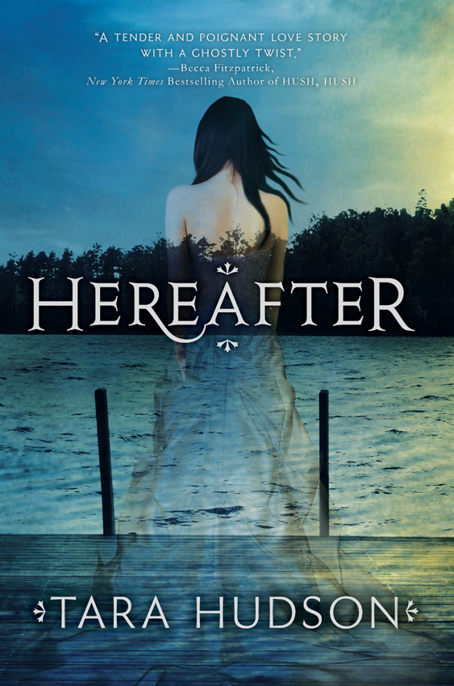

Hereafter

Authors: Tara Hudson

Hereafter

Tara Hudson

To Robert. In an instant. In a heartbeat.

Contents

I

t was the same as always, but different from the first time.

It felt as if my sternum was a door into which someone had roughly shoved a key and twisted. The door—my lungs—wanted to open, wanted to stop fighting against the twist of the key. That primitive part of my brain, the one designed for survival, wanted me to breathe. But a louder part of my brain was also fighting any urge that might let the water rush in.

The black water seized and scrambled and found purchase anywhere it could. I kept my lips pressed together and my eyes shut tight, though I desperately needed sight to escape this nightmare. Yet the water still entered my mouth and my nose in little seeps. Even my eyes and ears couldn’t hold it back. The water wrapped around my arms and legs like shifting fabric, tugging and pulling my body in all directions. I was buried under layers and layers of slippery, twisting fabric, and I wasn’t going to claw my way free.

I’d struggled too long, fought too hard, and now my body was weakening from the lack of oxygen. The flail of my arms toward what I assumed was the surface became less exaggerated, as if the invisible fabric around them had thickened. I literally shook my head against the urge to breathe. I shouted

No!

in my head.

No!

But instinct is a slippery thing, too—ultimate and untrickable.

My mouth opened and I breathed.

And as I always did, except for the first time I’d experienced this nightmare, I woke up.

My eyes remained closed and I continued to gasp. This time my gasp brought hysterical gulps of air, but not the brackish water that had flooded my lungs and stopped my heart during that first nightmare.

Now the air was useless, purposeless in my dead lungs. I nonetheless felt a dull joy at its presence: although my heart no longer beat, the air meant I was no longer drowning.

Still, I felt a little silly for being afraid. After all, it’s not like you can die twice.

And I was already dead, that much was certain.

It had taken me awhile to accept the fact, perhaps years—time became a very uncertain thing in death. Years of wandering, confused and distracted by every sight and sound. Screaming at passersby, begging them to help me understand why I was so lost or even just to acknowledge my presence. I could see myself—bare feet, white dress, and dark brown hair that had dried into thick waves—but others couldn’t. And I never saw another person like myself, someone dead, so there was really no point of comparison.

The nightmares were what made me finally see, and accept, the truth.

At first nothing in my wandering existence brought back memories of my life, nothing but the elusive familiarity of the woods and roads I wandered.

But then the nightmares began.

I would suddenly and without warning fall into periods of unconsciousness. During them I would drown again. Only after the first few nightmares did I see them for what they were: memories of my violent death.

So the memories of my death had returned. Yet only a few memories of my life came with them: my first name—Amelia—but not my last; my age at death—eighteen—but not my date of birth; and, of course, the fact that I’d apparently thrown myself off a bridge into the storm-flooded river below. But not the reason why.

Though I couldn’t remember my life and what I’d learned in it, I still had some vague recollections of religious dogma. The few tenets I remembered, however, certainly hadn’t accounted for this particular kind of afterlife. The wooded, dusty hills of southeastern Oklahoma weren’t my idea of heaven; nor were the constant, narcoleptic revisits to the scene of my drowning.

The word “purgatory” would come to mind after I woke from each nightmare. I would play out my horrific little scene and then I would wake up, gulping and sobbing tearlessly, in the exact same place each time. It wouldn’t matter where I’d been wandering when I went unconscious—an abandoned railroad track, a thick grove of pines, a half-empty diner—my destination was always the same. And each time the nightmare ended, I would wake in a field. It was always daylight, and I was always surrounded by row upon row of headstones. A cemetery. Probably mine.

I never waited around to find out.

I could have searched for my headstone maybe. Could have learned more about myself—about my death. Instead, I’d pull myself up from the weeds and dash for the iron gate enclosing the field, running as fast as my nonexistent legs would carry me.

And so it was with my existence: a montage of aimless wanderings; an occasional word spoken to an unhearing stranger; and then the nightmares and subsequent hasty escapes from my waking place.

Until this nightmare.

