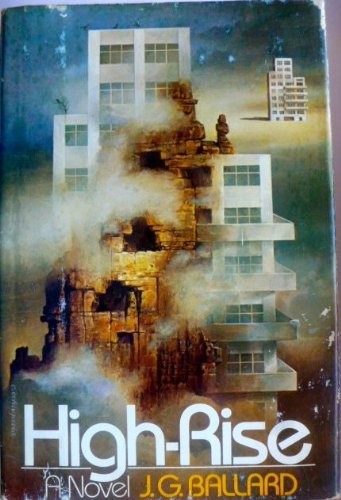

High-Rise

Annotation

J.G. Ballard's 1975 novel "High Rise" contains all of the qualities we have come to expect from this author: alarming psychological insights, a study of the profoundly disturbing connections between technology and the human condition, and an intriguing plot masterfully executed. Ballard, who wrote the tremendously troubling "Crash," really knows how to dig deep into our troubling times in order to expose our tentative grasp of modernity. Some compare this book to William Golding's "Lord of the Flies," and there are definite characteristics the two novels share. I would argue, however, that "High Rise" is more eloquent and more relevant than Golding's book. Unfortunately, this Ballard novel is out of print. Try and locate a copy at your local library because the payoff is well worth the effort.

"High Rise" centers around four major characters: Dr. Robert Laing, an instructor at a local medical school, Richard Wilder, a television documentary producer, Anthony Royal, an architect, and the high rise building all three live in with 2,000 other people. Throughout the story, Ballard switches back and forth between these three people, recording their thoughts and actions as they live their lives in the new high-rise apartment building. Ballard made sure to pick three separate people living on different floors of the forty floor building: Laing lives on the twenty fifth floor, Wilder lives on the second floor, and Royal lives in a penthouse on the fortieth floor (befitting his status as the designer of the building). Where you live in this structure will soon take on an importance beyond life itself.

At the beginning of the story, most of the people living in the building get along quite well. There are the usual nitpicky problems one would expect when 2,000 people are jammed together, but overall people move freely from the top to the bottom floors. A person living on the bottom floors can easily go to the observation deck on the top of the building to enjoy the view, or shop at the two banks of stores on the tenth and thirty-fifth floors. Children swim and play in the pools and playgrounds throughout the high rise without any interference. Despite the fact that well to do people live in the building, with celebrities and executives on the top floors, middle-class people on the middle floors, and airline pilots and the like on the bottom ten floors, everyone gets along reasonably well-at first.

Then things change. The gossip level increases among the residents, and parties held on different floors start to exclude people from other areas. In quick succession, objects start to land on balconies, dropped by residents on higher levels. Equipment failures, such as electrical outages, lead to mild assaults between residents. Cars parked close to the building are vandalized, and a jeweler living on the fortieth floor does a swan dive out of the window. Every incident leads to further acts of violence and increasing chaos in the lives of those in the building. People begin to take a greater interest in what's going on where they live than in outside activities and jobs. As the violence escalates, elevators and lobbies on each floor turn into armed camps as the residents attempt to block any encroachments on their territory. What starts out as a book about living in a technological marvel quickly morphs into a study of how technology can cause human beings to regress back into primitivism. Moreover, Ballard tries to draw a correlation between the technology of the building and this descent into a Stone Age mentality. He shows in detail how the residents of the apartments sink back into the morass, passing through a classical Marxist structure of bourgeoisie-proletariat, moving on to a clan/tribal system, to a system of stark individuality. In short, Ballard tries to equate our striving towards individuality through technology with how we started out in our evolution as hunter-gatherers, as individuals seeking individual gains. The promise that technology will liberate the individual is not the highest form of evolution, argues Ballard, but is actually a return to the lowest forms of human expression.

