High Steel: The Daring Men Who Built the World's Greatest Skyline

Read High Steel: The Daring Men Who Built the World's Greatest Skyline Online

Authors: Jim Rasenberger

Tags: #General, #United States, #Biography, #20th century, #Northeast, #Travel, #Technology & Engineering, #History, #New York, #Middle Atlantic, #Modern, #New York (N.Y.), #Construction, #Architecture, #Buildings, #Public; Commercial & Industrial, #Middle Atlantic (NJ; NY; PA), #New York (N.Y.) - Buildings; structures; etc, #Technical & Manufacturing Industries & Trades, #Building; Iron and steel, #Building; Iron and steel New York History, #Structural steel workers, #New York (N.Y.) Buildings; structures; etc, #Building; Iron and steel - New York - History, #Structural steel workers - United States, #Structural steel workers United States Biography

THE DARING MEN WHO BUILT THE WORLD’S GREATEST SKYLINE, 1881 to the Present

For the ironworkers

Prologue: Of Steel and Men

PART I

The Hole

1 Some Luck

2 The Man On Top (1901)

3 The New World (2001)

4 The Walking Delegate (1903)

5 Mondays (2001)

PART II

The Bridge

6 Kahnawake

7 Cowboys of the Skies

8 Fish

PART III

The Fall

9 The Old School

10 The Towers

11 Burning Steel

12 Topping Out

Sources

Acknowledgements

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

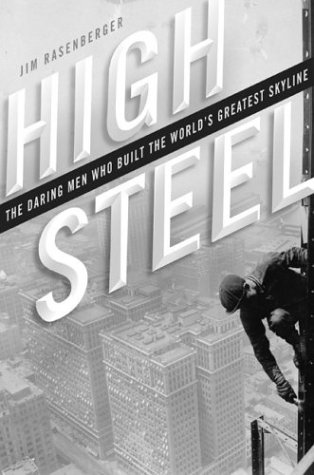

Ironworkers atop the Woolworth Building, 1912.

(Brown Brothers)

“…high growths of iron, slender, strong, light, splendidly uprising toward clear skies….”

—W

ALT

W

HITMAN

“Mannahatta,” 1881

O

nly a poet—maybe only Walt Whitman himself, for that matter—could have described the skyline of Manhattan in 1881 with such delirious hyperbole. High growths of iron? The highest point on the island in 1881 was the steeple of Trinity Church, built in 1846 and rising 284 feet over Broadway. The vast majority of secular buildings rose just four or five stories, and the tallest rose a mere ten stories. Even these were remarkably chunky structures, built of thick masonry or dense cast iron, hardly “light” or “slender.” They soared like penguins.

But if Whitman’s description seems a bit overwrought by today’s standards, it was also prophetic. New York was on the verge of enormous physical change in 1881. The main evidence of this stood in the East River, in the form of two stone towers rising from the cur

rents, one near Manhattan’s shore, the other near Brooklyn’s. The towers were high, startlingly high, each looming 276 feet over the river; but it wasn’t the towers that made the Brooklyn Bridge so remarkable. It was the great steel cables draped between them, and the steel beams suspended from the harp-like web of steel wires. This was the part of the bridge that really mattered, the part that made it a bridge, unleashed from earth if not the laws of physics: steel.

Americans did not invent steel, but steel, in many ways, invented twentieth-century America. Cars, planes, ships, lawn mowers, office desks, bank vaults, swing sets, toaster ovens, steak knives—to live in twentieth-century America was to live in a world of steel. By mid-century, 85 percent of the manufactured goods in the United States contained steel, and 40 percent of wage earners owed their jobs, at least indirectly, to the steel industry. Steel was everywhere. Most evidently, and most awesomely, it was in the cities, ascending hundreds of feet above the earth in the form of steel-frame skyscrapers.

The first skyscrapers began to appear in Chicago in the mid-1880s, a year or so after the Brooklyn Bridge opened to traffic. The new buildings turned the old rules of architecture inside out: instead of resting their weight on thick external walls of brick or stone, they placed it on an internal framework—a “skeleton”—of steel columns and beams. The effect was as if buildings had evolved overnight from lumbering crustaceans into lofty vertebrates. Walls would still be necessary for weather protection and adornment, but structurally they’d be almost incidental. The steel frame made building construction more efficient and more economical, and it had a less pragmatic—yet more significant—effect. It gave humans the ability to rise as high as elevators and audacity could carry them.

The steel-frame skyscraper was born in Chicago, but New York is where it truly came of age. By 1895, Manhattan’s summit had doubled to 20 stories, then it doubled again, then again—all before 1930

and all made possible by steel. And as skyscrapers sprang up from the bedrock, new steel bridges reached out to Brooklyn, to Queens, to the mainland across the Hudson, connecting the city so seamlessly to the world beyond that New Yorkers would soon forget they lived on an island.

