History of the Second World War (9 page)

Read History of the Second World War Online

Authors: Basil Henry Liddell Hart

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Other

In mid-November the Allied Supreme Council had endorsed Gamelin’s Plan ‘D’, a hazardous development — which the British Staff had at first questioned — of an earlier plan. Under Plan ‘D’ the reinforced left wing of the Allied Armies was to rush into Belgium as soon as Hitler started to move, and push as far eastward as possible. That played straight into Hitler’s hands, as it fitted perfectly into his new plan. The farther the Allied left wing pushed into central Belgium the easier it would be for his tank drive through the Ardennes to get round behind it and cut it off.

The outcome was made all the more certain because the Allied High Command employed the bulk of its mobile forces in the advance into Belgium, and left only a thin screen of second-rate divisions to guard the hinge of its advance — facing the exits from the ‘impassable Ardennes’. To make it all the worse, the defences which they had to hold were particularly weak — in the gap between the end of the Maginot Line and the beginning of the British fortified front.

Mr Churchill mentions in his memoirs that anxiety had been felt in British quarters during the autumn about that gap and says: ‘Mr Hore-Belisha, the Secretary of State for War, raised the point in the War Cabinet on several occasions. . . . The Cabinet and our military leaders however were naturally shy of criticising those whose armies were ten times as strong as our own.’* After Hore-Belisha’s departure early in January, following the storm which his criticisms had aroused, there was still less inclination to press the point. There was also a dangerous growth of false confidence, in Britain as well as in France. Churchill declared, in a speech on January 27, that ‘Hitler has lost his best chance’. That comforting assertion was headlined in the newspapers next day. It was the very time when the new plan was fermenting in Hitler’s mind.

* Churchill:

The Second World War,

vol. II, p. 33.

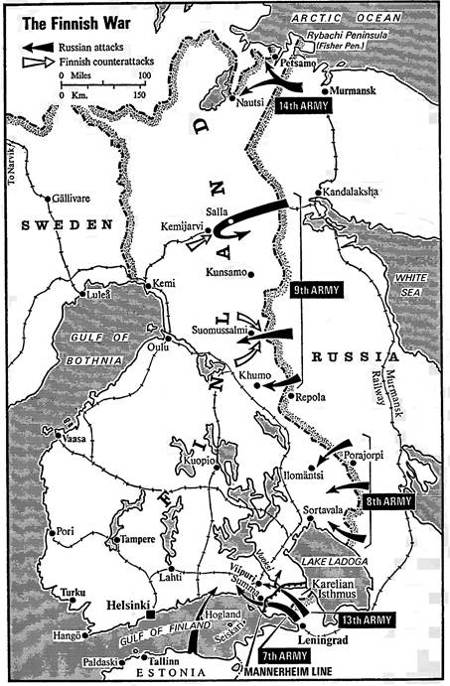

CHAPTER 5 - THE FINNISH WAR

Following the partition of Poland, Stalin was anxious to safeguard Russia’s Baltic flank against a future threat from his temporary colleague, Hitler. Accordingly, the Soviet Government lost no time in securing strategic control of Russia’s old-time buffer-territories in the Baltic. By October 10 it had concluded pacts with Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania which enabled its forces to garrison key-points in those countries. On the 9th conversations began with Finland. On the 14th the Soviet Government formulated its demands. These were defined as having three main purposes.

First, to cover the sea approach to Leningrad, by (a) ‘making it possible to block the Gulf of Finland by artillery from both coasts, to prevent enemy warships or transports entering the Gulf’; (b) ‘making it possible to prevent any enemy gaining access to the islands in the Gulf of Finland situated west and north-west of the entrance to Leningrad’. For this purpose the Finns were asked to cede the islands of Hogland, Seiskari, Lavanskari, Tytarskari, and Loivisto, in exchange for other territories; also to lease the port of Hango for thirty years so that the Russians might there establish a naval base with coastal artillery, capable, in conjunction with the naval base at Paldaski on the opposite coast, of blocking access to the Gulf of Finland.