Within a few pages of the story, I thought this might turn out to be very similar to a Bentley Little book. Little, nominally a horror writer but often a social satirist, often takes a situation like this and shows how people collapse under the pressures of modern life. My belief was not born out, however, not because Ballard doesn't take certain situations over the top but because he imbues his work with a significant philosophical subtext that Little would never write about. Bentley Little is all about focusing on the over the top, outrageous incidents of humanity's decline, whereas Ballard is more interested in serving as a preacher on anti-humanistic technology, thundering out a jeremiad concerning where we might go if we do not take the time to think very carefully about the society we wish to create.

"High Rise" is a dark, forbidding tale of woe that is sure to get a reaction from anyone who reads it. There seem to be few out there who can deliver such devastating blows to our love of technology as Ballard does in his works. This author is often referred to as a science fiction writer, but "High Rise" works just as well on a horror level. So does "Crash," when I think about it, although the cold, detached prose of that book is not present in "High Rise." Whatever genre Ballard falls into, this book delivers on every level.

- J. G. Ballard

- 1

- 2. Party Time

- 3. Death of a Resident

- 4. Up!

- 5. The Vertical City

- 6. Danger in the Streets of the Sky

- 7. Preparations for Departure

- 8. The Predatory Birds

- 9. lnto the Drop Zone

- 10. The Drained Lake

- 11. Punitive Expeditions

- 12. Towards the Summit

- 13. Body Markings

- 14. Final Triumph

- 15. The Evening's Entertainment

- 16. A Happy Arrangement

- 17. The Lakeside Pavilion

- 18. The Blood Garden

- 19. Night Games

- 1

High Rise

1

Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months. Now that everything had returned to normal, he was surprised that there had been no obvious beginning, no point beyond which their lives had moved into a clearly more sinister dimension. With its forty floors and thousand apartments, its supermarket and swimming-pools, bank and junior school-all in effect abandoned in the sky-the high-rise offered more than enough opportunities for violence and confrontation. Certainly his own studio apartment on the 25th floor was the last place Laing would have chosen as an early skirmish-ground. This over-priced cell, slotted almost at random into the cliff face of the apartment building, he had bought after his divorce specifically for its peace, quiet and anonymity. Curiously enough, despite all Laing's efforts to detach himself from his two thousand neighbours and the regime of trivial disputes and irritations that provided their only corporate life, it was here if anywhere that the first significant event had taken place-on this balcony where he now squatted beside a fire of telephone directories, eating the roast hind-quarter of the alsatian before setting off to his lecture at the medical school.

While preparing breakfast soon after eleven o'clock one Saturday morning three months earlier, Dr Laing was startled by an explosion on the balcony outside his living-room. A bottle of sparkling wine had fallen from a floor fifty feet above, ricocheted off an awning as it hurtled downwards, and burst across the tiled balcony floor.

The living-room carpet was speckled with foam and broken glass. Laing stood in his bare feet among the sharp fragments, watching the agitated wine seethe across the cracked tiles. High above him, on the 31st floor, a party was in progress. He could hear the sounds of deliberately over-animated chatter, the aggressive blare of a record-player. Presumably the bottle had been knocked over the rail by a boisterous guest. Needless to say, no one at the party was in the least concerned about the ultimate destination of this missile-but as Laing had already discovered, people in high-rises tended not to care about tenants more than two floors below them.

Trying to identify the apartment, Laing stepped across the spreading pool of cold froth. Sitting there, he might easily have found himself with the longest hangover in the world. He leaned out over the rail and peered up at the face of the building, carefully counting the balconies. As usual, though, the dimensions of the forty-storey block made his head reel. Lowering his eyes to the tiled floor, he steadied himself against the door pillar. The immense volume of open space that separated the building from the neighbouring high-rise a quarter of a mile away unsettled his sense of balance. At times he felt that he was living in the gondola of a ferris wheel permanently suspended three hundred feet above the ground.

