Her Every Wish (13 page)

Authors: Courtney Milan

Adrian Hunter has concealed his identity and posed as a servant to assist his powerful uncle. He's on the verge of obtaining the information he needs when circumstances spiral out of his control. He's caught alone with a woman he scarcely knows. When they're discovered in this compromising circumstance, he's forced to marry her at gunpoint. Luckily, his uncle should be able to obtain an annulment. All Adrian has to do is complete his missionâ¦and not consummate the marriage, no matter how enticing the bride may be.

Lady Camilla Worth has never expected much out of lifeânot since her father was convicted of treason and she was passed from family to family. A marriage, no matter how unfortunate the circumstances under which it was contracted, should mean stability. It's unfortunate that her groom doesn't agree. But Camilla has made the best of worse circumstances. She is determined to make her marriage work. All she has to do is seduce her reluctant husband.

From Chapter One

L

ady Camilla Worth

had dreamed of marriage ever since she was twelve years of age.

It didn't have to be marriage. It didn't have to be romantic. Sometimes she imagined that one of the girls whose acquaintance she madeâhowever brieflyâwould become her devoted friend, and they would swear a lifelong loyalty to one another. She'd daydreamed when she lived in Leeds about becoming a companionâno, an almost-granddaughterâto an elderly woman who lived three houses down.

“What would I ever do without you, Camilla?” old Mrs. Marsdell would say as Camilla wormed her way into her heart.

But Old Mrs. Marsdell never stopped frowning at her suspiciously, and Camilla had been packed up and shunted off to another family long before she'd had a chance to charm anyone.

That was all she had ever wanted. One person, just one, who promised not to leave her. She didn't need love. She didn't need wealth. After nine times packing her bags and boarding trains, braving swaying carts, or even once, walking seven miles with her aging valise in tow⦠After nine separate families, she would have settled for tolerance and a promise that she would always have a place to stay.

So of course she hoped for marriage. Not the way she might have as a child, dreaming of white knights and houses to look over and china and linen to purchase. She hoped for it in the most basic possible terms.

All she wanted was for someone to choose her.

Hoping for so little, she had believed that surely she could not be disappointed.

It just went to show. Fate had a sense of humor, and she was a capricious bitch.

For here Camilla stood on her wedding day. Wedding night, really. Her gown was not white, as Victoria's had been. In fact, she was still wearing the apron from the scullery. She had no waiting trousseau, no idea what sort of homeâif anyâawaited her. And she'd still managed to miss out on her dreams.

Her groom's face was hidden in the shadows; late as this wedding was, on this particular night, a few candles lit in the nave did more to cast shadows than shed illumination. He adjusted his cuffs, gleaming white against the brown of his skin, and folded his arms in disapproval. She couldn't see his eyes in the darkness, but his eyebrows made grim lines of unhappy resignation.

It might even have been romanticâfor versions of

romantic

that conflated

foolhardy

with

funâ

to marry a man she had known for only three days. And what she knew of the groom was not terrible. He'd been kind to her. He had made her laugh. He had evenâonceâtouched her hand and made her heart flutter.

It might have been romantic, but for one tiny little thing.

“Adrian Hunter,” Bishop Cantrell was saying. “Do you take Camilla Worth to be your wife? Will you love her, comfort her, honor and protect her, and forsaking all others, be faithful to her as long as you both shall live?”

She would have overlooked the gown, the trousseau, anything. Anything butâ¦

“No,” said her groom. “I do not consent to this.”

That one tiny little thing. Like everyone else in the world, her intended didn't want her.

Behind him, Rector Daniels lifted the pistol. His hands gleamed white on the barrel in the candlelight, like maggots writhing on tarnished steel.

“It doesn't matter what you say,” the man said. “You will agree and you will sign the book, damn your eyes.”

“I do this under duress.” His words came out clipped and harsh. “I do not consent.”

Camilla shouldn't even call him her intended.

Intent

on his part was woefully lacking.

“I'm sorry,” Camilla whispered.

He didn't hear her. Maybe he didn't care.

She wouldn't have minded if he didn't love her. She didn't want white lace and wedding cake. But this wasn't a marriage, not really. She was being wrapped up like an unwanted package again and sent on to the next unsuspecting soul.

After being passed onâand onâand onâand onâafter all these years, she had no illusions about the outcome in this case.

The candlelight made Mr. Hunter's features seem even darker than they had in the sun. In the sun, after all, he'd smiled at her.

He didn't smile now.

There it was. Camilla was getting married, and her husband didn't want her.

Her lungs felt too small. Her hands were shaking. Her corset wasn't even laced tightly, but still she couldn't seem to breathe. Little green spots appeared before her eyes. Dancing, whirling.

Don't faint, Camilla,

she admonished herself.

Don't faint. If you faint, he might leave you behind, and then where will you be?

