H.M.S. Unseen (35 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

Bill laughed. But he was thoughtful. “And what gave rise to this sudden desire to exhume the Israeli commander?”

“Ah, that’s another story,” replied the admiral. “I’ll tell you at dinner. Come on, let’s go in and have some tea…we’ve walked far enough for one day.”

“Do you really think he’s still alive, Daddy?”

“Quite frankly, yes I do.”

“Try to remember, darling,” said Bill soothingly. “Should he call, don’t forget to let us know.”

Dinner that night was a re-creation of the feast Bill had enjoyed when first he had come to visit the admiral back in 2002, the time when he had first met Mrs. Laura Anderson. There was a magnificent poached salmon, with mayonnaise, potatoes, and peas. A bottle of elegant white Burgundy from Mersault and a superb bottle of Lynch Bages 1990 were set in the middle of the table. Bill remembered two things about his first dinner at the MacLeans—one that the admiral never served a first course with salmon, because he believed everyone would much rather have “another bit of fish if they were still hungry.” Two, the admiral preferred to drink Bordeaux with salmon, as did Laura, which left Lady MacLean to deal with the Mersault.

Of the many other differences between the previous time and this one, the most striking was the lack of a view. In that hot July when his heart raced at the very sight of Laura, he had been able to see right down the loch while they dined, and he recalled Sir Iain pointing out through the window the little village of Strachur over on the Cowal Peninsula,

On this occasion it was just as charming but different. There was a glowing log fire in the 50-foot-long dining room, and the big patterned brocade curtains were drawn. Lights were switched on above the six paintings that hung from the high walls, three ancestors, one nineteenth-century racehorse, a stag, probably at bay, and a pack of hounds in full flight. Otherwise, the only light in the room came from the eight lighted candles, set in obviously Georgian silver holders, which Bill thought probably came with the house.

As before, he sat next to Laura, facing Annie MacLean, the two girls having had an early supper in order to watch television in Laura’s old nursery.

The salmon was as good as the last time, when it was the best Bill had ever tasted. The Lynch Bages was perfect, and the admiral was amusing, recounting tall stories about Arnold Morgan’s visit several months ago.

“What precisely did he come here for?” asked Bill.

“Well, I think he wanted to get away for a week or so with that extremely attractive lady he plans to marry.”

“Kathy? Yes, she is very beautiful, isn’t she?”

“Absolutely,” said Sir Iain. “I told him she was probably a bit too good for him really. And he took it very well, for him.”

“But what else, Iain? Tell me more.”

“Well, Bill, I suppose you, if anyone, is entitled to know this. And so indeed is your wife. I have been wondering whether to break this to you gently or just to come straight out with it. And I’ve decided on the latter course. Arnold Morgan and I think that Ben Adnam has stolen, and now commands, the missing Royal Navy submarine HMS

Unseen,

and that he has been sitting in the middle of the Atlantic, underwater, banging out jet airliners, including Concorde, Starstriker

,

and

Air Force Three.”

As showstoppers go, that one went. Laura choked on her Lynch Bages, and Bill dropped his fork on the table with a clatter.

But he recovered, quickly. “Oh, nothing serious,” he said. “I was thinking it might be something important.”

“Oh, no,” said the admiral, “very routine. Just the sort of thing he might do, don’t you think?”

“Well, assuming he managed to jump off that Egyptian funeral pyre, I’d say most definitely. Right up his alley. Any evidence, or are you and Arnold going in for thriller writing?”

“Actually, there isn’t much evidence, except circumstantial. But there’s a lot of it, and, very curiously, Arnold and I stacked it up quite separately, on different sides of the Atlantic, and arrived at precisely the same conclusion.”

“Might I ask when Arnold arrived here?”

“Yes. Last May. A few weeks after

Unseen

went missing. He came here with a real bee in his bonnet about it. And his reasons, as you would expect, were pretty good. He considered first that the submarine had not been found by the Royal Navy, despite the use of God knows how many ships, all the most modern sonar, and underwater diving equipment in a relatively narrow, shallow section of the English Channel. It was obviously not there. He thus reasoned that it had left its exercise area, and that it had been deliberately driven out of that area by someone else. Not, he decided, by the British lieutenant commander who was in charge.

