History of the Second World War (26 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

On December 5 Hitler received Halder’s report on the eastern plan, and on the 18th issued ‘Directive No. 21 — Case Barbarossa.’ It opened with the decisive statement: ‘The German armed forces must be prepared to crush Soviet Russia in a quick campaign before the end of the war against England.’

For this purpose the Army will have to employ all available units, with the reservation that the occupied countries will have to be safeguarded against surprise attacks. The concentration of the main effort of the Navy remains unequivocally against England!

If the occasion arises, I shall order the concentration of troops for action against Soviet Russia eight weeks before the intended beginning of operations, Preparations requiring more time are — if this has not already been done — to begin immediately, and are to be completed by May 15, 1941. [This was considered the earliest possible date for suitable weather conditions.] Great caution has to be exercised so that the intention to attack will not be recognised. . . .

The mass of the Russian Army in Western Russia is to be destroyed in daring operations by driving four deep wedges with tanks, and the retreat of the enemy’s battle-ready forces into the wide spaces of Russia is to be prevented.

The directive went on to say that if these results did not suffice to cripple Russia, her last industrial area in the Urals could be eliminated by the Luftwaffe. The Red Fleet would be paralysed by the capture of the Baltic bases. Rumania would help by pinning down the Russian forces in the south and by providing auxiliary service in the rear — Hitler had sounded the new Rumanian dictator, General Antonescu, in November about participating in an attack on Russia.

The phrase ‘if occasion arises’ has an indefinite sound, but there seems little doubt that Hitler’s intention was fixed. The qualification may be explained by a later passage in the directive: ‘All orders which shall be issued by the High Commanders in accordance with this instruction have to be clothed in such terms that they may be taken as measures of precaution in case Russia should change her present attitude towards ourselves.’ The plan was to be cloaked by an elaborate deception programme, and it came naturally to Hitler to take the lead in this respect.

Moreover, deception had to be practised on his own people as well as on the enemy. So many of those to whom he broached the project were troubled about the risks of invading Russia, especially as it meant a two-front war, that he thought it wise to wear the appearance of reserving a final decision. This would give them time to become acclimatised to the change of wind, while giving him time to produce more persuasive evidence of Russia’s hostile intentions. His generals, in particular, expressed such doubts that he was anxious about the effect of their half-heartedness. Although he could command obedience under the oath they had given him, that would not suffice to produce in their minds the determination required for success. As he had to make use of them as professional instruments it was necessary to convince them.

On January 10 a fresh treaty was signed with Russia that embodied the results of the November conversations with Molotov on frontier and economic questions. The surface was thus made to look smoother. But Hitler’s private view was expressed in his comment that Stalin was an ‘ice-cold blackmailer’. At the same time disquieting reports came from Rumania and Bulgaria about Russian activity there.

On the 19th Hitler was visited by Mussolini, and at this meeting spoke of his difficulties with Russia. He did not reveal his own offensive plans, but significantly mentioned that he had received a strong protest from Russia about the concentration of German troops in Rumania. An important sidelight on his own thought was contained in his remark: ‘Formerly Russia would have been no danger at all, for she cannot imperil us in the least; but now in the age of airpower, the Rumanian oilfields can be turned into an expanse of smoking debris, by air attack from Russia and the Mediterranean, and the life of the Axis depends on these oilfields.’ That was also his argument to his own generals who suggested that, even if the Russians were intending an invasion, the risk could be adequately met by increasing the defensive strength of the German forces behind the frontier, instead of launching an offensive into Russia.

On February 3 Hitler approved the final text of the ‘Barbarossa’ plan, following a conference of his military chiefs at Berchtesgaden, in which the points of the plan were unfolded. Keitel gave an estimate of the enemy’s strength in western Russia as approximately 100 infantry divisions, twenty-five cavalry divisions, and the equivalent of thirty mechanised divisions. This was close to the mark, for when the invasion was launched the Russians had available in the west 88 infantry divisions, seven cavalry divisions, and fifty-four tank and motorised divisions. Keitel then said that the German strength would be not quite so large, ‘but far superior in quality’. Actually the invading armies comprised 116 infantry divisions (of which fourteen were motorised), a cavalry division, and nineteen armoured divisions — besides nine lines-of-communication divisions. The enumeration of strength was not calculated to allay the disquiet of the generals, for it showed they were embarking on a great offensive without any odds in their favour, and with marked adverse odds in the decisive element — the armoured forces. It was clear that the planners were gambling heavily on the superiority of quality.