She didn't faint. She breathed. She said yes, and the spots went away. She managed not to swoon on her way to sign the register. She did everything except look at the unwilling groom whose life had so forcibly been tied to her own.

She followed him out into the cold winter evening. There would be no celebration, no dinner. Behind her back, she heard the clink of coins as the bishop turned to Mr. Hunter.

“There's an inn a mile away,” the man said. “They might allow you to take rooms for the night. Don't expect that I'll give you a character reference.”

Mr. Hunter made no response. He just started walking down the road.

That was how Camilla left the tenth family that had taken her in: on foot, at eleven at night, with a chill in the air and the moon high overhead. She had to half-skip to keep up with her newâ¦husband? Should she call him a husband?

His long legs ate away at the ground. He didn't look at her.

But halfway to the inn, he stopped. At first, she thought he might finally address her. Instead, he let his own satchel fall to the ground. He looked up at the moon.

His hands made fists at his side. “Fuck.” He spoke softly enough that she likely wasn't supposed to hear that epithet.

“Mr. Hunter?”

He turned to her. She still couldn't see his eyes, but she could feel them on her. He'd lost his position and gained a wife, all in the space of a few hours. She didn't imagine that he was happy with her.

He exhaled. “I suppose thisâ¦is what it is. We'll figure this mess out in the morning.”

The morning. After the wedding came the wedding night. Camilla wasn't naïve. She just wasn't ready.

How had her life come to this?

Ah, yes. It had started three days ago, when Bishop Cantrell had arrived on her doorstep with Mr. Hunter in towâ¦

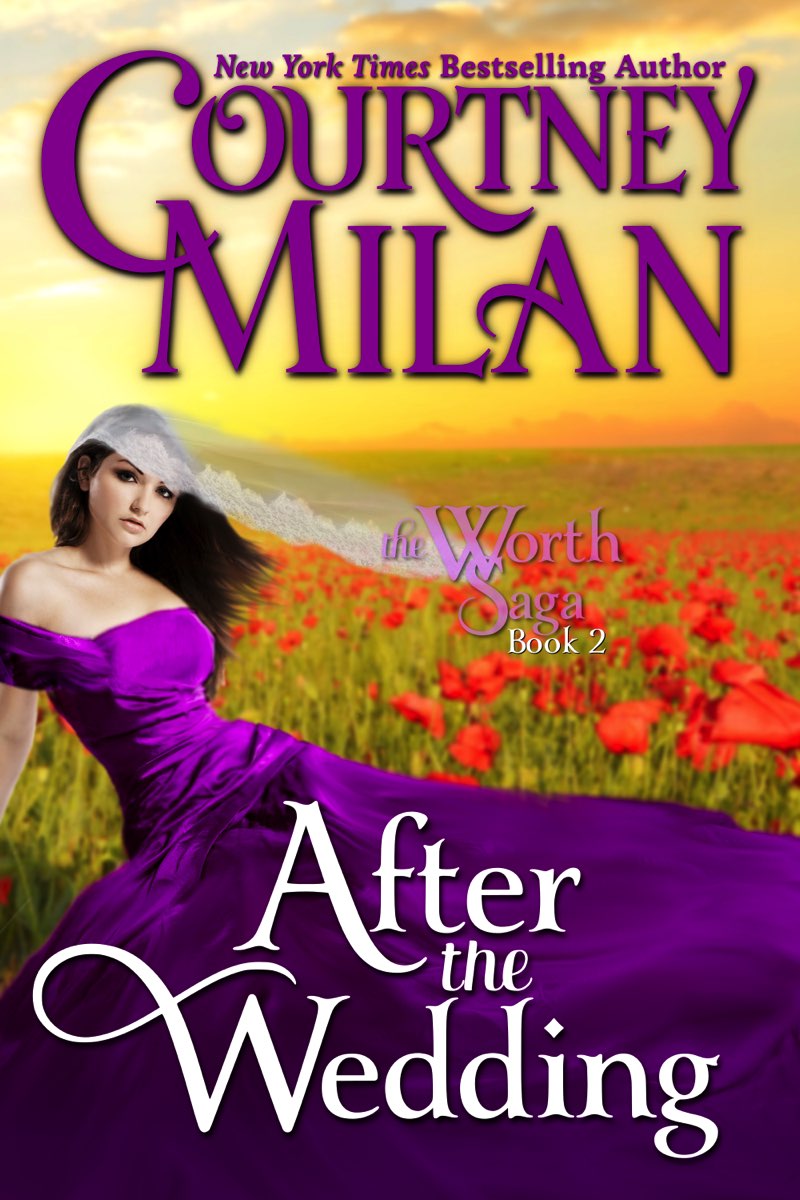

After the Wedding

will be out in late 2016.

I

had

the initial idea for this book a long time agoâin 2011, when I was doing research for

The Duchess War

. I ran into a bit of something in the Leicester archives advertising a charity loan for young residents of the parish looking to start a new trade or business. I remember reading the language very carefully and thinking to myself, huh. They don't say you have to be a man to apply.