This nightmare had started the same. And, just as it always did, it ended with a terrified awakening. But this time when I finally opened my eyes, I didn’t see the sunlight of a neglected cemetery. I saw only black.

The unexpected darkness brought back the terror, the frantic gasping. Especially since, after what would have been only one beat of my still heart, I recognized my location.

I was floating in the river again.

My renewed gulps, however, didn’t drag in muddy water that surrounded me. My body was still as insubstantial as it had been before this nightmare. It floated, unaffected by the drag and pull of the angry water. This time things were different, although the dark, twisting scene looked almost the same as it did in each of my horrible dreams.

Almost.

Because this time I wasn’t the one drowning.

He was.

M

y first impression of the scene was wrong. The water wasn’t entirely black. Faint light shimmered above the surface—moonlight, maybe; it was too grayish to be sunlight. Below me two muted yellow beams seemed to rise from the depths of the river.

No, not rise. The beams pointed upward, but they were retreating. I spared a quick glance at them. They came from a huge, dark shape just below me. The shape—a car, its headlights beaming into the darkness—floated downward with an eerie slowness.

I shook my head. I didn’t really care about the car; my attention was riveted on the boy illuminated in its headlights.

His body had shaped itself into a kind of

X

, arms floating limply upward and sneakered feet dangling. His head hung down, but I could tell his eyes were closed.

This boy didn’t flail or struggle, and I had a sudden, sickening realization. The boy was unconscious. Not the kind of unconsciousness that torments the dead, but the kind that kills the living.

If he didn’t wake up, this boy was going to drown.

Without another thought, I swam to him as fast as I could. When I reached him, I could see his face fully. He was young, no older than I was when I died. His face looked peaceful in its stillness. He was strikingly handsome. I could see that, even under the water. His dark hair floated above his head almost lazily, considering the current. An involuntary and silly image sprang to my mind: his outspread arms resembled wings. Useless wings, at that. I wondered, almost idly, whether my arms had resembled his when I died.

My thoughts, then, were as sudden as they were fierce. This boy couldn’t die. I couldn’t watch him die. Not here, not like this.

I began to grasp at him, frantically trying to pull at his clothes and his limbs. To drag him to the surface. I tugged at his long-sleeved shirt and his jeans, even at his dark hair.

I pulled and pulled, but of course nothing happened. My stupid, dead hands couldn’t touch him, couldn’t save him. It was like struggling in the water on the night of my death—not a damn thing that I did would have any effect on the outcome. I was impotent, ineffective, and never more aware of the fact that I was dead.

Soon I started weeping my tearless sobs and pressed both my hands against his chest. As we sank deeper into the river, I became acutely aware of something: the sound of his slowing heartbeat.

As far as I knew, I possessed no supernatural senses whatsoever. Although some of my human senses had survived my death—my sight and hearing, obviously—I could no longer smell, taste, or feel anything in the living world. My remaining senses hadn’t dulled, but they certainly hadn’t improved, either.

So the sound of his heartbeat shocked me. I shouldn’t have heard it so well, but I did. Even with a foot of water between us and with my no-better-than-human hearing, I could hear his heartbeat as clearly as if I’d pressed a stethoscope to his chest.

I wondered whether this had something to do with death. With

being

dead. Perhaps the dead could hear one of our own approaching, racing toward us. Or slowing toward us, in his case.

The boy and I continued to sink; and as we did so, his fragile heart beat unevenly toward its end. Each thud came slower than the one before it, until finally—

His heart stuttered once. Twice. And then I couldn’t hear it anymore. A tiny bubble escaped the corner of his lips and floated upward.

I screamed. I screamed as I did in the first flush of death, angry and humiliated at my own lack of power. I screamed and slapped my useless hands against his chest.

At that moment his eyes opened.

He looked to the left and the right, taking in his surroundings. Then he looked at me. He looked right into my eyes.

I froze. Could he . . .

see

me?

He smiled, and then suddenly reached out his hand to place it upon my cheek. I felt his skin, warm on mine. Without thinking, I put my hand over his. His smile widened when I touched him.

He

did

see me.

He saw me, he saw me, he saw me.

My still, unbeating heart soared. And then so did his.

His heart—the one I’d just heard dying—stuttered, and stuttered again. The renewed beat sounded slow and uneven at first, but quickly it began to steady itself.

He looked down at his chest and back up at me, eyebrows arched in surprise at the sound coming from within him.

Then he coughed. The motion shook his whole body and sent bubbles flying out of his mouth.

He began to kick and flail. As he flailed, I realized I could no longer hear his heart. It was silent, at least to me. Yet he was thrashing about, fighting against the dark water. He continued to cough violently as his lungs spasmed back to life. Through the churning water, I could see his expression. He looked angry, terrified, and desperate.

I recognized that look. I had once

felt

that look. This boy was alive. He was alive, and he didn’t want to die.

“Swim!” I screamed at him suddenly. “Up! Out!”

He didn’t look at me, but he began to scissor his legs and grab at the water above his head as if he were climbing out of a pit. Unlike my efforts on the night of my death, however, his struggles worked. He began to float upward, toward the surface of the river.

