Henry V, like his father and their Plantagenet predecessors, sought to resolve

the English position in France. In particular, he sought the consolidation

of the English possession of the Duchy of Aquitaine in full sovereignty

- something that both the Armagnac and Burgundian factions had been

willing to offer in their negotiations with the English. Open conflict had

broken out again between the two factions in 1413 and so both were anxious

to gain the support of the new English king, sending ambassadors to sound

him out. Henry V was also diplomatically busy, dispatching a high-level

delegation to Charles VI in August 1414 claiming his right to the throne of

France, the restitution of the Angevin territories in northern and

south-western France and the king's daughter, Katherine of Valois, in

marriage along with an enormous dowry of two million crowns. The French,

unsurprisingly, rejected this but negotiations continued and a further English

embassy was in Paris in February 1415. During the same period Henry had

negotiated an agreement with the Duke of Burgundy that he would not

interfere in any attempt by Henry to take the crown of France, though Duke

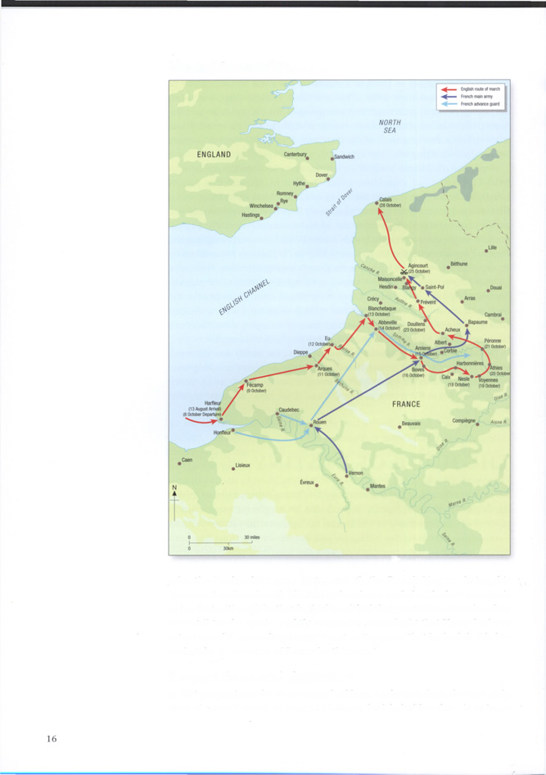

The 1415 campaign

John the Fearless later came to terms with the French king rendering this

agreement null and void. This second embassy ended with the same result

as the first; although both sides had modified their positions somewhat they

were still too far apart - and there remains some doubt that Henry had any

intention of it succeeding in any event as it appears that he had decided to

undertake an invasion of France by this point.

Preparations and departure

In fact preparations for an invasion had been under way from the very early

days of Henry's reign. In May 1413 Henry had forbidden the sale of bows

and other weapons to both the Scots and other enemies, while at the same

time appointing a fletcher as keeper of the king's arrows in the Tower of

London who began to both make and acquire arrows. In September 1414

he also ordered the construction and acquisition of a substantial number

of siege engines and guns, while at the same time banning the export of

gunpowder from the country.

He also started assembling the major fleet that would be required to ship

his army across to France. The king himself possessed a number of ships,

including his 'great ships' - among them his flagship the

Trinite Roy ale -

and

was busy building more, but the amount of shipping required dwarfed

that available and extra shipping was sought from the Low Countries in

early 1415. Henry eventually resorted to seizing all ships - both English and

foreign - in English ports in April 1415, and in the end some 1,500 ships

were assembled to carry Henry's forces over to France.

These forces now assembled on the French coast ready for the invasion.

Henry V's army for the Agincourt campaign was brought together by the

indenture system that had replaced the feudal system of raising troops that

was common earlier in the medieval period. Essentially, Henry entered into

contracts with individual captains who would agree to serve on campaign

along with a specified number of men - their retinue - generally categorized

as men-at-arms or archers. These captains could range from the great magnates

of England, such as the royal dukes, his brothers, who would bring hundreds

of men with them in their retinues, to much smaller groups and even

individuals themselves. Indeed, the Agincourt force is unusual for the

period in terms of the sheer number of indentures issued, with at least

320 individuals recorded. For Thomas, Duke of Clarence's expedition to France

in 1412 there had only been three major retinues - that of Clarence himself,

the Duke of York and the Earl of Dorset.

The balance of the forces assembled had also changed. Earlier in the

Hundred Years War the standard retinue had been fairly equally balanced

between men-at-arms and archers, but by the time of the Agincourt

campaign this balance had shifted dramatically, so that there were now

some three archers for every single man-at-arms. This may have been due

to an appreciation of the combat power of English and Welsh archery on

the battlefield, something that Henry must have personally appreciated

following his experiences at the battle of Shrewsbury, but it might also have