High Price (10 page)

Authors: Carl Hart

Marcia Billings, on the other hand, was a good girl—but not

too

good. She was the girl I wanted, with a perfect hourglass figure. She was built and fine. Marcia was about five foot two and weighed around 120 pounds. I first saw her in a McDonald’s, after a basketball game when I was fourteen, a few weeks after I’d been with Kim. I awkwardly propositioned her, but she shot me down. All that took was a look and maybe a few harsh words, something like “Keep stepping” or “Nigga, please.”

I was shocked; because I was skilled at reading girls’ signals, that kind of thing almost never happened to me. But a few months later, my cousin James was dating one of her friends and he reintroduced us. She didn’t remember the earlier incident. Now she was quite happy to meet the young DJ who was part of a crew that had begun tearing up the gyms and skating rinks of South Florida. She became my main girlfriend for most of high school. I gave Marcia my class ring and she was the one I took to the senior prom. As much as I was able to at the time, I loved her.

The more time we spent together, the more her warmth and spirit nurtured me. In fact, I was soon spending most of my nights at her house. We watched the Brooke Shields movie

Endless Love

together and I’m sure we saw ourselves in the dangerous passion shared by the young couple in the movie. I knew that she had my back and she occupied much of my time.

My mother was suspicious and even resentful of Marcia at first. She even tried to split us up by calling Marcia a ho and attempting to make me question Marcia’s loyalty to me. But when MH finally realized that this was a battle she’d never win—and that she could find out where I was by calling Marcia—she turned around and accepted our relationship. Still, Marcia was never the only girl I was seeing. Soon, in an ironic reversal, she would sometimes call MH to try to locate me when I was on the prowl.

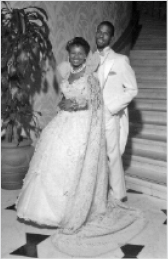

Marcia and me at my senior prom in May 1984.

In our world, the girls knew the score and they, too, competed openly to win the finest man. It was understood implicitly that the popular guys had other women: it certainly wasn’t blindly accepted or preferred and it was often a source of friction, but nonmonogamy was seen as an undeniable reality. Many girls worked it as well as the boys did. This was something that also went unquestioned.

Naomi was another girl I saw in high school—but in this case, one who nearly got me in serious trouble. Light-skinned with a fun-loving but no-nonsense personality, Naomi went by the alias Sweet Red. She was twenty-one but looked and acted much younger. I started seeing her when I was sixteen. One night, we were in the master bedroom of my cousin Betty’s house, which she shared with her husband and two children. Betty and Ernest were in the process of getting divorced. Because their conflict over disposal of the marital property meant that no one was home most of the time, my cousin James and I often took girls there. We even had the keys.

However, when Ernest arrived unexpectedly and found Naomi and me in his bed, I had to very quickly demonstrate that Naomi was not his soon-to-be ex-wife and I was not any kind of rival for her attention. He was seeing red, believing that Betty had dared to bring another man into his own home. Fortunately, I was able to calm him down before he pulled his gun, but I was lucky not to be a victim of mistaken identity in my pursuit of Naomi.

Those are just a few of the girls who stick out most in my mind. There were many others, some one-night stands, some longer-term friend-girls. As I mentioned earlier, the mother of my son Tobias was a girl whom I’d gotten with only once.

In terms of sex, then, my adolescence was not one of deprivation. I certainly don’t say this to brag. Sexual fidelity and infidelity are a matter of conflict in every society. Here I’d just like to make clear that my relationships with women sustained me emotionally and buoyed me up when I wasn’t getting the nurture and encouragement I needed at home.

I will also note parenthetically that my experience shows that you can become a scientist without having been socially inept as a kid. Unlike many of my lab mates, I did not sit at home, fantasizing about unapproachable girls in tight jeans who were oblivious to my existence. I wasn’t the science geek alone with my books or the dork who couldn’t even talk to a lady. I didn’t spend hours with pornography. Indeed, I was so sexually active that some media “experts” might even have called me a “sex addict.”

But that wasn’t quite what was going on. Instead, my experience illustrates the problems with reducing complex human behavior to simplistic terms like

addiction

and with trying to blame specific brain chemicals for people’s actions. Doing so fails to consider the context under which the behavior occurs. It also places an unwarranted emphasis on coming up with a brain explanation, when carefully understanding the behavior and its context could be much more useful in explaining and altering it.

My behavior with girls reflected not just biology but context and experience. It was not just pure sex drive (though that was certainly there) but sex drive modulated by my social context, including family expectations and neighborhood norms. It was about my desire to be cool, the local concepts of cool and how I interpreted them. It was about the rules I internalized—such as the idea that masturbation wasn’t manly—as well as the ones that I didn’t. It was frankly, also, about a need for comfort and contact. While science must reduce complexity in order to conduct studies, the interpretation of that data cannot simply then be extrapolated back without recognizing these and other relevant caveats.

As a neuroscientist, however, I didn’t recognize this at first and I think many of my colleagues still have difficulty doing so. When I started my career, there was great excitement around a neurotransmitter called dopamine, which was believed to explain why people got addicted to drugs. It was even seen as driving behaviors like the propensity for sexual variety. Indeed, some people seemed to believe it could account for all forms of desire and pleasure. And at first, I, too, thought dopamine could answer these kinds of questions. Recognizing why it cannot be the sole answer is an important part of developing a more sophisticated and productive way of understanding how drugs affect behavior and consequently, how to develop better ways to treat addiction.

T

he green blips on the oscilloscope were coming fast and furious.

