Hollow City (11 page)

Authors: Ransom Riggs

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Horror & Ghost Stories, #General

When I was done I belched and wiped my mouth and looked up to see all the animals looking back, watching us eagerly, their faces so alive with intelligence that I went a little numb and had to fight an overwhelming sensation that I was dreaming.

Millard was eating next to me, and I turned to him and asked, “Before this, had you ever heard of peculiar animals?”

“Only in children’s stories,” he said through a mouthful of bread. “How strange, then, that it was one such story that led us to them.”

Only Olive seemed unfazed by it all, perhaps because she was still so young—or part of her was, anyway—and the distance between stories and real life did not yet seem so great. “Where are the other animals?” she asked Addison. “In Cuthbert’s tale there were stilt-legged grimbears and two-headed lynxes.”

And just like that, the animals’ jubilant mood wilted. Grunt hid his face in his big hands and Deirdre let out a neighing groan. “Don’t

ask, don’t ask,” she said, hanging her long head. But it was too late.

“These children helped us,” Addison said. “They deserve to hear our sad story, if they wish.”

“If you don’t mind telling us,” said Emma.

“I love sad stories,” said Enoch. “Especially ones where princesses get eaten by dragons and everyone dies in the end.”

Addison cleared his throat. “In our case, it’s more that the dragon got eaten by the princess,” he said. “It’s been a rough few years for the likes of us, and it was a rough few centuries prior to that.” The dog paced back and forth, his voice taking on a preacherly kind of grandness. “Once upon a time, this world was full of peculiar animals. In the

Aldinn

days, there were more peculiar animals on Earth than there were peculiar folk. We came in every shape and size you could imagine: whales that could fly like birds, worms as big as houses, dogs twice as intelligent as I am, if you can believe it. Some had kingdoms all their own, ruled over by animal leaders.” A spark moved behind the dog’s eyes, barely detectable—as if he were old enough to remember the world in such a state—and then he sighed deeply, the spark snuffed, and continued. “But our numbers are not a fraction of what they were. We have fallen into near extinction. Do any of you know what became of the peculiar animals that once roamed the world?”

We chewed silently, ashamed that we didn’t.

“Right, then,” he said. “Come with me and I’ll show you.” And he trotted out into the sun and looked back, waiting for us to follow.

“Please, Addie,” said the emu-raffe. “Not now—our guests are eating!”

“They asked, and now I’m telling them,” said Addison. “Their bread will still be here in a few minutes!”

Reluctantly, we put down our food and followed the dog. Fiona stayed behind to watch Claire, who was still sleeping, and with Grunt and the emu-raffe loping after us, we crossed the plateau to

the little patch of woods that grew at the far edge. A gravel path wound through the trees, and we crunched along it toward a clearing. Just before we reached it, Addison said, “May I introduce you to the finest peculiar animals who ever lived!” and the trees parted to reveal a small graveyard filled with neat rows of white headstones.

“Oh,

no

,” I heard Bronwyn say.

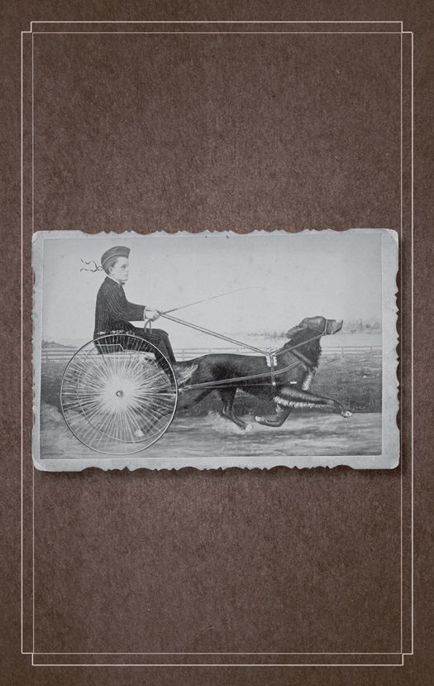

“There are probably more peculiar animals buried here than are currently alive in all of Europe,” Addison said, moving through the graves to reach one in particular, which he leaned on with his forepaws. “This one’s name was Pompey. She was a fine dog, and could heal wounds with a few licks of her tongue. A wonder to behold! And yet

this

is how she was treated.” Addison clicked his tongue and Grunt scurried forward with a little book in his hands, which he thrust into mine. It was a photo album, opened to a picture of a dog that had been harnessed, like a mule or a horse, to a little wagon. “She was enslaved by carnival folk,” Addison said, “forced to pull fat, spoiled children like some common beast of burden—whipped, even, with riding crops!” His eyes burned with anger. “By the time Miss Wren rescued her, Pompey was so depressed she was nearly dead from it. She lingered on for only a few weeks after she arrived, then was interred here.”

I passed the book around. Everyone who saw the photo sighed or shook their head or muttered bitterly to themselves.

Addison crossed to another grave. “Grander still was Ca’ab Magda,” he said, “an eighteen-tusked wildebeest who roamed the loops of Outer Mongolia. She was terrifying! The ground thundered under her hooves when she ran! They say she even marched over the Alps with Hannibal’s army in 218

BC

. Then, some years ago, a hunter shot her.”

Grunt showed us a picture of an older woman who looked like she’d just gotten back from an African safari, seated in a bizarre chair made of horns.

“I don’t understand,” said Emma, peering at the photo. “Where’s

Ca’ab Magda?”

“Being sat upon,” said Addison. “The hunter fashioned her horns into a chair.”

Emma nearly dropped the album. “That’s disgusting!”

“If that’s her,” said Enoch, tapping the photo, “then what’s buried here?”

“The chair,” said Addison. “What a pitiful waste of a peculiar life.”

