Hero of the Pacific (11 page)

Read Hero of the Pacific Online

Authors: James Brady

Manila John had announced prematurely to Paige in May that they had that “ticket home.” But in July he was still there, training troops, making formation every morning, doing whatever it was he did each night as the weeks passed. And the Pacific war went on. For a time it wasn't really a Marines war at all. The only substantial fighting by late May was in far-off Attu in the Aleutians where the Japanese had dug in and the American Army, the GIs as they were now widely called in the headlines, were taking significant losses trying to dig them out. The Aleutians were cold and windswept, isolated and only thinly populated, really not very strategically important. But they were part of territorial Alaska and therefore American ground. And that was sufficient emotional and political reason to take them back, regardless of the cost. Fighting continued in the Solomons, though not on the 'Canal, and it was mostly a naval fight and an aviator's war. Henderson Field remained vital, and the once tiny, beleaguered, potholed little airstrip was now capable of launching a hundred American warplanes at a time to harass and sink Japanese shipping, to shoot down Zeroes, to take the bombing war to other of the Solomons still in Japanese hands. Henderson Field had indeed been worth fighting for.

On May 30, Attu fell. The ghastly count read 600 Americans dead, 1,200 wounded. True to their tradition, only 28 Japanese troops, all of them wounded, survived, with 2,350 dead, many of those suicides. Across the world the Russians were chewing up the Germans in fierce spring fighting, Tunisia still held out against the Allies, while plans firmed up for the invasion of Sicily, Patton and Monty and all that. In the Atlantic we were now sinking German U-boats in almost equal numbers to Allied losses in the convoys.

Closer to Australia and New Zealand where the Marines like Basilone trained, played, and waited, the island-hopping resumed with GIs and Aussies fighting in increasing numbers on New Guinea, and the 4th Marine Raider Battalion prepared to land on New Georgia, the first real confrontation of U.S. Marines and Japanese infantry since Guadalcanal was finally “secured,” Marine terminology for “job well done.” As was said in wise-guy USMC lingo, “There's no cure like see-cure!”

Basilone, in the Jerry Cutter and Jim Proser account, takes up the story: “We were back on maneuvers, gearing up for some scheme they were cooking up with Mac's [Douglas MacArthur's] 6th Army stationed up in Brisbane, probably the same swamp we left behind [an ironic note of delight to the Gyrenes, surely]. The wheels were turning again, slowly. Each day new equipment arrived and more shaved-head âboots' a few weeks out of Basic filled out our ranks. It was a good mix in a way because we could fill in the new boots on the real world of jungle warfare, not what they heard in scuttlebutt. I wished somebody like us had been there on the 'Canal to take us aside and tell us the real dope. I could tell we were going to keep a few of these kids from getting killed because they listened to every word and we never had to tell them something twice.”

Reading such sensible, and even rather noble, stuff from Manila John, you have to wonder as he drilled these kids on his beloved heavy Brownings, stripping and reassembling them in the dark, had he earned a few bob competing with them, as he had done during his Army days, stateside as a Marine, or on Samoa?

There is another reference to home: “George [another of John's brothers] had joined the Marines. He was headed to the Pacific, too, so maybe we'd meet up somewhere. Everyone was doing fine and they were praying for me every day. The whole town was. That was supposed to make me feel better because a lot of angels were watching over me. If that was true, I'd have a few things I had to answer for when I got to heaven.

If

I got there.”

If

I got there.”

There is a new, uncertain tone here, pensive, less impulsive. He was getting older, maybe growing up. In May, when he was awarded the medal, he'd declared, almost in glee, that the famed medal meant a “ticket home.” That moment was now forgotten, the jubilation vanished. He was reconciled to the idea of going back into combat, taking on another campaign, landing on another hostile beach. That was what Marines did. And Basilone was certainly a Marine before he was ever a Medal of Honor laureate. Paige would be going back to war, Puller would be going, Bob Powell and the rest of them, and this “mix” of youngsters fresh out of boot camp and old stagers from the 'Canal would be going to the war. And why wouldn't Manila John be with them?

The warrior in Basilone seemed at peace with the notion of another fight. He was not at all restive or apprehensive.

Suddenly in Melbourne, there arrived new orders. Manila John was being pulled out of his battalion, was leaving the division and shipping out for the States, where an entire country at war was about to meet and embrace him. Many there were as yet unaware of just who the guy was, where he came from, and what he had done in his short and eventful life beyond killing people and winning medals.

If you really want to know about Johnny Basilone, though, you start with a small town in New Jersey.

