History of the Second World War (16 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

This statement of Warlimont’s gains significance when related to the last sentence in Halder’s diary note of the 24th, already quoted. Moreover, Guderian stated that the order came down to him from Kleist, with the words: ‘Dunkirk is to be left to the Luftwaffe. If the conquest of Calais should raise difficulties that fortress likewise is to be left to the Luftwaffe.’ Guderian remarked: ‘I think that it was the vanity of Goring which caused that fateful decision of Hitler’s.’

At the same time there is evidence that even the Luftwaffe was not used as fully or as vigorously as it could have been — and some of the air chiefs say that Hitler put the brake on again here.

All this caused the higher circles to suspect a political motive behind Hitler’s military reasons. Blumentritt, who was Rundstedt’s operational planner, connected it with the surprising way that Hitler had talked when visiting their headquarters:

Hitler was in very good humour, he admitted that the course of the campaign had been ‘a decided miracle’, and gave us the opinion that the war would be finished in six weeks. After that he wished to conclude a reasonable peace with France, and then the way would be free for an agreement with Britain.

He then astonished us by speaking with admiration of the British Empire, of the necessity for its existence, and of the civilisation that Britain had brought into the world. He remarked, with a shrug of the shoulders, that the creation of its Empire had been achieved by means that were often harsh, but ‘where there is planing, there are shavings flying’. He compared the British Empire with the Catholic Church — saying they were both essential elements of stability in the world. He said that all he wanted from Britain was that she should acknowledge Germany’s position on the Continent. The return of Germany’s lost colonies would be desirable but not essential, and he would even offer to support Britain with troops if she should be involved in any difficulties anywhere. He remarked that the colonies were primarily a matter of prestige, since they could not be held in war, and few Germans could settle in the tropics.

He concluded by saying that his aim was to make peace with Britain on a basis that she would regard as compatible with her honour to accept.*

* pp. 200-1.

In subsequent reflection on the course of events, Blumentritt’s thoughts often reverted to this conversation. He felt that the ‘halt’ had been called for more than military reasons, and that it was part of a political scheme to make peace easier to reach. If the B.E.F. had been captured at Dunkirk, the British might have felt that their honour had suffered a stain which they must wipe out. By letting it escape Hitler hoped to conciliate them.

Since this account comes from generals who were highly critical of Hitler, and admit that they themselves wanted to finish off the British Army, it is of the more significance. Their account of Hitler’s talks at the time of Dunkirk fits in with much that he himself wrote earlier in

Mein Kampf —

and it is remarkable how closely he followed his own testament in other respects. There were elements in his make-up which suggest that he had a mixed love-hate feeling towards Britain. The trend of his talk about Britain at this time is also recorded in the diaries of Ciano and Halder.

Hitler’s character was of such complexity that no simple explanation is likely to be true. It is far more probable that his decision was woven of several threads. Three are visible — his desire to conserve tank strength for the next stroke; his long-standing fear of marshy Flanders; and Goring’s claims for the Luftwaffe. But it is quite likely that some political thread was interwoven with these military ones in the mind of a man who had a bent for political strategy and so many twists in his thought.

The new French front along the Somme and the Aisne was longer than the original one, while the forces available to hold it were much diminished. The French had lost thirty of their own divisions in the first stage of the campaign, besides the help of their allies. (Only two British divisions remained in France, though two more that were not fully trained were now sent over.) In all, Weygand had collected forty-nine divisions to cover the new front, leaving seventeen to hold the Maginot Line. Not much could be done to fortify the front in the short time available, and the shortage of forces counteracted the belated attempt to apply the method of defence in depth. As most of the mechanised divisions had been lost or badly depleted there was also a lack of mobile reserves.

The Germans, by contrast, had brought their ten panzer divisions up to strength again with relays of fresh tanks, while their 130 infantry divisions were almost untouched. For the new offensive the forces were redistributed, two fresh armies (the 2nd and 9th) being inserted to increase the weight along the Aisne sector (between the Oise and the Meuse), and Guderian was given command of a group of two panzer corps that was moved to lie up in readiness there. Kleist was left with two panzer corps, to strike from the bridgeheads over the Somme at Amiens and Peronne respectively, in a pincer-move aimed to converge on the lower reach of the Oise near Creil. The remaining armoured corps, under Hoth, was to advance between Amiens and the sea.