In 1970, the summit of the city rose one last time, to 110 stories, on the stacked columns of two identical buildings in lower Manhattan. A stone’s throw from Trinity Church and a short stroll from the Brooklyn Bridge, the twin towers of the World Trade Center seemed to herald a remarkable new age of building. They were so high—ten times as high as the “high growths of iron” Walt Whitman admired in 1881—they literally disappeared, some days, into the clouds.

The astonishing ascendancy of New York City’s skyline has been recounted before, often and well. Several of its icons—the Flatiron Building, the Woolworth Building, the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building—have achieved a kind of celebrity usually reserved for Hollywood film stars and heads of state, while their architects and builders have basked in reflected glory. Strangely, though, one group of key players is usually neglected in the telling of the skyline’s drama: the men who risked the most and labored the hardest to make it happen. Called ironworkers, or, more specifically,

structural

ironworkers, these are the brave and agile men who raised the steel into the sky: the generations of Americans and Newfoundlanders and Mohawk Indians who balanced on narrow beams high above the city to snatch steel off incoming derricks or crane hooks and set it in place—who shoved it, prodded it, whacked it, reamed it, kicked it, shoved it some more, swore at it, straddled it, pounded it mercilessly, and then riveted it or welded it or bolted it up and went home. That was on a good day. On a bad day, they went to the hospital or the morgue. Steel is an unforgiving material and, given any chance, bites back. It was a lucky ironworker who made it to retirement without losing a few fingers or breaking a few bones. And

then, of course, there was always the possibility of falling. Much ironwork was done hundreds of feet in the air, where a single false step meant death. Steel was the adversary that made them sweat and bleed. It was gravity, though, that usually killed them.

This is the story of the ironworkers who built New York—and are building it still. Without idealizing them, it’s fair to say that they are a remarkable breed. What makes them remarkable isn’t just their daring or acrobatics; it’s their whole way of life. History lives through them by way of their genealogies. Many come from a close-knit group of families, multigenerational dynasties of New York ironworkers. They are the sons and grandsons and great-grandsons of the men who built the icons of the past. They are the Montours, the Deers, the Diabos, and the Beauvais from the Kahnawake Mohawk Reserve near Montreal. They are the Kennedys, the Lewises, the Doyles, the Wades, and the Costellos from a small constellation of seaside towns in Newfoundland. They are the Collinses, the Donohues, the Johnsons, the Andersons, and the McKees, whose grandfathers immigrated to New York from Germany and Scandinavia and Ireland. When a young man from one of these families looks out over the skyline and says, “My family built this city,” his brag is deserved.

Today’s ironworkers are, in many respects, cultural relics. They live at odds with the prevailing trends of twenty-first-century American culture, or at least American culture as prescribed by glossy magazines and morning television shows. They drink too much, smoke too much, and practice few of the civilities of the harassment-free workplace. As gender roles become less defined, the ironworkers, virtually all of them men, continue to revel in a cocoon of full-blown masculine camaraderie. Education levels have increased across the board in America, but the education of most ironworkers stops at high school. Unionism is in decline, with just 11 percent of American workers still enrolled in labor unions at the start of the twenty-first century, but New York ironworkers remain avid and unabashed unionists. The labor force has turned en masse from

manual work to high-tech, sedentary work in ergonomically correct settings, but ironworkers continue to depend on muscle and stamina and a capacity to endure a certain amount of pain. And as Americans become increasingly averse to risk, ironworkers continue to risk their lives every day they go to work.

On a cold afternoon several winters ago, I climbed out of a subway station at the corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue and looked up to see a tall young man in a gray sweatshirt walking a pencil-thin beam hundreds of feet over Times Square. The economy was still booming, the World Trade Center was still standing. Christmas was a few weeks away. Down on the ground, Salvation Army bells jingled and people pushed along the sidewalks, dashing into the intersection. Up there, the young man seemed oblivious to all of this. He walked with a smooth stride, his arms loose at his side. For all the care he displayed, he might have been strolling down a country lane.

I never spoke to Brett Conklin that afternoon—I never spoke to him, in fact, until after he fell—but a few weeks later I saw him again, this time in a photograph. I’d written an article about ironworkers for the

New York Times

. The newspaper had dispatched a photographer to the building on Times Square where Brett worked, and when the article appeared it featured a large photograph of Brett on the front cover. The photograph shows a handsome young man, his hard hat turned rakishly backwards, standing on a beam at what appears to be the edge of the building. He’s looking down with an expression that is—what?—fearless, contemplative, defiant. Or maybe none of those. It’s an expression that I find impossible to read. I suppose what it is, really, is the expression of a young man whose life is about to change.

Icarus high up on Empire State

, by Lewis Wickes Hine, 1931.

(

New York Public Library/Art Resource, New York)