I’d never felt a wave of relief like this. Not in a million nightmare-wakings. Not in a million of those gasps that proved I was no longer drowning.

“Up!” I screamed again, this time with joy.

He continued to claw his way up, not once looking back at me or at the sound of my voice as I followed him effortlessly. Perhaps to him I was once again other, different

—

dead. For the moment, I couldn’t have cared less. He would live. He wouldn’t die in this cold, wet pit like I had. That was more than enough.

It felt like an eternity until he broke the surface of the river, but he did. In the night air, he choked and sputtered and gasped, flapping his arms against the water as if he were trying to fly away from it.

I floated beside him, entirely unaffected by the current or the churning his movements had created. When he sucked in a huge breath of air, I actually laughed aloud and clapped my hands together. Then I clapped my hands over my mouth. I’d never laughed. Not once since my death.

“Josh! Josh!”

The unfamiliar voice startled me. Someone had called out across the river to us. Well, to the boy anyway. I turned away from him, almost unwillingly, and saw a cluster of figures on the riverbank behind us.

“Josh!” a girl’s voice screamed. “Oh Jesus, Josh, please! Someone help him!”

I turned to the boy, who was still coughing and flailing.

“Josh?” I asked. “Are you Josh?”

He didn’t answer.

“Well, Josh or not Josh, I know you’re tired. God knows I know. I know you probably can’t hear me, either. But you’ve got to swim toward those voices. Do you understand?”

For a second he didn’t react. Then, with painful slowness, he began to move his arms. The movements didn’t exactly qualify as swimming, but they were enough to start pushing his body through the water.

As he got closer, the screams from the shore grew louder. In them I could almost make out a rational thread of conversation concerning the plan to pull him out of the river.

But really, I wasn’t listening to the people on the shore. I was watching the boy swim, closer than I’d ever watched anything in my existence. I found myself praying for the first time since my death. Praying that he made it safely to the shore; praying that he didn’t give up and let the current take him.

“Please,” I whispered as I followed him. “Please, let him make it.”

This boy proved much stronger than I ever had. For several more agonizing minutes, he fought his way through the current. Finally, he was close enough so that someone was able to grab his arm and half swim, half drag him to the shore.

Cries of both joy and fear rose up from the crowd that had gathered on the grass embankment and the bridge above us. A man, the one who had pulled the boy from the water, stretched the boy out upon the muddy red riverbank. As I rose out of the water and walked onto the shore, I could see the man flutter his hands over the boy’s body, checking for some sign of life.

The boy instantly rolled over, coughed once, and began to vomit water. Audible sighs of relief rose up from the crowd. Their faces were illuminated by headlights from the cars parked in a jumble on the grass as well as on the bridge. The onlookers’ expressions varied from tense to excited to scared.

“Josh. Josh,” they called like a chorus.

They all seemed to know his name.

It was then that I noticed the multicolored flash of lights coming from the emergency vehicles that had formed their own sort of crowd behind the bystanders on the bridge. Within what seemed like only seconds, two uniformed paramedics had made their way down the embankment and knelt beside the boy, doing their own, more effective sort of fluttering over him. Within less than a minute after that, the boy—my boy, if I was honest in my suddenly possessive thoughts—was placed on a gurney and hoisted across the bank, then up toward an ambulance. The crowd surged forward with the paramedics, and I lost sight of him.

That should have been the end of the ordeal. Yet I couldn’t stand still. I couldn’t watch strangers take away the only living person to see me. My boy. My Josh.

Determined, I pushed through the crowd. They couldn’t see or feel me, of course, but I still had to fight to find a clear path.

By some miracle I made it through. I shoved in between two figures and suddenly found myself at the side of the gurney just as the paramedics began to raise its wheels so they could slide it and its passenger into the ambulance.

I leaned over the boy. He looked pale in the moonlight, his face gaunt and drawn. For some reason I had to hold back a sob.

“Josh?” I moaned, unsure of what to do. Unsure of everything.

He opened his eyes then. Dark-colored eyes—too dark a color to identify at night. He looked at me and held my gaze in the moment before the paramedics moved him out of my sight, possibly forever.

“Joshua,” he croaked, his voice rough from the river water. “Call me Joshua.”

Then the gurney was shoved into the ambulance, the doors slammed shut, and he was gone.

I stood there on the riverbank, motionless. Some of the onlookers remained after the departure of the ambulance, milling around to discuss what I could only assume was the near tragedy. I barely noticed when the last member of the crowd left and the last set of headlights disappeared into the darkness of the night. I wasn’t really paying enough attention to hear or see anything going on around me.

What I saw instead were his eyes, looking right into mine. What I heard was his voice . . . talking to me? Yes, I’m sure he’d been talking to me. No one had asked him to identify himself as they loaded him into the ambulance. He’d had no reason to give his name to anyone but me. Most of the crowd seemed to know him. Maybe they’d known him all his life. Maybe they’d sensed, as I had, how important he was.

Of course I knew his importance now. I knew it deep in my suddenly very awake core. I knew nothing about him—not his age, his last name, the way his voice would sound if it spoke my name. But I knew things had changed for me. They had changed forever.