“Therefore, he considered the ship had been either hijacked or stolen, and he went for the second option.

Unseen

sent all the right signals back, as soon as she left Plymouth; therefore, her CO knew what they were and he knew how to send them. Ben Adnam? I taught him all that; I even taught him how to drive an Upholder

-

Class boat, which

Unseen

is.”

“Hmmmm,” said Bill. “And then…?”

“Well, she vanishes and is never heard from again. But then the Concorde falls out of the sky, for no reason whatsoever. The most brilliantly maintained aircraft on the North Atlantic suddenly vanishes without a word. Then, a matter of days later, Starstriker falls out of the sky on her maiden voyage. A brand-new, tried and tested prototype that Boeing swear by, an aircraft that’s been under guard for weeks, no passengers, just crew, falls straight into the Atlantic without a word. Same place, 30 West, right on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the very best place in all the ocean to hide a submarine.

“And then

Air Force Three.

Virtually new. Flown by one of the best pilots in the United States Air Force. Vanishes, and I hear on the grapevine, there were smoke trails spotted, of the kind that might fit a missile.”

“One major point, Iain.

Unseen

has no weapon that would fire such a missile. Neither does any other submarine in the world. Such a system would have to be custom-made and fitted…I think.”

“Well, Bill, I think Arnold believes the Iraqis found a way, and did fit such a system. I intended to ask you what you thought might be feasible.”

“I suppose one of those advanced Russian SAMs might do it…maybe the Grumble Rif. It’d have to be radar-guided. Heat-seeking wouldn’t do it, because the supersonics would be going too fast. Come to think of it, you could probably adapt the submarine’s regular radar just to a part of the system, the launcher and the missiles. Then you could catch the aircraft coming in…just in the normal way. Then send the bird away right off the casing, to the correct altitude, and let the missile’s own radar in the nose cone do the rest. Couldn’t miss if it was done right.”

“One problem, Bill. I wanted to ask you. If it was Iraq, and we know Adnam is an Iraqi,

where?

That’s what’s exercising Arnold and me,

where

could they have made the conversion. They have no submarine facilities.”

“I don’t see that as a major problem, because I think such a system could be bolted onto the deck. You could get most of the high-tech work completed inside the submarine. If you could hide her for a short while, alongside a submarine workshop ship…well, I’m saying you might get it done without even going into a dry dock, so long as there was a crane on board. Remember, Adnam got ahold of a submarine before when he needed it. I guess he could have done it again.

“No, I think the biggest problem for Adnam would be getting a crew. There are no submariners in the Iraqi Navy. And there would be no way to train them. And he surely could not have persuaded an entire crew of Brazilians to go along with the scheme. Did Admiral Morgan have any ideas on that? Or did he just assume Adnam found a way, like he did with the Russian Kilo?”

“He didn’t mention any of that. I thought perhaps he might know something he was not prepared to share with me. Anyway, Bill, that more or less brings you into line with our thinking. But the problem of finding it is very tough. And there have been a few developments around here that I’ve been pondering, probably stupidly, just because I’ve got a bit too much time on my hands these days. Let’s just finish our coffee, then we’ll go over to the study and have a glass of port, and I’ll show you a few things…Laura, you wouldn’t pop over and put a couple of logs on the fire in there, would you?”

“Only if I can come over with you and have some of that port,” she replied. “How about you, mum?”

“Oh, I won’t, dear. I’m off to bed. It’s been rather a long day, so don’t keep your father up half the night.”

“No danger of that…Bill and I would like to be a-l-o-o-o-o-ne in the room where we first fell in love…I’ll send Daddy packing, don’t you worry.”

Everyone laughed, and they helped take the cups and dishes to the kitchen before crossing the hall to the book-lined study, in which Laura was blasting the fire with bellows. Then she thoughtfully poured three glasses of Taylor’s ’78 and sat in the left-hand chair, leaving Bill and her father to sit closer and study an atlas he had obviously been using recently.