I thought I knew precisely what to do with that. Except the problem was finding an appropriate hero. I tried someone who was in the competition against Daisy, but unfortunately, didn't like that dynamic. I tried one of the judges. I tried someone who was tasked with persuading her to withdraw. None of those things worked for me for a number of reasons.

And then, when I was writing,

Once Upon a Marquess

, a random minor character appeared on the screen and I called him Crash. I don't know why. It's not exactly a name one would normally use. But as soon as I wrote the nameâCrashâI figured out that his real name was Nigel, and everything sort of followed from there.

The word “bicycle” was in use back in 1866, although rarely; I've chosen to use the word “velocipede” almost exclusively because the velocipedes of 1866 were dissimilar from today's bicycles in a number of ways. For one, there was no bicycle chain in most production models. There were definitely no shocks. And bicycle helmets are an incredibly recent invention. Nonetheless, the bicycle was an amazing invention, and it became all the rage late in the 1860s. Crash would have been perfectly positioned to take over the craze.

Britain was an empire, and for a very long time, one of the chief products that empire sought after was labor. It was involved in the African slave trade for a very long time, until slavery was outlawed in Britain itself in 1772, followed by the abolition of the trade in slaves in 1807, and finally by slavery in British colonies in 1833. This did not end the thirst for cheap labor. In lieu of African slaves, Britain would impress sailors (both domestically and internationally). It was one of the global players engaged in what was colloquially known as the “pig trade”âwhich involved Chinese laborers who were indentured servants, where some of them entered their period of servitude more involuntarily than others. And of course, Britain ruled over numerous colonies where cheap, abundant, exploitable labor was usedâIndia being one of them.

These workers were often impressed into doing grunt work for the merchant marines. As you can imagine, worker safety was not highly valued, and workers who were injured on the job back in those days had little by way of regulatory protection. The global empire of Britain is littered with stories of sailors from around the world being marooned in various ports. If they weren't able to work to the rigorous standards of an ocean-going vessel, they might find themselves far from home with no way to return.

Britain didn't obtain racial data in its census for quite some time, and so reconstructing questions like how many people of color were in Britain in the latter half of the nineteenth century is difficult. But how many is not relevant to the question of their general existence: They were absolutely there, and it's probably reasonable to assume that those who ended up in London for one reason or another tended to band together.

When I was doing research for Talk Sweetly to Me, I read an essay about how a photographer in the 1920s who was taking pictures of working-class people discovered a tiny neighborhood in Bristol near where the slave ships had docked over a century before. In this area, nearly everyone was some shade of brown, the result of people who had been stranded generations ago and had intermarried with each other and the local population and various sailors of every ethnicity who had wandered by.

When I wrote Crash and his aunt and their group of friends, I was imagining that sort of Bristol neighborhood in London. Given the number of people from around the world who ended up stranded in London, such a place would have to exist.

When Crash says that much of England would refer to his aunt and his friends as whores, this is not meant to be descriptive as many people would understand that term. One of the main problems that authorities had in the 1860s is that it was difficult to corral the spread of STDs because it was hard to tell who was involved in sex work and who wasn't. This is in part because upper-class English gentlemen were jerks who thought they could have sex with anyone poor, and in part because prostitution just didn't work the way they thought it did. There were some people who only earned a living in prostitution, but a huge number of people who might be classified as sex workers back then had a regular job, and then maybe a man or three on the side. Many authorities basically assumed that anyone working jobs that earned little enough money had to be involved in prostitution on the side.

Finally, a note on two items mentioned in the book. The velocipede really did start to become popular at the end of the 1860s, and it has basically never stopped since, despite significant advancements in transportation technology. Crash would have gotten his foot in the door right at the start. Crash is also (basically) right when he says that you're more stable on a bicycle the faster you go. For the same reason, tops wobble less when you spin them faster. It's a physical phenomenon known as precession. I didn't want to go into too much detail, because obviously the faster you go, the more you can hurt yourself, and bicycle helmets were a shockingly recent invention, compared to the history of the bicycle.

Second, there is such a thing as a carbolic smoke ball, and that (like other random things that show up in my book) is a joke between me and ten thousand law students who will all say, “ARGH, CARBOLIC SMOKE BALLS!” There's a famous case from 1892 involving an advertisement for a carbolic smoke ball.

The basic idea behind a carbolic smoke ball was that the ball contained carbolic acid, which interacted with the air and filtered it. The makers of the ball claimed it would filter out, say, influenza germs. Like about 95% of the purveyors of Victorian-era medical equipment, they were totally wrong. The actual Carbolic Smoke Ball Company featured in the 1892 advertisement didn't exist in 1866, but upon research, I did find references to early inventions that were basically carbolic smoke balls that were period. So I hope you enjoy it.