PART TWO

HOMETOWN

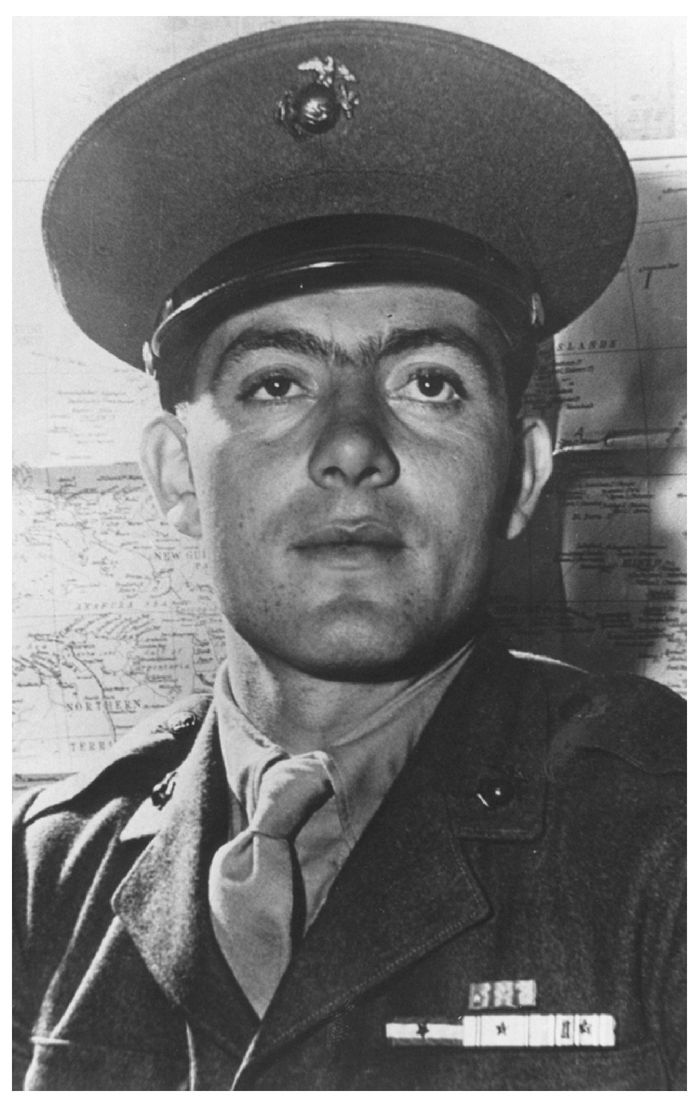

Basilone in his service uniform.

10

John Basilone's family boasted no martial tradition, and John was a fairly unruly kid, not overly given to discipline, so he had no reason to believe, not then, that he just might have been born to soldier.

In fact, his boyhood was unremarkable small-town stuff. According to Bruce Doorly: “Basilone's mother Dora Bengivenga grew up in Raritan, born in 1889 to parents Carlo and Catrina, who had recently emigrated to America from Naples, Italy. Carlo was a mill worker. In 1901 Dora's parents purchased a house in Raritan at 113 First Avenue for $500. This would later be where John Basilone grew up. The house was built in 1858 and in 1901 was a single family home, but later additions would [make] it a two-family house. John's father, Salvatore Basilone, had come to America from just outside Naples in 1903 when he was 19. He went to work in Raritan and made friends among the other Italian Americans.”

There were church parties and neighborhood gatherings, and it was at one of these that Salvatore met Dora. They dated for three years, saved some money, got married, and moved in with Dora's parents on First Avenue. Salvatore worked as a tailor's assistant, and their first five children were born in the family home. Looking for more work than Raritan offered, they moved north to Buffalo, New York, where young John, sixth of the Basilone children, was born not in a proper hospital but at home, very much in the family tradition, on November 4, 1916. But the Buffalo interlude was brief. Whether it was the long winters or a slump in the tailoring trade, the family returned to Raritan in 1918. By now Salvatore had a tailor shop of his own, and they were living in one-half of the two-family house. There was one bedroom downstairs for the parents, and two more upstairs, one for the girls, the other for the boys. There were usually several kids to a bed and the house had a single bathroom. The Basilones certainly weren't living grandly.

Growing up, John enjoyed the usual scrapes, black eyes, tossing rotten tomatoes, swimming “bare-ass” in the Raritan River, silent movies, later talkies, mostly westerns and serials, in a local movie theater kids called the “Madhouse” for its boisterous matinees punctuated by loud boos, hisses, cheers, and thrown popcorn. Half a dozen sources recall one Basilone caper that was hardly ordinary. At age seven and eager for adventure, he climbed a pasture fence and was promptly chased and knocked over by a bull. No damage was done to either boy or bull.

Doorly reports that St. Bernard's parochial school yearbook described John as “the most talkative boy in the class” and that “conduct was always his lowest mark.” His sister Phyllis admitted the boy had difficulty in grammar school, couldn't seem to “buckle down” to his studies. When he graduated, at age fifteen (most graduated at thirteen or fourteen), Basilone opted to drop out, not to go on to high school. He confessed, apparently to his adviser, Father Amadeo Russo, that he might be a “misfit,” that school just wasn't for him. John's father objected strongly to the idea of working at the local country club, but the boy assured him he could make a little money caddying at the club, shrewdly pointing out he'd be outdoors getting exercise and plenty of fresh air. At the Raritan Valley Country Club, according to the Cutter and Proser book, it was while caddying for a Japanese foursome that young John had one of his early “premonitions,” of a war one day when the United States would have to fight the Japanese. No one else in Raritan can recall Basilone's ever having spoken of such a premonition. “He wasn't that sort of fellow,” one said. On rainy days or when caddying was slow, John and the other boys played cards. John turned out to be a natural at it, becoming a lifetime gambler, canny and adept, winning more than his share of the usually small stakes.

