Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries (29 page)

Read Hidden History: Lost Civilizations, Secret Knowledge, and Ancient Mysteries Online

Authors: Brian Haughton

Tags: #Fringe Science, #Gnostic Dementia, #U.S.A., #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #History

Alternatively, the carving may

have been created for ritual/religious

purposes. Some see the horse as representing the Celtic horse goddess

Epona, who was worshipped as a protector of horses, and also had associations with fertility. However, the cult

of Epona was imported from Gaul (France) probably in the first century

A.D., which is when we find the first

depictions of the horse goddess. This

date is at least six centuries after the

Uffington Horse was carved. Nevertheless, the horse was of great ritual and

economic importance during the

Bronze and Iron Ages, as attested by

its depictions on jewelry, coins, and

other metal objects. Perhaps the carving represents a native British horsegoddess, such as Rhiannon, described

in later Welsh mythology as a beautiful woman dressed in gold and riding

a white horse. Others see the White

Horse as connected with the worship

of Belinos or Belinus, "the shining

one," a Celtic Sun God often associated

with horses. Bronze and Iron Age sun

chariots (mythological representations

of the sun in a chariot), were shown as

being pulled by horses, as can be seen

from the 14th century B.c. example from

Trundholm in Denmark. If, as is now

believed, Celtic culture had reached

Britain by the very end of the Bronze

Age, then the White Horse could still

be interpreted as a Celtic horsegoddess symbol.

There are some who believe that

the great carving does not represent

a horse at all, but rather a dragon. A

legend connected with Dragon Hill, a

low natural flat-topped mound situated in the valley below the White

Horse, suggests that the horse depicts

the mythical dragon slain by St.

George on that hill. The blood of the

dying dragon was supposed to have

been spilled on Dragon Hill, leaving a

bare, white chalk scar where, to this

day, no grass will grow. Perhaps the

St. George connection with the White

Horse is a confused memory of some

strange prehistoric ritual performed

on Dragon Hill by its creators, perhaps

as long as 3,000 years ago. Up until the

late 19th century the White horse was

scoured every year, as part of a two

day Midsummer country fair, which

also included traditional games and

merrymaking. Nowadays, the accompanying festival is gone, and the task

of maintaining the horse is undertaken

by English Heritage, the organization

responsible for the site. The last scouring took place on June 24, 2000.

A further example of an ancient

horse is the Red Horse of Tysoe, which

once existed on the Edgehill scarp,

above the village of Lower Tysoe in

Warwickshire. Unfortunately, this

strange creature, actually multiple

horses carved in the same area, was

ploughed over and disappeared in

1800. The history and design of the Red

Horse is obscure. It was first mentioned in 1607 in Britanica, written by

the English antiquarian and historian

William Camden. In the 17th century,

the English traveler Celia Feinnes

described the horse when travelling

through the area, writing, "It's called

the Vale of Eshum or `of the Red Horse'

from a red horse cut on some of the

hills about it, and the Earth all looking red the horse lookes so as that of

the White Horse Vale." Since the

1960s, investigation into the Red Horse

using ground survey, aerial photographs, and local archives research

has managed to locate as many as six

separate horses. At present, the consensus of opinion is that the original

Red Horse of Tysoe, or Great Horse,

was cut in Anglo-Saxon times around

A.D. 600, possibly as a representation

of the Saxon war god Tiw or Tiu, from

whom the village of Tysoe allegedly takes its name, and from where we get

our word Tuesday (Tiw's day).

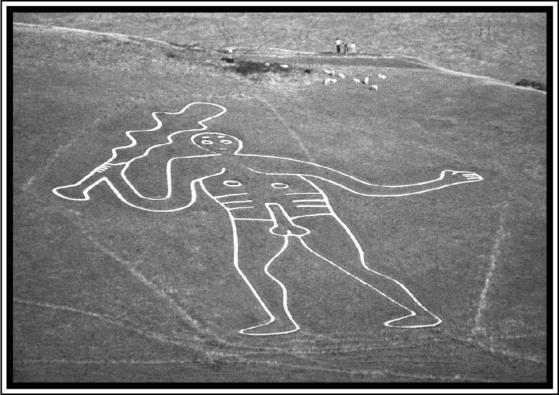

Photograph courtesy of SacredSites.com.

The Cerne Abbas giant.

Almost as well-known as the

Uffington White Horse is the 180 foot

tall Cerne Abbas Giant, an ithyphallic

figure cut into the hillside to the northeast of the village of Cerne Abbas, and

to the north of Dorchester, Dorset.

The carving is of a giant, roundheaded, naked man with a distinct

erect penis and testicles, wielding a

huge knobbed club in his right hand.

As with the White Horse at Uffington,

it is not possible to fully appreciate the

figure from the ground; only from the

air can the giant be seen in all his

glory. Above the giants's head lies a

rectangular earthwork enclosure,

called the Trendle, or frying pan,

thought possibly to be an Iron Age

temple site, which some researchers

believe is connected with the huge

chalk figure below it. The favorite interpretations of the Cerne Giant is

that he either represents a prehistoric

fertility god or a Roman carving of

Hercules wielding his giant club. Up

until 1635 there were Mayday fertility celebrations on the hill, with the

maypole being erected inside the

Trendle, around which locals would

dance.

