Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia (50 page)

Read Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia Online

Authors: Michael Korda

This daring and ambitious plan was thwarted at the last minute when one of the Indian machine gunners, slipping on the steep path down to the bridge, dropped his rifle. The Turkish sentry opened fire in return, blindly, in the dark; the Turkish guards came rushing out of their tent and opened fire; and the terrified “explosive-porters” dropped their sacks, which fell down the steep gorge toward the river, where it would obviously be impossible to retrieve them.

The retreat from the bridge was grim—every village on the way opened fire as Lawrence and his party passed it in the night, this being the standard practice when strangers were about. Also, the Serahin, angered by something Lawrence had said about their cowardice in dropping the explosives, paused to attack a group of peasants returning home late from the market at Deraa, stripping them of everything, including their clothes, and setting off from all sides outraged screams and volleys of rifle fire.

However sick at heart Lawrence might be at his failure, his Arabs were determined to come home with something in the way of loot; and since there was still one sack of explosive left, they wanted to blow up a train. Lawrence seems to have felt that this was unwise. For one thing, he had decided to send the machine gunners back to Azrak accompanied by Wood. (He hoped that Wood could enforce peace between the Indians and the Arabs, who hated each other even though both groups were Muslims.) Also, the party had run through its rations, having expected to dash back to Azrak once the bridge was blown, and so was not prepared for the day or two it might take to find a suitable place on the railway line and wait for a train. Still, Lawrence himself had no wish to return to Azrak without having accomplished anything.

He selected a stone culvert, in which he carefully concealed his bag of explosive, though he was hampered by the fact that he had only sixty yards of insulated cable with him—it was in short supply in Egypt—andwould be uncomfortably close to the explosion when it occurred. Before the exploder could be attached, a train of freight cars went by, and Lawrence huddled, “wet and dismal,” unable to blow them up. It rained hard, soaking the Arabs, but also discouraging the Turkish railway patrols from looking too hard at the ground as they went by, within a few yards of where Lawrence was hiding behind a tiny bush. The next to arrive was a troop train, and as it went by he pushed down the handle of the exploder, but nothing happened. As the carriages clanked by—three coaches for officers and eighteen open wagons and boxcars for the troops—he realized that he was now sitting in full view only fifty yards away from the train. Officers came out onto the little platforms at either end of their carriage, “pointing and staring.” Lawrence feigned simplicity and waved at them, aware that he made an unlikely figure of a shepherd in his white robes, with twisted gold and crimson

agal

wound around his headdress. Fortunately, he was able to conceal the wires and get away when the train drew to a stop and some of the officers got out to investigate—he “ran like a rabbit uphill into safety,” and he and his Arabs spent a cold, hungry, wet, sleepless night in a shallow valley beyond the railway. In the morning, Lawrence managed to get a small fire going by shaving slivers off a stick of blasting gelignite, while the Arabs killed one of the weakest camels and hacked it into pieces with their entrenching tools.

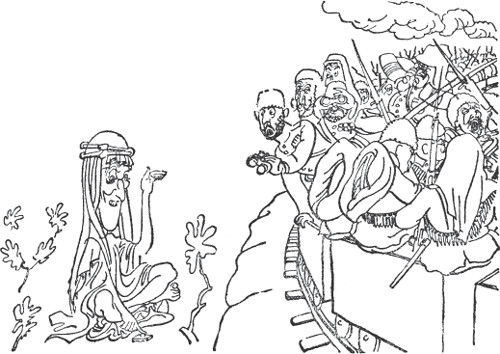

Lawrence prepares to blow up a train full of Turkish soldiers and their officers.