When the golf season ended, John got a “real” job, working as a helper on a truck for Gaburo's Laundry at the corner of Farrand Avenue in Raritan, delivering clean clothes, a job he actually held on to for a year before being canned for sleeping on the job. According to Doorly, future Raritan mayor Steve Del Rocco, who knew Basilone, called him “a happy go lucky . . . [who] enjoyed everything he did.”

But John was restless. And with his lack of education and difficulty with books, in a down economy, at some point he must have concluded that going into the Army (a private received twenty-one dollars a month; a uniform; a pair of stout, hard-soled shoes; and three squares a day) might be a way of escaping depressed and jobless Raritan. Not yet eighteen, he needed parental approval, and that took considerable convincing. According to sister Phyllis, their father, Salvatore, “tried to reason with him. âJohnny, you're crazy. You're only a kid. There's no war, why do you want to join the Army?'” Raritan was a small town, and John's mother was reluctant to see her boy leave home and go out into a very large and unknown world. He argued, though without any evidence, “I'll find my career in the Army.”

Wrote Phyllis, “He explained to papa that with the Depression all about us, it was almost impossible to get a job. Army life might be just what he was looking for, he said. Then again, when his enlistment ran out, conditions might be better.” On that point, Salvatore, an employed tailor but very well aware of the lousy job market, who'd been pressuring John to start a career in something,

anything

, reluctantly had to agree with his son. Doorly writes that the senior Basilones may have concluded the military could be “a good match” for a strong, active, out-of-doors kid like their son.

anything

, reluctantly had to agree with his son. Doorly writes that the senior Basilones may have concluded the military could be “a good match” for a strong, active, out-of-doors kid like their son.

We know to the day the date on which John would later join the Marine Corps, but there is a debate on when, even in what year, he earlier joined the prewar U.S. Army in the mid-1930s. Doorly believes John joined up in June 1934. Cutter tells me that by his reckoning, John enlisted “about three months before he turned eighteen [on November 4], which would have been August of '34. I know his parents had to sign on.” His Marine Corps records insist he had joined the Army early in 1936. His 1935 Army service in the Philippines, thoroughly documented, indicates the Marine data is incorrect. But the military records that might solve this small and perhaps unimportant question were destroyed by fire in 1973 at the Military Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, where the archives were held. According to Marine historian Bob Aquilina, Marine and U.S. Navy records went untouched in the fire but Army records of the time were burned.

There may have been additional arguments within the family about John's enlistment, some fits and starts along the way, since with the requisite records missing, some contradictory evidence suggests that John didn't actually enlist until he was nineteen. The Marine Corps, which apparently keeps files on just about everything, even the other military services, reports on John's military service record that he joined the Army on February 5, 1936, and served on active duty with consistently excellent fitness reports until being discharged back into civilian life and the U.S. Army Reserve on September 8, 1939. Since there is reasonable proof that as a young soldier still on his first enlistment John arrived in the Philippines in March 1935 to start a two-year overseas tour of duty, we can conclude that, at least this once, the Marine Corps got it wrong.

All we get is a fanciful line or two supposedly from “Johnny” to Phyllis Basilone as he left home for the Army. She describes his getting on the train at Raritan for Newark and then traveling under the Hudson River into Manhattan, no date given. “Well, Sis, I'm on my way. I wonder if this is what I really want; everybody's advice is still ringing in my ears.” After all, the boy may not yet have turned eighteen.

11

When the Raritan Valley local pulled into its last stop one January morning in 2008, the three local men were waiting for me out in the cold in a red Lincoln truck because the station's waiting room was locked. We'd arranged for me to meet with some people in New Jersey who could tell me about John Basilone, his home and family, his roots. The men were John Pacifico, a Roman Catholic deacon for twenty-five years at St. Ann's Church on Anderson Street; Herb Patullo, who was driving the truck and who owns a historic piece of high ground in the nearby Watchung Mountains on which Washington and the Continental Army once encamped in a blocking position to mask Philadelphia from the British; and Peter Vitelli, a large, talkative man who used to be in sales and marketing in Manhattan and recalls that at age six at St. Joseph's parochial school in Raritan, he once shook Basilone's hand when the nuns trooped the returning hero around to the classrooms to greet the children in 1943.

Other books

The Wolf Who Loved Her by Kasey Moone

So Damn Beautiful (A New Adult Romance) by L.J. Kennedy

Champagne & Chaps by Cheyenne McCray

Zombie CSU by Jonathan Maberry

Smoked Out (Digger) by Warren Murphy

Disappearing Home by Deborah Morgan

Lucky Breaks by Patron, Susan

Song of the Fireflies by J. A. Redmerski

A Tapless Shoulder by Mark McCann

Escapology by Ren Warom