History of the Second World War (69 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

Mussolini vented his spleen at the loss of Tripoli by recalling Bastico and dismissing Cavallero — who was replaced by General Ambrosio. Meanwhile Rommel had received a telegram, on January 26, notifying him that in view of the bad state of his health he would be relieved of command after consolidating his new position in the Mareth Line, and that his army was to be renamed the First Italian Army, with General Giovanni Messe as its commander. He was, however, left to choose the date of hand-over and departure — a concession of which he took advantage, to the Allies’ detriment.

Rommel was a sick man and the strain of the last three months had not improved his condition. But he was to show, in February, that he still had a strong kick in him.

Instead of being dismayed by the Americans’ close approach to his line of retreat through southern Tunisia, he scented a fine opportunity of striking there before Montgomery could again catch up with him. Although the Mareth defences were poor, they did provide an obstacle to tank attack and should at least delay Montgomery. Moreover, Rommel’s own strength was reviving. In retreating westward, he had come nearer to his supply ports and had gained more than he had lost during the long retreat, while in number of troops he had now as many as when the autumn Battle of Alamein opened. At the time he arrived in Tunisia his army totalled close on 30,000 Germans,* and about 48,000 Italians — although this roll included the 21st Panzer Division, which had been sent back to the Gabes-Sfax area, and also the Centauro Armoured Division, which was being sent to guard the El Guettar defile, facing the American position at Gafsa. In armament, however, the situation was not nearly so good — the German units were about one-third of full strength in tanks, one-fourth in anti-tank guns, and one-sixth in artillery. Moreover, out of approximately 130 tanks, less than half were fit for action. Nevertheless the overall situation was relatively better than it was likely to become once Montgomery had time to make full use of the port of Tripoli, and mass his superior strength on the Tunisian frontier. Rommel was eager to profit by the interval.

* This was about half their full strength, on establishment scale — the same as it had been when the Alamein battle began.

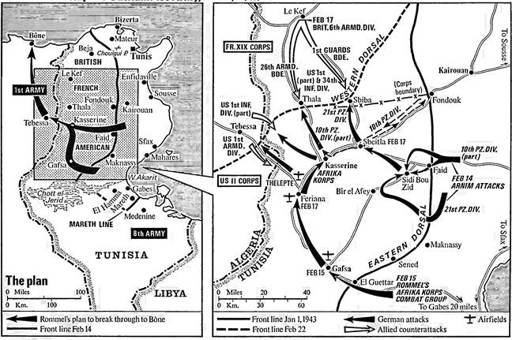

So he now planned a double stroke in Napoleonic style to exploit what strategists term the interior ‘lines’ theory — taking advantage of a central position, between two converging enemy forces, to strike at one of them before the other can aid it. If he could crumple up the Americans poised behind him, he would have both hands free to tackle Montgomery’s Eighth Army which was now thinned out by the way its lines of supply had been stretched.

It was a brilliant plan, but Rommel’s biggest handicap in putting it into effect was that it had to depend largely on forces which were not under his own control. He could spare only enough from the Mareth Line to form one large combat-group, less than half the size of a division, under Colonel von Liebenstein. His famous and trusty 21st Panzer Division, sent back to Tunisia earlier, was right on the spot where he wanted to strike, but it had passed under the command of General von Arnim’s army. It was thus left to Arnim, at the outset, to decide the aims of the main thrust and the strength that should be employed, while Rommel was limited to helping it on so far as he could.

The American 2nd Corps (which included a French division) was the target of this counterstroke. Its front covered ninety miles, but was really focused on the three routes through the mountains to the sea, with spear-heads at the passes near Gafsa, Faid, and Fondouk — where it linked up with the French 19th Corps under General Koeltz. These passageways were so narrow that the occupiers felt secure, and the attention of the Allied higher command had been largely absorbed in checking a series of Axis probing attacks in the sector north of Fondouk.