Before they could eat the meat, however, the approach of another train was signaled. Lawrence ran 600 yards, breathlessly, back to his tiny bush and pushed the handle of the exploder just as a train of twelve passenger carriages drawn by two locomotives appeared. This time it worked. He blew his mine just as the first locomotive passed over it, and sat motionless while huge pieces of black steel came hurtling through the air toward him. He felt blood dripping down his arm; the exploder between his knees had been crushed by a piece of iron; just “in front of [him] was the scalded and smoking upper half of the body of a man.” Lawrence had injured his right foot and in great pain limped toward the Arabs, caught in the cross fire as the Arabs and the surviving Turks opened fire on each other. He had suffered a broken toe and five bullet grazes, but was pleased, as the smoke cleared, to see that the explosion had destroyed the culvert and damaged both locomotives beyond repair. The first three carriages were badly crushed, and the rest derailed. One carriage was that of Mehmed Jemal Kuchuk Pasha,

*

the general commanding the Turkish Eighth Army Corps, whose personal chargers had been killed in the front wagon and whose car was at the end of the train. Lawrence “shot up” the general’s car, and also his imam, a priest who was thought to be “a notorious pro-Turk pimp” (an unusually savage comment for Lawrence); but there was not much more he could do against nearly 400 men with only forty Arabs, and the surviving Turks, knowing they were under the eye of a general, were beginning to deploy as they recovered from the shock. The Arabs were able only to loot sixty or seventy rifles, some medals, and assorted luggage scattered from the wreckage—enough, however, for them to feel that it was an honorable episode.

Lawrence made an effort to gather up those wounded who could be saved, including one Arab who had received a bullet in the face, knocking out four teeth and “gashing his tongue deeply,” but who still managed to get back on his camel and ride away. Someone had been farsighted enough to lash the bloody haunch of the slaughtered camel to his saddle, so once they were deeper in the desert, they halted and ate their first meal in three days, then rode back to Azrak, “boasting, God forgive us, that we were victorious.”

For Lawrence, this was a humiliating episode. Derailing a general’s train was not the kind of feat he wanted to bring Allenby. He guessed that the constant rain, turning everything to mud, would slow down the British advance in Palestine, and now regretted that he had been hesitant about sparking an Arab rising in Syria and had chosen to go for the Yarmuk bridge instead.

Lawrence took over the old fortress at Azrak, and made it his winter headquarters, so as to reach out toward Syria. Despite the icy cold, rainy weather, which rendered travel difficult, visitors poured in from the north to pledge their homage to Feisal, which Sharif Ali ibn el Hussein was happy to receive on his behalf; but Lawrence was not at his best in enforced idleness, or with the endless obligatory politeness of Arab greetings, or with the memory of his failure at the Yarmuk bridge tormenting him. From the small red-leather notebook in which he wrote down fragments of poetry that caught his attention, he searched for consolation and reread Arthur Hugh Clough’s “Say Not the Struggle Naught Availeth”:

And not through eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

But it was irony he found, not consolation. Westward, in Palestine, the weather was the same as at Azrak; and since Lawrence could safely leavethe greeting of Syrian dignitaries to Ali, he set out to do a reconnaissance with the swaggering, glamorous Talal el Hareidhin, sheikh of Tafas, “an outlaw with a price upon his head,” who was familiar with the approaches to Deraa. For Deraa still fascinated Lawrence as an objective; if he could take the town and hold it, if only for a few days, he could cut off all railway traffic to Palestine, and as well give the Arab cause a victory that would not only satisfy Allenby, but go a long way toward convincing the British, and perhaps even the French, to accept an independent Arab state in Syria. His mind buzzed with plans to take Deraa, but he needed to see for himself the lay of the land, and above all the strength or weakness of the Turkish garrison there.

He decided to go there himself.

Probably no incident in Lawrence’s life looms larger than Deraa, or is more controversial. His decision to go there is hotly debated, and often criticized, but Lawrence had always been as reckless when it came to his own safety as he was careful of the life of others—indeed he made a point of courting danger—and it is also hard to calculate the degree to which his failure to destroy the bridge at Tell el Shehab weighed on him. His admiration for Allenby was enormous, uncomplicated, and sincere—Allenby’s huge, commanding presence made him seem to Lawrence like a natural feature, something immovable and irresistible, a mountain perhaps; and having failed to keep what he regarded as a promise to Allenby, he felt obligated to provide an acceptable substitute. Capturing Deraa would be as good as destroying the bridge at Tell el Shehab, or even better.