Keitel continued: ‘Russian operational intentions are unknown. There are no strong forces at the frontier. Any retreat could only be of small extent, since the Baltic States and the Ukraine are vital to the Russians for supply reasons.’ That seemed reasonable at the time, but proved an over-optimistic assumption.

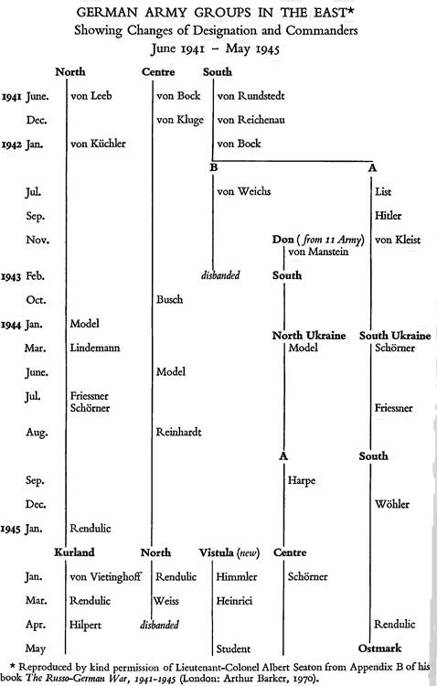

The invading forces were to be divided into three army groups, and their operational tasks were outlined. The northern one (under Leeb) was to attack from East Prussia through the Baltic states towards Leningrad. The central one (under Bock) was to strike from the Warsaw area towards Minsk and Smolensk, along the Moscow highway. The southern one (under Rundstedt) was to attack south of the Pripet Marshes, extending down to Rumania, with the Dnieper and Kiev as its objectives. The main weight was to be concentrated in the central group, to give it a superiority of strength. It was reckoned that there would be bare equality in the north, and an inferiority of strength in the southern sector.

In his survey, Keitel remarked that Hungary’s attitude was still doubtful, and emphasised that arrangements with those countries that might co-operate with Germany could be made only at the eleventh hour, for reasons of secrecy. Rumania, however, had to be an exception to this rule, because her co-operation was ‘vital’. (Hitler had just previously seen Antonescu again, and asked him to permit German troops to pass through Rumania to support the Italians in Greece, but Antonescu had hesitated, arguing that such a step might precipitate a Russian invasion of Rumania. At a third meeting Hitler promised him not only the return of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, but the possession of a stretch of southern Russia ‘up to the Dnieper’ as a recompense for Rumanian aid in the attack.)

Keitel added that the Gibraltar operation was no longer possible as the bulk of the German artillery had been sent cast. While ‘Operation Sealion’ had also been shelved, ‘everything possible should be done to maintain the impression among our own troops that the invasion of Britain is being further prepared’. To spread the idea certain areas on the Channel coast and in Norway were to be suddenly closed, while as a double bluff the eastward concentration was to be represented as a deception exercise for the landing in England.

The military plan was coupled with a large-scale economic ‘Plan Oldenburg’ for the exploitation of the conquered Soviet territory. An Economic Staff was created, entirely separate from the General Staff. A report of May 2, on its examination of the problem, opened with the statements: ‘The war can only be continued if all armed forces are fed by Russia in the third year of the war. There is no doubt that many millions of people will starve to death in Russia if we take out of the country the things necessary for us.’ It is not clear whether this was simply a cold-blooded scientific statement or intended as a warning against excessive aims and demands. The report went on to say: ‘The seizure and transfer of oil seeds and oil cakes are of prime importance; grain is only secondary.’ An earlier report by General Thomas, Chief of the War Economy Department of the OKW (Armed Forces General Staff), had pointed out that the conquest of all European Russia might relieve Germany’s food problem, if the transport problem could be solved, but would not meet other important parts of her economic problem — the supply of ‘India rubber, tungsten, copper, platinum, tin, asbestos, and manila hemp would remain unsolved until communication with the Far East can be assured’. Such warnings had no effect in restraining Hitler. But another conclusion, that ‘the Caucasian fuel supply is indispensable for the exploitation of the occupied territories’, was to have a very important effect in spurring him to extend his advance to the point of losing his balance.