Nonetheless, Laing was still exhilarated by the high-rise, one of five identical units in the development project and the first to be completed and occupied. Together they were set in a mile-square area of abandoned dockland and warehousing along the north bank of the river. The five high-rises stood on the eastern perimeter of the project, looking out across an ornamental lake-at present an empty concrete basin surrounded by parking-lots and construction equipment. On the opposite shore stood the recently completed concert-hall, with Laing's medical school and the new television studios on either side. The massive scale of the glass and concrete architecture, and its striking situation on a bend of the river, sharply separated the development project from the run-down areas around it, decaying nineteenth-century terraced houses and empty factories already zoned for reclamation.

For all the proximity of the City two miles away to the west along the river, the office buildings of central London belonged to a different world, in time as well as space. Their glass curtain-walling and telecommunication aerials were obscured by the traffic smog, blurring Laing's memories of the past. Six months earlier, when he had sold the lease of his Chelsea house and moved to the security of the high-rise, he had travelled forward fifty years in time, away from crowded streets, traffic hold-ups, rush-hour journeys on the Underground to student supervisions in a shared office in the old teaching hospital.

Here, on the other hand, the dimensions of his life were space, light and the pleasures of a subtle kind of anonymity. The drive to the physiology department of the medical school took him five minutes, and apart from this single excursion Laing's life in the high-rise was as self-contained as the building itself. In effect, the apartment block was a small vertical city, its two thousand inhabitants boxed up into the sky. The tenants corporately owned the building, which they administered themselves through a resident manager and his staff.

For all its size, the high-rise contained an impressive range of services. The entire 10th floor was given over to a wide concourse, as large as an aircraft carrier's flight-deck, which contained a supermarket, bank and hairdressing salon, a swimming-pool and gymnasium, a well-stocked liquor store and a junior school for the few young children in the block. High above Laing, on the 35th floor, was a second, smaller swimming-pool, a sauna and a restaurant. Delighted by this glut of conveniences, Laing made less and less effort to leave the building. He unpacked his record collection and played himself into his new life, sitting on his balcony and gazing across the parking-lots and concrete plazas below him. Although the apartment was no higher than the 25th floor, he felt for the first time that he was looking down at the sky, rather than up at it. Each day the towers of central London seemed slightly more distant, the landscape of an abandoned planet receding slowly from his mind. By contrast with the calm and unencumbered geometry of the concert-hall and television studios below him, the ragged skyline of the city resembled the disturbed encephalograph of an unresolved mental crisis.

The apartment had been expensive, its studio living-room and single bedroom, kitchen and bathroom dovetailed into each other to minimize space and eliminate internal corridors. To his sister Alice Frobisher, who lived with her publisher husband in a larger apartment three floors below, Laing had remarked, "The architect must have spent his formative years in a space capsule-I'm surprised the walls don't curve..."

At first Laing found something alienating about the concrete landscape of the project-an architecture designed for war, on the unconscious level if no other. After all the tensions of his divorce, the last thing he wanted to look out on each morning was a row of concrete bunkers.

However, Alice soon convinced him of the intangible appeal of life in a luxury high-rise. Seven years older than Laing, she made a shrewd assessment of her brother's needs in the months after his divorce. She stressed the efficiency of the building's services, the total privacy. "You could be alone here, in an empty building-think of

that

, Robert." She added, illogically, "Besides, it's full of the kind of people you ought to meet."

that

, Robert." She added, illogically, "Besides, it's full of the kind of people you ought to meet."

Other books

Alpha Trio 3: A Special Taste by Ana Vela

Mind Games by Teri Terry

The Devil Is a Part-Timer!, Vol. 5 by Satoshi Wagahara

Element Wielder (The Void Wielder Trilogy Book 1) by Cesar Gonzalez

Close Encounters of the Third Kind by Steven Spielberg

London Wild by V. E. Shearman

The Price We Pay by Alora Kate

Wilderness Trail of Love (American Wilderness Series Romance Book 1) by Dorothy Wiley

Between the Waters (Symphony of Light) by Renea Mason

Ray & Me by Dan Gutman