Second, to provide better cover on the land approach to Leningrad by moving back the Finnish frontier in the Karelian Isthmus, to a line which would be out of heavy artillery range of Leningrad. The re-adjustments of the frontier would still leave intact the main defences on the Mannerheim Line.

Third, to adjust the frontier in the far north ‘in the Petsamo region, where the frontier was badly and artificially drawn’. It was a straight line running through the narrow isthmus of the Rybachi peninsula and cutting off the western end of that peninsula. This re-adjustment was apparently designed to safeguard the sea approach to Murmansk by preventing an enemy establishing himself on the Rybachi peninsula.

In exchange for these re-adjustments of territory the Soviet Union offered to cede to Finland the districts of Repola and Porajorpi — an exchange which, even according to the Finnish White Book, would have given Finland an additional 2,134 square miles in compensation for the cession to Russia of areas totalling 1,066 square miles.

An objective examination of these terms suggests that they were framed on a rational basis, to provide a greater security to Russian territory without serious detriment to the security of Finland. They would, clearly, have hindered the use of Finland as a jumping-off point for any German attack on Russia. But they would not have given Russia any appreciable advantage for an attack on Finland. Indeed, the territory which Russia offered to cede to Finland would have widened Finland’s uncomfortably narrow waistline.

National sentiment, however, made it hard for the Finns to agree to a settlement on these lines. While they expressed willingness to cede all the islands except Hogland, they were adamant about leaving the port of Hango on the mainland — contending that this would be inconsistent with their policy of strict neutrality. The Russians then offered to buy this piece of territory, arguing that such a purchase would be in accord with Finland’s neutrality obligations. The Finns, however, refused this offer. The discussions became acrimonious, the tone of Russian Press comment became threatening, and on November 28 the Soviet Government cancelled the non-aggression treaty of 1932. On the 30th the Russian invasion began.

The original advance ended in a check that astonished the world. A direct push from Leningrad up the Karelian Isthmus came to a halt in the forward layers of the Mannerheim Line. An advance near Lake Ladoga did not make progress. At the other end of the front the Russians cut off the small port of Petsamo on the Arctic Ocean, as a means of blocking the entry of help to Finland by that route.

Two more immediately menacing thrusts were delivered across the waist of Finland. The more northerly thrust penetrated past Salla to Kemijarvi, half way to the Gulf of Bothnia, before it was driven back by the counterattack of a Finnish division which had been switched up by rail from the south. The southerly thrust, past Suomussalmi, was interrupted in turn by a counterstroke, early in January 1940. Circling round the invaders’ flank, the Finns blocked their line of supply and retreat, waited until their troops were exhausted by cold and hunger, then attacked and broke them up.

In the West, sympathy with Finland as a fresh victim of aggression had rapidly developed into enthusiasm at the apparent success of the weak in repulsing the strong. This impression had far-reaching repercussions. It prompted the French and British Governments to consider the despatch of an expeditionary force to this new theatre of war with the object not only of aiding Finland but also of securing the Swedish iron mines at Gallivare from which Germany drew supplies, while establishing a position that threatened Germany’s Baltic flank. Partly because of the objections raised by Norway and Sweden, this project did not materialise before Finland collapsed. France and Britain were thus spared entanglement in war with the U.S.S.R. as well as with Germany at a time when their own powers of defence were perilously weak. But the obvious threat of an Allied move into Scandinavia precipitated Hitler’s decision to forestall it by occupying Norway.

Another effect of Finland’s early successes was that it reinforced the general tendency to underrate the Soviet military strength. This view was epitomised in Winston Churchill’s broadcast assertion of January 20, 1940, that Finland ‘had exposed, for the world to see, the military incapacity of the Red Army’. His misjudgement was to some extent shared by Hitler — with momentous consequences the following year.