Sure enough, he handed the heavy book to the Kansan, holding it open to a map of the eastern side of the North Atlantic. “You will see on there, I have made a succession of crosses placed in circles…well, the one on the far left is the place where the two supersonic jets went down. The next one, more easterly, is where you lost the Vice President in

Air Force Three.

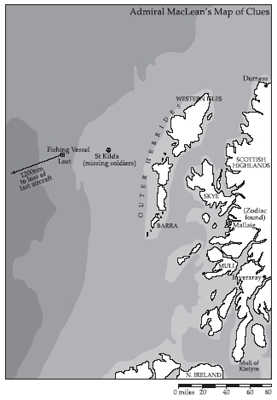

The next two are more recent…very up-to-date. You see the one about 35 miles west of St. Kilda?”

“Got it.”

“Well, we have reports in the Scottish papers this month of a mysterious incident…a fishing boat just vanished somewhere out near there. And there were a few rather baffling circumstances attached to it. My next cross is exactly on the island of St. Kilda, where, a couple of days later, two trained British soldiers, an officer and an experienced corporal, just vanished, and they haven’t found ’em yet.

“My fifth cross is in the harbor of Mallaig, where there may be yet another mystery. The tender from the lost fishing boat, a 15-foot Zodiac, suddenly turns up on someone’s mooring a couple of days later, and everyone is saying the chap who discovered it, a lobsterman, was a habitual drunk and ought not to be listened to. He says the boat had been on his mooring just a few hours. The police say in the newspapers, it must have been on the mooring for days.

“Bill, quite frankly, if you are a fisherman, I don’t care how pissed you are, you’d know if someone had parked a bloody great rubber boat on your mooring four days ago, or last night. I think the lobsterman ought to be listened to.”

“Mmmmmm,” said Bill, studying the map intently.

“And now I’m going to leave you with this thought…follow my crosses…look at the dates…see how they move in a steady easterly direction…a chain of circumstances…leading to what? Ben Adnam? I wonder. Let’s regroup in the morning…breakfast 0900 I think. Good night, you two…oh, and Bill have a look at the little book there…the one about St. Kilda. I think you’ll find it interesting.”

Laura walked across the room and removed the atlas from Bill’s lap, folded it, and placed it, with exaggerated firmness, on a shelf. She then took from a side table a CD, walked over to the player, and turned it on.

“

Rigoletto,”

he said.

“The first one we ever listened to together, my darling,” she whispered. “Right here in this room, nearly four years ago…Placido Domingo as the duke, Ileana Cortrubas as Gilda.”

And as the rhapsodic sounds of Verdi’s overture rang out, dominated by the glorious violins of the Vienna Philharmonic, Laura walked to her husband, sat on his lap, and hugged him as she always did, as if she would never let him go.

“I love you,” she said. “And it happened in this room. When I had known you for about three hours. I’ve never doubted it, and I would change nothing.”

“Nor me,” said Bill.

“Nor I,” she corrected, laughing at his inability to deal with “me” and “I.” And then she kissed him as she always did, softly, with her hands in his hair, and her touch electrified him as ever.

“Same bedroom tonight,” she said. “How lovely. How unbearably romantic.”

Neither of them knew that beyond the deep red curtains of the study, out under the tall hedges beside the road near the main gate, was parked a metallic blue Audi A8, its driver finding an unbalanced peace just in being there.

March 31, 2006.

B

Y 0100 THE DOWNSTAIRS LIGHTS WERE OUT IN THE

locked, silent MacLean household. The three Labradors were asleep in the big kitchen near the Aga, but they had, at the insistence of the admiral, the complete run of the house throughout the night hours, should an intruder decide to press his luck. However, this had never happened, since most burglars were aware that the average Labrador is a bit of a Jekyll and Hyde, once dark has fallen and a house is quiet. From a cheerful, boisterous companion, he turns into a suspicious, growling watchdog, likely to go berserk at the slightest sound. That huge neck of his powers jaws that can snap a lamb bone in two. The reason the British police do not use Labradors in confrontational situations is their instinct to go straight for a man’s throat.