The offensive was launched on June 5, initially on the western stretch between Laon and the sea. Resistance was stiff for the first two days, but on the 7th the most westerly armoured corps broke through on the roads to Rouen. The defence then collapsed in confusion, and the Germans met no serious resistance in crossing the Seine on the 9th. But it was not here that they intended their decisive manoeuvre, so they paused, which was fortunate for the small British force, under General Alan Brooke, most of which was thus enabled to achieve a second evacuation when the French capitulated.

Kleist’s pincer-stroke did not, however, go according to plan. The right pincer eventually broke through on the 8th but the left pincer, from Peronne, was hung up by tough opposition north of Compiegne. The German Supreme Command then decided to pull back Kleist’s group and switch it east to back up the breakthrough that had been made in Champagne.

The offensive there did not open until the 9th, but then the collapse came quickly. As soon as the infantry masses had forced the crossings, Guderian’s tanks swept through the breach towards Chalons-sur-Marne, and then eastward. By the 11th Kleist was widening the sweep and crossed the Marne at Chateau-Thierry. The drive continued at racing pace, over the Plateau de Langres to Besancon and the Swiss frontier — cutting off all the French forces in the Maginot Line.

As early as the 7th Weygand advised the Government to ask for an armistice without delay, and next day he announced that ‘the Battle of the Somme is lost’. The Government, though divided in opinion, hesitated to yield, but on the 9th decided to leave Paris. It wavered between a choice of Brittany and Bordeaux, and then went to Tours as a compromise. At the same time Reynaud sent off an appeal to President Roosevelt for support, in which he declared: ‘We shall fight in front of Paris; we shall fight behind Paris; we shall shut ourselves up in one of our provinces, and, if we should be driven out, we shall go to North Africa. . . .’

On the 10th Italy declared war. Mussolini had been belatedly offered various colonial concessions, but spurned them in the hope of improving his position with Hitler. An Italian offensive, however, was not launched until ten days later, and was then easily held in check by the weak French forces.

On the 11th Churchill flew to Tours in a vain effort to encourage the French leaders. Next day Weygand addressed the Cabinet, told them the battle was lost, blamed the British for both defeats, and then declared: ‘I am obliged to say clearly that a cessation of hostilities is compulsory.’ There is little doubt that he was correct in this estimate of the military situation, for the French armies were now splitting up into fragments, and most of these made little attempt to stand, but merely dissolved in a southerly flow. The Cabinet was now divided between capitulation and a continuance of the war from North Africa, but only decided to move itself to Bordeaux, while instructing Weygand to attempt a stand on the Loire.

The Germans entered Paris on the 14th and were driving deeper on the flanks. On the 16th they reached the Rhone valley. Meanwhile Weygand had continued his pressure for an armistice, backed by all the principal commanders. In a last-hour effort to avert this decision, and ensure a stand in Africa, Churchill made a far-reaching proposal for a Franco-British Union. It made little impression, except to produce irritation. A vote was taken upon it, a majority of the French Cabinet rejected it, and it turned into a decision for capitulation. Reynaud resigned, whereupon a new Cabinet was formed by Marshal Petain, and the request for the armistice was transmitted to Hitler on the night of the 16th.

Hitler’s terms were delivered to the French envoys on the 20th — in the same railway coach in the forest of Compiegne wherein the German envoys had signed the armistice of 1918. The German advance proceeded beyond the Loire while discussion continued, but on the 22nd the German terms were accepted. The armistice became effective at 1.35 a.m. on June 25, after an accompanying armistice with Italy had been arranged.