More dispassionate examination of the campaign, however, provided better reasons for the ineffectiveness of the original advance. There was no sign of proper preparations to mount a powerful offensive, furnished with large stocks of munitions and equipment from Russia’s vast resources. There were clear signs that the Soviet authorities had been misled by their sources of information about the situation in Finland, and that, instead of reckoning on serious resistance, they imagined that they might have to do no more than back up a rising of the Finnish people against an unpopular Government. The country cramped an invader at every turn, being full of natural obstacles that narrowed the avenues of approach and helped the defence. Between Lake Ladoga and the Arctic Ocean the frontier appeared very wide on the map but in reality was a tangle of lakes and forests, ideal for laying traps as well as for stubborn resistance. Moreover, on the Soviet side of the frontier the rail communications consisted of the solitary line from Leningrad to Murmansk, which in its 800-mile stretch had only one branch leading to the Finnish frontier. This limitation was reflected in the fact that the ‘waistline’ thrusts which sounded so formidable in the highly coloured reports from Finland were made with only three divisions apiece, while four were employed in the outflanking manoeuvre north of Ladoga.

Much the best approach to Finland was through the Karelian Isthmus between Lake Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland, but this was blocked by the Mannerheim Line and the Finns’ six active divisions, which were concentrated there at the outset. The Russian thrusts farther north, though they fared badly, served the purpose of drawing part of the Finnish reserves thither while thorough preparations were being made, and fourteen divisions brought up, for a serious attack on the Mannerheim Line. This was launched on February 1, under the direction of General Meretskov. Its weight was concentrated on a ten-mile sector near Summa, which was pounded by a tremendous artillery bombardment. As the fortifications were pulverised, tanks and sledge-carried infantry advanced to occupy the ground, while the Soviet air force broke up attempted countermoves. After little more than a fortnight of this methodical process a breach was made through the whole depth of the Mannerheim Line. The attackers then wheeled outward to corner Finnish forces on either flank, before pushing on to Viipuri (Viborg). A wider flanking operation was carried out across the frozen Gulf of Finland by troops who advanced from the ice-bound island of Hogland and landed well in the rear of Viipuri. Although an obstinate defence was still maintained for several weeks in front of Viipuri, Finland’s limited forces had been worn down in the effort to hold the Karelian Isthmus. Once a passage was forced, and their communications menaced, eventual collapse was certain. Capitulation was the only way in which it could be averted, since the proffered Franco-British expeditionary force had not arrived, though almost ready to sail.

On March 6, 1940, the Finnish Government sent a delegation to negotiate peace. Beyond the earlier Soviet conditions, Finland was now asked to cede areas in the communes of Salla and Kunsamo, the whole of the Karelian Isthmus, including Viipari, and also the Finnish part of the Fisher Peninsula. They were also asked to build a railroad from Kemijarvi to the frontier (which was not yet established) to link up to the Russian spur. On March 13 it was announced that the Soviet terms had been accepted.

In the radically changed circumstances, particularly after the disastrous collapse in the Summa sector of the Mannerheim Line on February 12, the new Soviet terms were remarkably moderate. But Field-Marshal Mannerheim, who was more of a realist than most statesmen, and rightly dubious about the pressing Franco-British offers of help, urged acceptance of the Soviet terms. In raising his requirements so little, Stalin too showed statesmanship, while evidently anxious to be quit of a commitment which had occupied more than a million of Russia’s troops, as well as a high proportion of her tanks and aircraft, at a time when the crucial spring of 1940 was looming near.

Whereas conditions in Poland were more favourable to a Blitzkrieg offensive than anywhere else in Europe, Finland offered a most unsuitable theatre for such a performance, especially at the time of the year when the invasion was staged.

The geographical encirclement of the Polish frontier was intensified by the ampleness of the German communications and the scarcity of the Polish. The open nature of the country offered scope for the thrusts of mechanised forces that was guaranteed by the dry September weather. The Polish Army was even more wedded to the offensive tradition than most armies, and thus all the weaker in utilising its sparse means of defensive action.

In Finland, by contrast, the defender profited by having a much better system of internal communications, both rail and road, than the attacker possessed on his side of the frontier. The Finns had several lines of railway parallel to the frontier for the rapid lateral switching of their reserves; the Russians had only the solitary line from Leningrad to Murmansk, with its one branch to the Finnish frontier. Elsewhere, the Russians would have to advance anything from 50 to 150 miles from the railway before crossing the frontier, and considerably farther before they could threaten any point of strategic importance. That advance, moreover, had to be made through a country of lakes and forests, and over poor roads that were now deep in snow.