But at the end of January, the veteran 21st Panzer made a sudden spring at the Faid Pass, overwhelmed the poorly armed French garrison there before American aid belatedly arrived, and thus gained a sally-port for the bigger attack to follow. This coup made the Allied higher commanders suspect that such an offensive was being planned by the enemy, but they did not expect it where it came. Regarding the preliminary Faid stroke as a diversion, they believed that the attack would be delivered near Fondouk. As General Omar Bradley remarked in his memoirs: ‘This belief came to be a near-fatal assumption.’ It prevailed both at Eisenhower’s headquarters and at those of the British First Army, under Anderson, who had now been placed in charge of the whole Allied front in Tunisia pending the arrival of Alexander. The latter had been appointed at the Casablanca Conference to command, under Eisenhower, the new 18th Army Group made up of the First and Eighth Armies, which was to be constituted when the latter entered Tunisia. To guard the expected line of attack, Anderson was led to keep Combat Command B, with half the American armour, back in reserve behind Fondouk. That miscalculation helped to ease the way for the enemy’s advance.

By the beginning of February the Axis forces in Tunisia had risen to a total of 100,000 — 74,000 Germans and 26,000 Italians — which was a much better ratio to the Allied strength than it had been in December, or was likely to be when the Allied concentration was completed. About 30 per cent were administrative personnel. The available strength in armour, which was almost entirely dependent on the German contribution, was just over 280 tanks — 110 with the 10th Panzer Division, 91 with the 21st Panzer Division (exactly half the full complement on the existing establishment scale), a dozen Tigers in a special unit, while Rommel was bringing a battalion of twenty-six tanks in Liebenstein’s combat-group to reinforce twenty-three surviving Italian tanks of the Centauro Division on the Gafsa road. This total fell a long way short of the Allied strength, and even if the whole of it was employed would not provide a numerical superiority on the intended front of attack in the southerly part of Tunisia. For the U.S. 1st Armored Division supporting that sector, although still short of full strength, had about 300 tanks in operation — although ninety were Stuarts — and thirty-six tank destroyers, and was much stronger in artillery than a panzer division.* But to Rommel’s disappointment only part of the 10th Panzer Division (with one medium tank battalion and a company of four Tigers) was sent down to reinforce the 21st, and merely for the opening phase, as Arnim was planning to use the 10th for a thrust he planned to deliver farther north.

* These figures, from the records, significantly show how fallacious it can be to compare Allied and Axis strength in terms of the number of ‘divisions’ engaged on either side — as the Allied commanders, and many of the official historians, have done in their accounts. At this period the tank establishment of an American armoured division (390 tanks) was more than twice as large as that of a normal German panzer division (180). But the actual ratio was usually greater, as the Germans had more difficulty in making up shortages. As can be seen, even the depleted 1st Armored Division had approximately three times as many tanks as the average of the panzer divisions opposed to it.

The establishment of a British armoured division had recently been reduced to approximately 270 tanks, exclusive of specialised ones, and American divisions, with certain exceptions, were reorganised on a similar scale later in the year. But in 1944 the British armoured divisions were raised to a scale of 310, by equipping their reconnaissance unit with tanks instead of armoured-cars — and the actual strength of the Allied armoured divisions, in number of tanks available for action, was usually two to three times as large as the German. To maintain a balance the Germans had to depend on a qualitative advantage.

Rommel’s Attempt to Outflank 1st Army.

On February 14 the real offensive opened, when the 21st Panzer Division pounced again, from Faid, together with the contingent from the 10th. Arnim’s deputy, General Ziegler, was in immediate charge of the attack. While the two small combat-groups from the 10th Panzer Division swept forward from the Faid Pass, opening out like pincer arms to grip the advanced part of the U.S. 1st Armored Division — Combat Command A — two more from the 21st Panzer Division (each with a tank battalion as its core) made a wider circuit southward, during the night, to outflank and trap the Americans. Although fragments managed to escape before the ring was closed, around Sidi Bou Zid, loss of equipment was very heavy. The battlefield was strewn with blazing American tanks, forty being lost in this action. Next morning Combat Command C was hastily sent forward to deliver a counterattack, and was promptly trapped by encircling German moves, only four of its tanks getting away. Thus two fine battalions of medium tanks had been wiped out successively in these piecemeal fights against the enemy’s skilful concentration of superior force from inferior resources. Fortunately for the Allies, the Germans were slow in their follow up.