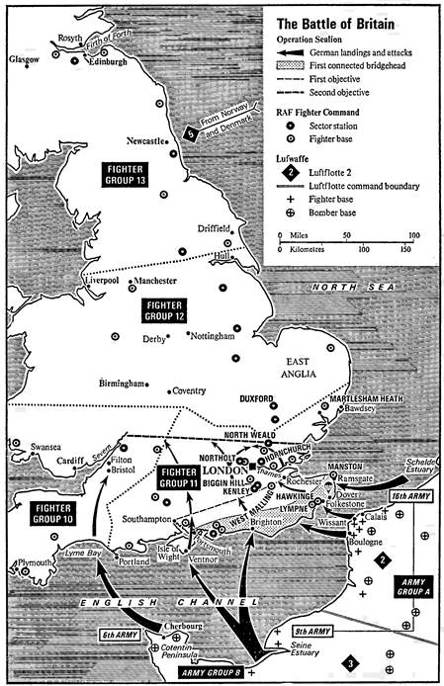

CHAPTER 8 - THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN

Although the war started on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland, and this was followed two days later by the successive British and French declarations of war on Germany, it is one of the most extraordinary features of history that Hitler and the German Supreme Command had made no plans or preparations to deal with Britain s opposition. Stranger still, nothing was done during the long interval, of nearly nine months, before the great German offensive in the West was launched in May 1940. Nor were any plans made even after France was obviously crumbling and its collapse assured.

It thus becomes very clear that Hitler was counting on the British Government’s agreement to a compromise peace on the favourable terms he was disposed to grant, and that for all his high ambitions he had no wish to press the conflict with Britain to a decisive conclusion. Indeed, the German generals were given to understand by Hitler that the war was over, while leave was granted and part of the Luftwaffe was shifted to other potential fronts. Moreover, on June 22 Hitler ordered the demobilisation of thirty-five divisions.

Even when Churchill’s rejection of any compromise was made emphatic, and his determination to pursue the war was manifest, Hitler still clung to the belief that it was a bluff, and felt that Britain was bound to recognise ‘her militarily hopeless situation’. That hope was slow to fade. It was not until July 2 that he even ordered a study of the problem of overcoming Britain by invasion, and he still sounded a note of doubt about the need when at last on July 16, two weeks later, he ordered preparation of such an invasion, christened ‘Operation Sealion’. He did say, however, that the expedition must be ready by mid-August.

Even then Hitler’s underlying reservations — or, at the least, his split mind — were shown in the fact that he told Halder on July 21 that he intended to turn and tackle the problem of Russia, if possible launching an attack on her that autumn. On the 29th, at O.K.W., Jodl told Warlimont that Hitler was determined on war against Russia. Several days earlier, the operational staff of Guderian’s panzer group had been sent back to Berlin to prepare plans for the employment of the panzer forces in such a campaign.

When France collapsed the German Army was in no way prepared for such an undertaking as the invasion of England. The staff had not contemplated it, let alone studied it; the troops had been given no training for seaborne and landing operations; and nothing had been done to build landing-craft for the purpose. So all that could be attempted was a hurried effort to collect shipping, bring barges from Germany and the Netherlands to the Channel ports, and give the troops some practice in embarking and disembarking. It was only the temporary ‘nakedness’ of the British forces, after losing most of their arms and equipment in France, that offered such a hasty improvisation the possibility of success.

The main part in the operation was given to Field-Marshal von Rundstedt and his Army Group A, which was to employ the 16th Army (General Busch) on the right and the 9th Army (General Strauss) on the left. Embarking in the various harbours between the estuaries of the Scheldt and the Seine, seaborne forces were to converge on the south-east coast of England between Folkestone and Brighton, while an airborne division was to capture the cliff-covered Dover-Folkestone area. Under this ‘Sealion’ plan, ten divisions would be landed in the first wave over a period of four days to establish a wide bridgehead. After about a week the main advance inland would begin, its first objective being to gain the high ground along an arc from the Thames estuary to Portsmouth. In the next stage, London was to be cut off from the west.

A subsidiary operation was to be mounted by the 6th Army (Field-Marshal von Reichenau) of Army Group B, with three divisions in the first wave, to sail from Cherbourg and land in Lyme Bay west of Portland Bill for a push northward to the Severn estuary.