Talal could not have accompanied Lawrence into Deraa, even had he wanted to—he was a dashingly dressed and flamboyant figure, with “a trimmed beard and long pointed moustaches … his dark eyes made rounder and larger and darker by their thick rims of antimony,” who had “killed some twenty-three Turks with his own hand,” and was wanted by the Turks almost as much as Lawrence was. Talal appointed Mijbil, an elderly, ragged peasant, to guide Lawrence through the town, and Lawrence disguised himself by leaving behind his white robes and gold dagger, and wearing instead a stained, muddy robe and an old jacket.

It occurred to Lawrence that Abd el Kader would long since have given the Turks an accurate description of him, but this does not appear to have caused him any concern, though it should have. His intention was simply to walk through the town with Mijbil and see whether it would be better to rush the railway junction first, or to cut the town off by destroying the three railways lines that entered it. They made “a lame and draggled pair” as they sauntered barefoot in the mud toward Deraa, following the Palestine railway line past the fenced-in “aerodrome,” where there was a Turkish troop encampment, and a few hangars containing German Albatros aircraft. Since Lawrence was looking for a way to attack the city from the desert, this approach made sense—the railway bank and the fence were impediments worth noting—but it must also be said that he could hardly have picked anyplace in Deraa more likely to be guarded with some care than a military airfield.

In any case, after a brief altercation with a Syrian soldier who wanted to desert, Lawrence was grabbed roughly by a Turkish sergeant, who said, “The Bey wants you,” and dragged him through the fence into a compound, where a “fleshy” Turkish officer sat and asked him his name. “Ahmed ibn Bagr,” Lawrence replied, explaining that he was Circassian. “A deserter?” the officer asked. Lawrence explained that Circassians had no military service. “He then turned around and stared at me curiously, and said very slowly, ‘You are a liar. Keep him, Hassan Chowish, til the Bey sends for him.'”

Lawrence was led to the guardroom, told to wash himself, and made to wait. With his fair complexion, blond hair, and blue eyes he might, of course, have been a Circassian, and it was no doubt his boyish appearance and size that had attracted unwelcome attention. He himself had always admitted that he could not “pass as an Arab,” but now his life depended on whether he could pass as a Circassian. He was told that he might be released tomorrow, “if [he] fulfilled all the Bey’s pleasure this evening,” which can have left him in little doubt about what was in store for him. Lawrence had the impression that the bey was Hajim (actually Hacim Bey), the governor of Deraa, but he could have been mistaken.

“The garrison commander at Deraa was Bimbashi [Major] Ismail Bey and the militia commander Ali Riza Bey.” It seems unlikely that the governor of Deraa would have lodged in a military compound next to the airfield and the railway yard; and in Turkish the title “bey” had long since lost its original significance of “chieftain” and become a widespread honorific roughly equivalent to the use of “esquire” instead of Mr. in Britain: i.e., a member of the educated professional, officer, or senior civil servant class, a step above “effendi” and a couple of steps below “pasha.”

That evening Lawrence was taken upstairs to the bedroom of the bey, “a bulky man sitting on his bed in a night-gown trembling and sweating as though with fever.” The bey looked him over, and then dragged him down onto the bed, where Lawrence struggled against him as if they were wrestling. The bey ordered Lawrence to undress, and when he refused to, called in the sentry who was posted outside the door, ordered the sentry to strip Lawrence naked, and began “to paw” at him. Lawrence then kneed the bey in the groin. The bey collapsed in pain, then, calling for the other three men of the guard, had him held naked, spat in Lawrence’s face, and slapped his face with one of his slippers, promising “that he would make me ask pardon.” He bit Lawrence’s neck, then kissed him, then drew one of the men’s bayonets and plunged it into Lawrence’s side, above a rib, twisting it to give more pain. Lawrence lost his self-control enough to swear at him, and the bey then calmed himself, and said, “You must understand that I know about you, and it will be much easier if you do as I wish.”