Rommel had urged Ziegler, on the 14th, to drive on during the night and exploit the opening success to the full — ‘The Americans had no practical battle experience, and it was for us to instil them with a deep inferiority complex from the outset.’ But Ziegler felt bound to wait until he had obtained Arnim’s authorisation, and it was only on the 17th that he pushed forward twenty-five miles to Sbeitla, where the Americans had rallied. There, in consequence, the Germans met stiffer opposition, as Combat Command B (now led by Brigadier-General Paul Robinett) had been rushed south. It kept the Germans at bay until late in the afternoon, and helped to cover the retreat of the battered remnants of the other two Combat Commands before withdrawing itself — as part of a general wheel back of the Allies’ southern wing, ordered by Anderson, to the line of the Western Dorsal mountain ridges. Although the Germans’ entry into Sbeitla had been delayed, their total bag had risen to more than a hundred tanks and nearly three thousand prisoners.

Meanwhile the combat-group brought up by Rommel, and directed against the Allies’ extreme southern flank at Gafsa, had pushed into that road-centre when it was evacuated on the 15th. Accelerating its pace, and swinging north-west, it advanced fifty miles farther by the 17th, through Feriana, and captured the American airfields at Thelepte. So it had now come up almost level with the 21st Panzer but thirty-five miles to the west of it, and thus closer to the Allies’ communications. Alexander — who arrived on the scene that day, and took over charge of both armies on the 19th — said in his Despatch that in the ‘confusion of the retreat American, French, and British troops had become inextricably mingled, there was no co-ordinated plan of defence and definite uncertainty as to command.’ Rommel heard that the Allies had set fire to their supply depots at Tebessa, forty miles on beyond the next mountain range. That appeared to him clear evidence that they were ‘getting jittery’.

Now came the real turning point — although the Allied commanders imagined it was three days later. Rommel wanted to exploit the confusion and panic by a combined drive with all the available mechanised forces through Tebessa. He felt that such a deep thrust towards the Allies’ main communications would force the British and Americans to pull back the bulk of their forces to Algeria — a prospect that was now prominent in the anxious minds of the Allied commanders’.

But he found that Arnim — who had already called off the 10th Panzer Division — was unwilling to embark on such a venture. So Rommel sent his proposals to the Comando Supremo — counting on Mussolini’s desire for a ‘victory to bolster up his internal political position’ — while Bayerlein won over the air force commander in Tunisia and gained his support for the plan.

The hours slipped by, and it was not until almost midnight on the 18th that a signal came from Rome authorising the continued attack, appointing Rommel to conduct it, and placing both panzer divisions under him for the purpose. But the order conveyed that the thrust should be made

northward

to Thala and Le Kef, instead of

north-westward

through Tebessa. In Rommel’s view that change was ‘an appalling and incredible piece of short-sightedness’ — for it meant that the combined thrust was ‘far too close to the front and bound to bring us up against the strong enemy reserves’.

So the attack came where Alexander was expecting it, as he had ordered Anderson ‘to concentrate his armour for the defence of Thala’ — although on the erroneous calculation that Rommel would prefer to seek a ‘tactical victory’ than to pursue a less direct strategic aim. This mistaken assumption turned out fortunately for the Allies as things went, thanks to the Comando Supremo — but the Allied forces would have been caught badly off balance had Rommel been allowed to drive the way he wished. For the bulk of the reinforcements, American and British, that had been rushed south were sent to Thala and the Sbiba sector east of it, while Tebessa was meagrely covered by what remained of the U.S. 1st Armored Division.

The main British reinforcement was the 6th Armoured Division. Its armoured component, the 26th Armoured Brigade, was posted at Thala while additional infantry and also the artillery of the now arriving U.S. 9th Infantry Division were brought there to support it. The 1st Guards Brigade, the lorried infantry component of the 6th Armoured Division, was posted to guard the Sbiba gap, due north of Sbeitla, along with three Regimental Combat Teams from the U.S. 1st and 34th Infantry Divisions.