“This burying ground is filled with stories like Magda’s,” Addison said. “Miss Wren meant this menagerie to be an ark, but gradually it’s become a tomb.”

“Like all our loops,” said Enoch. “Like peculiardom itself. A failed experiment.”

“ ‘This place is dying,’ Miss Wren often said.” Addison’s voice rose in imitation of her. “ ‘And I am nothing but the overseer of its long funeral!’ ”

Addison’s eyes glistened, remembering her, but just as quickly went hard again. “She was very theatrical.”

“Please don’t refer to our ymbryne in the past tense,” Deirdre said.

“Is,” he said. “Sorry.

Is

.”

“They hunted you,” said Emma, her voice wavering with emotion. “Stuffed you and put you in zoos.”

“Just like the hunters did in Cuthbert’s story,” said Olive.

“Yes,” said Addison. “Some truths are expressed best in the form of myth.”

“But there was no Cuthbert,” said Olive, beginning to understand. “No giant. Just a bird.”

“A very

special

bird,” said Deirdre.

“You’re worried about her,” I said.

“Of course we are,” said Addison. “To my knowledge, Miss Wren is the only remaining uncaptured ymbryne. When she heard that her kidnapped sisters had been spirited away to London, she flew off to render assistance without a moment’s thought for her own safety.”

“Nor ours,” Deirdre muttered.

“London?” said Emma. “Are you sure that’s where the kidnapped ymbrynes were taken?”

“Absolutely certain,” the dog replied. “Miss Wren has spies in the city—a certain flock of peculiar pigeons who watch everything and report back to her. Recently, several came to us in a state of terrible

distress. They had it on good information that the ymbrynes were—and still are—being held in the punishment loops.”

Several of the children gasped, but I had no idea what the dog meant. “What’s a punishment loop?” I asked.

“They were designed to hold captured wights, hardened criminals, and the dangerously insane,” Millard explained. “They’re nothing like the loops we know. Nasty, nasty places.”

“And now it is the wights, and undoubtedly their hollows, who are guarding them,” said Addison.

“Good God!” exclaimed Horace. “Then it’s worse than we feared!”

“Are you joking?” said Enoch. “This is

precisely

the sort of thing I feared!”

“Whatever nefarious end the wights are seeking,” Addison said, “it’s clear that they need all the ymbrynes to accomplish it. Now only Miss Wren is left … brave, foolhardy Miss Wren … and who knows for how long!” Then he whimpered the way some dogs do during thunderstorms, tucking his ears back and lowering his head.

* * *

We went back to the shade tree and finished our meals, and when we were stuffed and couldn’t eat another bite, Bronwyn turned to Addison and said, “You know, Mister Dog, everything’s not quite as dire as you say.” Then she looked at Emma and raised her eyebrows, and this time Emma nodded.

“Is that so,” Addison replied.

“Yes, it is. In fact, I have something right here that may just cheer you up.”

“I rather doubt that,” the dog muttered, but he lifted his head from his paws to see what it was anyway.

Bronwyn opened her coat and said, “I’d like you to meet the

second-to-last uncaptured ymbryne, Miss Alma Peregrine.” The bird poked her head out into the sunlight and blinked.

Now it was the animals’ turn to be amazed. Deirdre gasped and Grunt squealed and clapped his hands and the chickens flapped their useless wings.

“But we heard your loop was raided!” Addison said. “Your ymbryne stolen!”

“She was,” Emma said proudly, “but we stole her back!”

“In that case,” said Addison, bowing to Miss Peregrine, “it is a most extraordinary pleasure, madam. I am your servant. Should you require a place to change, I’ll happily show you to Miss Wren’s private quarters.”

“She

can’t

change,” said Bronwyn.

“What’s that?” said Addison. “Is she shy?”

“No,” said Bronwyn. “She’s stuck.”

The pipe dropped from Addison’s mouth. “Oh, no,” he said quietly. “Are you quite certain?”

“She’s been like this for two days now,” said Emma. “I think if she could change back, she would’ve done it by now.”

Addison shook the glasses from his face and peered at the bird, his eyes wide with concern. “May I examine her?” he asked.

“He’s a regular Doctor Dolittle,” said the emu-raffe. “Addie treats us all when we’re sick.”

Bronwyn lifted Miss Peregrine out of her coat and set the bird on the ground. “Just be careful of her hurt wing,” she said.

“Of course,” said Addison. He began by making a slow circle around the bird, studying her from every angle. Then he sniffed her head and wings with his big, wet nose. “Tell me what happened to her,” he said finally, “and when, and how. Tell me all of it.”

Emma recounted the whole story: how Miss Peregrine was kidnapped by Golan, how she nearly drowned in her cage in the ocean, how we’d rescued her from a submarine piloted by wights. The animals listened, rapt. When we’d finished, the dog took a moment

to gather his thoughts, then delivered his diagnosis: “She’s been poisoned. I’m certain of it. Dosed with something that’s keeping her in bird form artificially.”

“Really?” said Emma. “How do you know?”

“To kidnap and transport ymbrynes is a dangerous business when they’re in human form and can perform their time-stopping tricks. As birds, however, their powers are very limited. This way, your mistress is compact, easily hidden … much less of a threat.” He looked at Miss Peregrine. “Did the wight who took you spray you with anything?” he asked her. “A liquid or a gas?”

Miss Peregrine bobbed her head in the air—what seemed to be a nod.

Bronwyn gasped. “Oh, miss, I’m so awfully sorry. We had no idea.”

I felt a stab of guilt.

I

had led the wights to the island.

I

was the reason this had happened to Miss Peregrine.

I

had caused the peculiar children to lose their home, at least partly. The shame of it lodged like a stone in my throat.