Poppoppoppoppop

was the sound accompanying the images, which were generated by the firing of neurons in a region of the rat brain called the nucleus accumbens. I was monitoring the experiment, studying the effects of morphine or nicotine on these brain cells. Previously, I’d operated on the rat, delicately implanting electrodes into the accumbens to measure the way the neurons there would react to the drugs. Although we couldn’t tell directly using this technique, we believed we were studying cells that used dopamine as their neurotransmitter, since these were the most common type of cell in that brain area.

It was 1990. I was an eager young college student, working at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. President George H. W. Bush had labeled that year as the start of the decade of the brain. Dopamine was at the center of addiction research. Researchers like Roy Wise and George Koob had propounded the theory that all psychoactive drugs that people enjoy—everything from alcohol to cocaine to heroin—increased the activity of dopamine neurons in this region.

1

This was believed to cause intense pleasure, which in turn produced desire for more.

And, in the case of drug use, that desire was said to be so overwhelming as to “hijack” the brain’s “pleasure center,” a major part of which is known as the nucleus accumbens. According to the theory, this center was supposed to be activated by “natural” rewards like sex or food, things that would help an animal compete in the evolutionary race for survival. But drugs can increase the activity of dopamine neurons even more than these ordinary pleasures. As a result, with their brains taken hostage by these unnatural experiences, addicts were seen as inevitably doomed to lose control over their behavior. The need to chase more dopamine would leave them begging, borrowing, stealing, dealing, even killing for more drugs as a result. Dopamine was said to make crack cocaine irresistible and crack addicts’ behavior uncontrollable.

This “dopamine hypothesis of addiction” had its beginnings in an accidental observation by James Olds and Peter Milner at McGill University, in Montreal, way back in the early 1950s. They had heard in a lecture that a brain network then known as the reticular activating system (RAS) would motivate rats to learn mazes better if it was stimulated electrically. Increasing the activity of the cells in this network appeared to make rats more alert and more successful at remembering the maze. Eager to study this for themselves, Olds and Milner placed electrodes into rat brains (similarly to the way I would later do, though I was measuring activity rather than adding electricity to stimulate the brains of my rats). They tried to place the electrodes so they could stimulate the RAS.

Once these electrodes were implanted and the rats had recovered from the surgery, the researchers placed the animals, one at a time, in a box. Each corner was labeled: A, B, C, D. Whenever the rat wandered over to corner A, the scientists hit a button to electrically stimulate its brain. Most of the rats just wandered aimlessly. But one particular rat would repeatedly return to corner A, especially during the stimulation, as though the stimulation had made this corner very attractive.

Olds and Milner began to wonder if they’d misplaced the electrode in this rat. They decided to examine its brain closely to see where the probe had landed. When the researchers dissected its brain, they found that they had indeed put the electrode in the wrong spot, accidentally landing in a region known as the medial forebrain bundle (MFB).

Initially, the researchers thought they’d discovered that the MFB made rats curious or interested. And that was probably part of what was going on. But in order to try to figure out exactly what was happening, they next deliberately implanted electrodes in this region in other rats. Instead of stimulating their brains manually, however, Olds and Milner put levers in the rats’ cages to allow them to stimulate themselves. And, once the scientists let the rodents start pressing the lever, some began hitting it up to seven hundred times an hour.

2

Though these findings have been exaggerated—in both the scientific literature and popular press—to make it look like no rat could ever “just say no” to this type of self-stimulation, many rats actually didn’t learn to self-stimulate and couldn’t be trained to do it. As with drug addiction, this is not a phenomenon that can be understood in isolation from the rest of the environment, even in rats. And as with drug addiction, the truly compulsive behavior was seen only under specific conditions.

Nonetheless, Olds and Milner soon realized that they might be on to something much bigger than a way to enhance learning. They’d discovered some kind of joy spot—in fact, the area soon became known as the brain’s “reward” or “pleasure” center. Later, in the 1960s, other researchers would discover that the most abundant neurotransmitter in this region was dopamine and that the MFB carried signals between regions we now think are involved in pleasure and desire, such as the nucleus accumbens.

The rats’ behavior with the lever appeared to be a model for reward that could be used to study addiction. Now all that was left to do, it seemed, was to figure out how different drugs interact with dopamine and then discover ways to block this. Addiction might be cured, once and for all.

Over time, however, as you’ve probably guessed by now, it’s a lot more complicated than we initially thought. When dopamine’s prominent role in reward was proposed, there were only about six known neurotransmitters: dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, glutamate, and GABA. Now there are more than a hundred. Furthermore, we now know that there are specific receptors—or specialized structures that recognize and respond to a particular neurotransmitter—for each neurotransmitter, and most neurotransmitters have more than one type of receptor. For example, dopamine has at least five receptor subtypes—D1–D5. We also now know that hormones like oxytocin and testosterone can act as neurotransmitters.

But despite these ever-intensifying complexities, our theory about dopamine’s role in reward has not been appreciably revised since it was originally proposed. And, as you will see later, a growing body of evidence casts doubt on this simplistic view of reward.

Nonetheless, when I started studying addiction, I was a true believer in the dopamine hypothesis. I thought that dopamine probably drove sexual and gustatory excess, that it made crack cocaine addicts crazed with cravings. Many of the researchers I worked with were convinced; my heroes were people like Olds and Milner and Wise and Koob, who had made key discoveries through animal research on brain mechanisms involved in reward. I thought that if we could just understand how drugs of abuse interacted with this neurotransmitter, we’d easily develop better treatments—perhaps even a cure—for addiction. The answers were in this one chemical in this key circuitry of the brain.