Ben Adnam was unaware of these canine subtleties, and at 0115 he stepped out of his car and walked softly down the drive toward the house. He did so for reasons that were beyond him. He just wanted to be close to the building where once he had been near to Laura. The trouble was, the black, burly Fergus was unaware of his motives, and, with ears that could hear a shot pheasant hit the ground at 200 yards, he heard a footfall on the gravel drive. He came off his bean bag like a tiger, barking at the top of his lungs, racing toward the front door, pursued now by the even bigger Muffin, and Mr. Bumble.

The noise was outrageous. Upstairs, the admiral awakened and walked out into the corridor, where Bill was already standing in his dressing gown, with all the downstairs hall lights on.

“What’s the matter with them?” he asked.

“I don’t know, Iain, but when dogs react like that in the middle of the night it’s always because they heard something.”

And even as they spoke, they heard the unmistakable sound of a car pulling away, heading up toward the village of Inverary, fast.

“Probably someone was lost,” said the admiral. “It’s pretty dark out there.”

The dogs were quiet now, and Sir Iain turned out the lights. “See you in the morning Bill, 0900.”

“Yessir,” said Bill, against house protocol.

Commander Adnam shot through Inverary at almost 70 mph his headlights on full beam. He might not have had much success at beating his all-time record to St. Catherine’s and back. But he set some kind of a mark for the Scottish all-comers Inverary–Creggans Inn run. Right around the north end of the loch, pedal to the floor. He used his key to slip in the side door and went immediately up to his room. And there he lay exhausted on his bed, wondering exactly who was at home in his former Teacher’s house, and where Laura was.

Would he ever see her again? And what had he been doing, lurking in the night shadows, like some burglar? He did not know. Except there was nowhere else where he could connect with anyone, even in his mind. It was as if the aura of the MacLeans, a family that once had almost liked him, had created a roomful of memories. And to sit in his cold car outside the house was to sit in that room. The alternative was so lonely, so frighteningly isolated, that he did not believe he could face it for much longer.

He knew one thing, however. For the first time in his life, he was in danger of losing his grip. Because there was nothing for him to do. He was friendless, stateless, and certainly homeless. And his ungrasped straw was Laura.

Ben did not sleep at all that night. Partly because he was afraid to do so, because of the nightmares. But mostly because he knew he had to move and seek out a direction. The problem was he could not even make a phone call, because there was no one he could call. One false move, and he would be arrested and possibly deported to the United States, where he was undoubtedly Public Enemy Number One. If they nailed him, they would not, he knew, bother with murder or life imprisonment. He would face a charge equivalent to treason against the state, and that, he guessed, meant the chair.

He drank just coffee at breakfast, in sharp contrast to the splendor of the spread that was prepared at the MacLeans. The admiral loved fish for breakfast, so long as it was served after 0900, and Angus had prepared both kippers and poached haddock, for two, since none of the female members of the household had yet made an appearance.

Bill had never had fish for breakfast, but he entered into the spirit and tasted his first kippers, ended up having two pairs of the rich, smoked Scottish herrings.

Over China tea, and toast with locally made chunky marmalade, he and the admiral settled down to chat about the Great Theory. The atlas was already open on the table. “Well, Bill,” said Sir Iain, “what did you come up with?”

“Not much really. I was tired as hell, and Laura wanted to play some opera for sentimental reasons. By midnight I thought

Rigoletto

was driving HMS

Unseen.”

The admiral chuckled, and produced some newspaper clippings. “Here,” he said, “read this one…it’s got the stuff in it from the lobsterman, the stuff they have all, apparently, dismissed as unreliable. I’d be glad if you’d read it.”

Bill did so slowly. “Well, Mr. MacInnes was pretty definite, wasn’t he? I mean about the Zodiac suddenly showing up in the small hours of the morning. And he was also pretty definite about the new guy on the fishing boat, the one wearing the military jacket.”