The ‘Barbarossa’ plan suffered even worse from a preliminary upset that had far-reaching delayed effect. This was due to the psychological effect, on Hitler, of the double diplomatic rebuff he received from Greece and Yugoslavia, with British backing.

Before striking at Russia Hitler wanted to have his right shoulder free — from British interference. He had hoped to secure control of the Balkans without serious fighting — by practising armed diplomacy. He felt that after his victories in the West it ought to succeed more easily than ever. Russia had smoothed his way into Rumania by her push into Bessarabia; Rumania had fallen into his arms on the recoil. The next step also proved easy. On March 1 the Bulgarian Government swallowed his bribe and committed itself to a pact whereby the German forces were allowed to move through its territory and take up positions on the Greek frontier. The Soviet Government broadcast its disapproval of this departure from neutrality, but its abstention from anything more forcible made Hitler more sure that Russia was not ready for war.

The Greek Government was less responsive to Hitler’s diplomatic approaches, as was natural after the way Greece had been invaded by his Axis partner. Nor did the Greek Government wilt at his threats. The spirit of the Greek people had been aroused and was heightened by their success in repelling Mussolini’s invasion. In February arrangements had been made for their reinforcement by British troops, and these began to land a few days after the Germans’ entry into Bulgaria.

The challenge provoked Hitler to put under way his attack on Greece — which was launched a month later. This was a needless diversion from his main path. For the force that Britain could furnish was not large enough to be capable of doing more than cause a slight irritation to his right shoulder, and the Greeks were fully occupied in dealing with the Italians.

The adverse effect on his Russian plan was intensified by the events in Yugo-Slavia. Here his approach had a favourable start. Under German pressure the Yugo-Slav Government agreed to link itself to the Axis on a compromise basis of being released from military obligations, but with the secret condition that the Belgrade-Nish rail line towards the Greek frontier was to be available for German troops. The Yugo-Slav representatives signed the Pact on March 25. Two days later a military coup d’etat was carried out in Belgrade by General Simovich, the Chief of the Yugo-Slav Air Force, and a group of young officers. They seized control of the radio station and the telephone centre, turned out the Government, established a new one under Simovich’s leadership, and then defied the German demands. British agents had helped to foster the plot, and when the news of its success reached London Churchill announced in a speech: ‘I have great news for you and the whole country. Early this morning Yugo-Slavia found its soul.’ He went on to declare that the new Government would receive ‘all possible aid and succour’ from Britain.

The coup revolutionised the Balkan situation. Hitler could not tolerate such an affront, and Churchill’s glee infuriated him. He at once decided to invade Yugo-Slavia as well as Greece. The necessary moves were made so swiftly that he was able to launch the blow ten days later, on April 6.

The direct results of this Balkan defiance were pitiful. Yugo-Slavia was overrun within a week, and her capital devastated by the opening air attack. Greece was overrun in just over three weeks, and the British force hustled back into its ships, after a long retreat with little fighting. It had been out-manoeuvred at each stage. The outcome reflected on Churchill’s judgement, and on that of those who supported him by declaring the feasibility of a successful military intervention — in view not merely of Britain’s loss of credit but of the vast burden of misery that was cast on the people of Yugo-Slavia and Greece. The sense of being let down had lasting effects. Moreover, it is one of the ironies of history that the ultimate issue of Churchill’s initiative was the resurrection of Yugo-Slavia in the form of a state hostile to all he represented.