However, unlike the Uffington

White Horse, the earliest surviving

reference to the Cerne Giant dates

only as far back as 1694, when it is

mentioned in the village church's accounts. It was subsequently surveyed

in 1764, and the results published in

the Gentleman's Magazine that year.

Writing in 1774, John Hutchins in his

History and Antiquities of the County

of Dorset, states that the figure was

supposed to have been cut in the

middle of the 17th century as a joke,

though he also mentions that some of

the older residents of the village had

in the past claimed it had been there

"beyond the antiquity of man." However, the weight of evidence does tend

to support a recent origin for the giant. One theory is that although the

giant is indeed a depiction of Hercules,

it actually represents a caracature of Oliver Cromwell, who was sometimes

referred to as the English Hercules,

and was cut on the instructions of local landowner Denzil Holles some time

in the 1640s. Another factor that supports this date is that medieval records

always refer to the hill on which the

giant is carved as Trendle Hill, rather

than the modern Giant Hill, making no

mention of the huge carving. This

would indicate that the giant has only

existed for about 400 years. Another

interpretation, however, would be that

for some reason, perhaps its overt

sexuality, writers chose to ignore the

Cerne Giant. Perhaps it had even become overgrown and forgotten.

New research into another chalk

giant, however, may add support to the

more recent date for the Cerne Abbas

figure. Carved into the steep slopes of

Windover Hill, Sussex, the 226-feethigh Long Man of Wilmington is the

tallest hill figure in England, and was,

until recently, believed to be of prehistoric origin. But the latest archaeological study at the site (using the

same OSL dating technique as on the

Uffington White Horse) produced evidence that the earlier theories are

wrong and that the figure had been

carved as recently as A.D. 1545. Although the new dating of the

Wilmington Giant to the medieval period does throw considerable doubt on

the prehistoric credentials of the

Cerne Abbas Giant, until OSL dating

is carried out on the carving, the giant

English Hercules will remain an

enigma.

The reasons for the creation of

these hill figures are probably as varied as the figures represented. New

archaeological and geological evidence

is increasingly indicating a medieval

date for the giant naked figures, which

some historians have argued were

products of an age of civil war and extreme political turmoil in England,

when satire was sometimes the only

weapon. Compared to the huge stone

permanence of structures, such as the

Avebury Monuments and Stonehenge,

hill figures are much more transitory;

10 or 20 years without scouring, and

the carving could be lost forever. The

fact that the figures could disappear

so easily, along with their associated

rituals and meaning, indicates that

they were never intended to be anything more than temporary gestures,

which have only survived either by

accident, or, in the case of the

Uffington White Horse Abbey, by the

continued existence of extraordinarily tenacious local tradition. But this

does not lesson their importance.

These giant carvings are a fascinating

glimpse into the lives and minds of

their creators and how they viewed

the landscape in which they lived.

The original artifact inside the supposed geode.

For some people, out of place artifacts (objects found in contexts that are

out of sync with the accepted chronology of human history) seriously question what we think we know about the

world and its history. Some argue that

these discoveries offer persuasive evidence that in remote antiquity, mankind was significantly more advanced

than we could ever imagine. They insist that at various times in prehistory

we have reached a high level of civilization, only for it to be subsequently

destroyed, without a trace, by natural

or man-made catastrophes. The evidence for such hypothetical ancient

civilizations consists mainly of what

appear to be fossilized human footprints, such as those discovered in the

1880s at the summit of Big Hill in the

Cumberland Mountains in Jackson

County, Kentucky (The American Antiquarian, January 1885), and apparently man-made objects enclosed in

pieces of coal or rock. The Coso Artifact is such an example.

On February 13, 1961, Wallace

Lane, Virginia Maxey, and Mike

Mikesell (co-owners of the LM&V

Rockhounds Gem and Gift Shop in

Olancha, southern California) were out in the Coso Mountains looking for

interesting mineral specimens, particularly geodes (hollow, usually spheroid rocks with crystals lining the inside

wall, cmmonly around 500,000 years

old) for their collection. At lunchtime,

after they had been collecting rocks,

close to the top of a 4,265 foot peak,

overlooking the dry bed of Owens Lake,

they put their specimens in the rock

sack and headed home.

The next day, while attempting to

cut through one of the finds that appeared to be a geode, Mikesell severely

damaged a practically new diamond

saw. Finally, when the nodule was

opened, he found a thick circular section of white porcelain material, in the

center of which was a 2 millimeter rod

of bright metal. This metal proved to

be magnetic. The porcelain cylinder

was itself enclosed by a hexagonal

sheath of decomposing copper and another unidentifiable substance. The

discoverers noticed other strange

qualities about the stone. Its outer

layer was encrusted with bits of fossil

shell, hardened clay, and pebbles, and

more surprisingly, two nonmagnetic

metal objects which looked similar to

a nail and a washer. Puzzled by the

find, the group began showing it to

friends and associates, though little

record remains now of original examinations of the object. One of the discoverers, Virginia Maxey, said that a

geologist who examined the object

gave its age, based on the fossils encrusted in its shell, as at least 500,000

years old. However, this unnamed geologist has never been traced and the

conclusion was never published. But if

these conclusions could be supported,

then the implications are clear. If the

Coso Artifact is a genuine example of