“Wasn’t he, though? Very definite. And I can understand why. That chap has lived all his life in Mallaig, where his father was also a fisherman. The sight of that harbor is unchanging.

Anything

slightly out of the ordinary would register, even to a man who’s had a few drinks. He’s probably seen Gregor Mackay’s boat pull out of that harbor a thousand times…but on that particular day he noticed something different, a new face…strange clothes. A man standing on the stern by the Zodiac, where MacInnes had never seen anyone before. To him, that would be a major departure from the norm. As if you reported to Boomer Dunning’s

Columbia

and found a Zulu warrior at the periscope.”

Bill laughed, but he was very serious. And he interjected, “Like seeing a sheep on my land. We’ve never raised them. Just cattle.”

“Exactly so, Bill. That man, even through the alcohol, remembered. If I were the investigator, I’d regard the drinks as a plus, not a minus.”

“I think I would, too, Iain. So what you’re saying is that someone got off the fishing boat, in the Zodiac, and drove it all the way back to Mallaig. Christ, it’s gotta be, what? A hundred and sixty miles?”

“At least…more like 175, I’d say.”

“It couldn’t carry that much gas, could it?”

“Easily. If it had four of those four-and-half-gallon jerry cans. Then it might.”

“Well, let’s assume, it did. What does this have to do with the man commanding the rogue submarine?”

“Only that someone may have got off the rogue submarine.”

“Onto Gregor Mackay’s kipper ship?”

“Possibly.”

“You think he was out there recruiting?”

Sir Iain laughed loudly this time. “Bill, I love that American sense of humor…but that’s not really what I meant. I meant maybe Gregor’s boat had been hired to go out and

take

someone off the rogue submarine.”

“But who could have hired it? The Iraqi Embassy?”

“No,” replied the admiral. “But how about the foreign-looking laddie in the Navy jacket standing by the Zodiac.”

“Jesus, I’ve been so busy making jokes, I never really thought about that.”

“Well, son-in-law. Think.”

“Right. I’ll do it. One question. How far from the place

Air Force Three

went down was the

Flower of Scotland’s

last-known position?”

“I’ve calculated it, Bill. The VP crashed at 53 North, 20 West. The

Flower

’s last known was around 57.49 North, 9.40 West, about 490 miles. That’s the distance between the final hit on

Air Force Three

and the place where the

Flower of Scotland

vanished.”

“How about timing?”

“The Boeing was lost around 1300 GMT on Sunday, February26. The harbormaster at Mallaig lost contact with Captain Mackay on the night of March 1.”

“So the submarine had six days to get there.”

“It would have done, my boy, if February had more than twenty-eight days in this non–leap year.”

“Christ, I’d forgotten about that. So it had only a little over three and a half days?”

“Correct.”

“You got a calculation on that, sir?”

“Uh-huh. Four hundred ninety divided by three and a half is 140 miles a day. Divide that by 24, and you have a nice quiet little running speed of 5.8 knots. Just about reasonable for a submarine creeping away from a crime to a meeting point, wouldn’t you say?”

“Just. But then what? Ben gets off, pinches the Zodiac, and somehow sinks the fishing boat? I can’t buy that. If Captain Mackay had come all the way out to meet him, why didn’t Ben just travel to Mallaig with the boat?”

“Well, I agree, Bill. It’s all a bit far-fetched. But in the middle of it all, we do have one incontrovertible fact—the fishing boat did vanish. I suppose Ben, or whoever it was, could have shot the crew dead, left in the Zodiac, and lobbed a hand grenade on board as he went. But that’s unreal, reckless thinking. Not at all like him. Too noisy. Too likely to be discovered. What if someone heard the explosion? He could not afford that.”

“And how about the gas for the outboard? There’s no chance there was enough for 175 miles. And the trawler’s diesel fuel would not work in an outboard. Which puts Ben in the middle of the Atlantic in the middle of the night with no fuel. Don’t like it, sir. Doesn’t stack.”

“Not quite. I agree. And the disappearance of the trawler is something I don’t really have an answer for. But Ben would know how to sink a boat…if he was prepared to kill the captain and the two crewmen.”

“Only to be stranded himself, Iain. Stranded absolutely nowhere. And no way to get anywhere.”

“Ah, but Bill. There is something you have forgotten. Someone got somewhere. Someone got the Zodiac back to port, right back to Ewan MacInnes’s mooring, on the morning of March 3. That’s when he says it arrived. You see, I believe him.”

“All true. But how? They don’t usually run on air.”

“No. They don’t. But it would be nice to ask the two missing soldiers, don’t you think? St. Kilda is only 35 miles from the

Flower of Scotland

’s last known. Ben could have made it to there.”

“Jesus, sir. So he could. I wonder if they’ve noticed missing gas, or missing gas cans.”

“I imagine they’re too busy looking for missing soldiers…but it’s food for thought, don’t you think?”

“It sure as hell is.”

“What I can’t work out, is what happened to the fishing boat? But I can work out that Ben Adnam, having planned his evacuation from the submarine, might have been the man in that Zodiac, for whatever reason. So he goes to the military base at St. Kilda, takes out the two soldiers, steals as much gas as he needs, and arrives in Mallaig a couple of days later, on the morning of March 3, when Ewan MacInnes noticed Gregor Mackay’s tender on his mooring.”

“Admiral, for a story with as many holes in it as that one…you make out a very good case. Tell me your conclusion.”

“I think Ben Adnam was in Scotland. I actually think he might still be here…and what worries me is what he might be planning. I mean it would not be beyond him to take a shot at a Trident submarine. I just don’t know, but Arnold Morgan and I both think he stole HMS

Unseen.

And God knows what he might do next.”

“Be kinda interesting if he stole a Trident and blew up half the world, wouldn’t it?”

“Extremely. The trouble is there are really only three people in this world who understand the man and his capabilities. I, who taught him. You, who caught him. And Arnold, who’s paranoid about him.”

“Mmmmmm…one thing, Iain…picture this yourself. You’re in a 15-foot boat climbing through the Atlantic swell. It’s freezing cold, you’re all alone in the pitch-dark heading for an uninhabited rock called St. Kilda. According to your little book the place is surrounded by huge black cliffs and is just about unapproachable in winter. How the hell could anyone manage a safe landing under those circumstances?

“You’d get swept onto the rocks and drown and no one would ever know.”

“Not Ben. He’s been there before. At least he’s been close enough to have a good look at Village Bay in the southeast, right from the fin of a submarine.”

“He has? How do you know that?”

“I was there.”

On Monday morning, April 3, Ben Adnam checked out of the Creggans Inn and drove to Helensburgh. He paid the second cash installment on the car and asked if he might keep it another week. He’d pay £150 extra if it was less than a week, £300 if it was more. “As long as you like, sir. Just keep us informed if you want it more than two weeks.”

Ben picked up more cash at the Royal Bank of Scotland and requested they provide him with two credit cards, a VISA and an RBS bank card, plus a couple of checkbooks. He expected, he said, to be going on a journey, and he would be wiring £50,000 into his account that same day.

The bank was more than happy to oblige an excellent, if frequently absent, customer like Mr. Arnold, and agreed that his business mail would be held there at the Helensburgh branch until further notice. The bank would deduct credit-card bills from his account automatically. He could pick up both cards in a few days.

The commander then set off for Edinburgh, a drive of 70 miles, straight through Glasgow and on to Scotland’s capital city along the M8 motorway. He located and checked into the Balmoral Hotel, at the eastern end of Prince’s Street, right above the Waverley Railway Station. And, in the absence of a credit card, left a deposit of £500 with the receptionist.

He checked into his room and immediately left the hotel, walking swiftly up The Bridges to the nearby offices of

The Scotsman,

with its new computerized reference room in which, for a fee, readers can sit in a small cubicle and pull up on the screen clips and pictures from any news event that the newspaper has covered. There is a further charge for printouts and copies, but the place is a fountain of information, and the Iraqi terrorist wished to bring himself up-to-date with world events that had taken place in the long months he had been at the helm of HMS

Unseen:

particularly those events in which he had personally been involved.