Hollow City (39 page)

Authors: Ransom Riggs

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Horror & Ghost Stories, #General

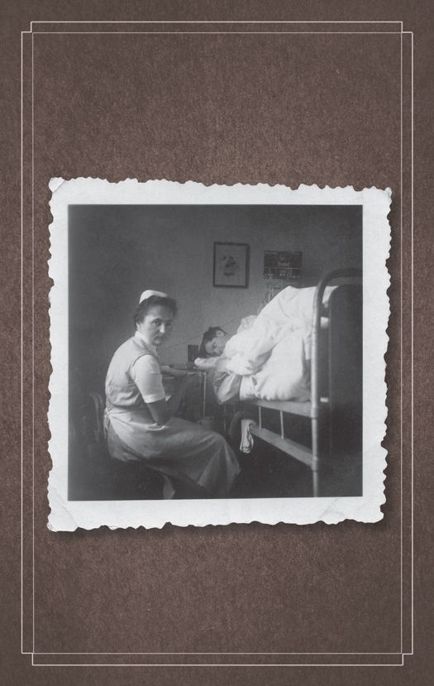

“How are they today?” the folding man asked the nurse.

“Getting worse,” she replied, buzzing from bed to bed. “I keep them sedated all the time now. Otherwise they just bawl.”

They had no obvious wounds. There were no bloody bandages, no limbs wrapped in casts, no bowls brimming with reddish liquid. The room looked more like overflow from a psychiatric ward than

a hospital.

“What’s the matter with them?” I asked. “They were hurt in the raid?”

“No, brought here by Miss Wren,” answered the nurse. “She found them abandoned inside a hospital, which the wights had converted into some sort of medical laboratory. These pitiful creatures were used as guinea pigs in their unspeakable experiments. What you see is the result.”

“We found their old records,” the clown said. “They were kidnapped years ago by the wights. Long assumed dead.”

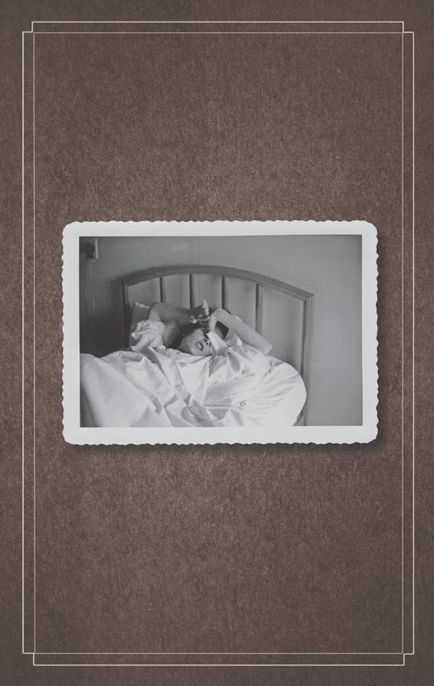

The nurse took a clipboard from the wall by the whispering man’s bed. “This fellow, Benteret, he’s supposed to be fluent in a hundred languages, but now he’ll only say one word—over and over again.”

I crept closer, watching his lips.

Call, call, call

, he was mouthing.

Call, call, call

.

Gibberish. His mind was gone.

“That one there,” the nurse said, pointing her clipboard at the moaning girl. “Her chart says she can fly, but I’ve never seen her so much as lift an inch out of that bed. As for the other one, she’s meant to be invisible. But she’s plain as day.”

“Were they tortured?” Emma asked.

“Obviously—they were tortured out of their minds!” said the clown. “Tortured until they forgot how to be peculiar!”

“You could torture me all day long,” said Millard. “I’d never forget how to be invisible.”

“Show them the scars,” said the clown to the nurse.

The nurse crossed to the motionless woman and pulled back her sheets. There were thin red scars across her stomach, along the side of her neck, and beneath her chin, each about the length of a cigarette.

“I’d hardly call this evidence of torture,” said Millard.

“Then what

would

you call it?” the nurse said angrily.

Ignoring her question, Millard said, “Are there more scars, or is this all she has?”

“Not by a long shot,” said the nurse, and she whisked the sheets off to expose the woman’s legs, pointing out scars on the back of the woman’s knee, her inner thigh, and the bottom of her foot.

Millard bent to examine the foot. “That’s odd placement, wouldn’t you say?”

“What are you getting at, Mill?” said Emma.

“Hush,” said Enoch. “Let him play Sherlock if he wants. I’m rather enjoying this.”

“Why don’t we cut

him

in ten places?” said the clown. “Then we’ll see if he thinks it’s torture!”

Millard crossed the room to the whispering man’s bed. “May I examine him?”

“I’m sure he won’t object,” said the nurse.

Millard lifted the man’s sheets from his legs. On the bottom of one of his bare feet was a scar identical to the motionless woman’s.

The nurse gestured toward the writhing woman. “She’s got one too, if that’s what you’re looking for.”

“Enough of this,” said the folding man. “If that is not torture, then what?”

“Exploration,” said Millard. “These incisions are precise and surgical. Not meant to inflict pain—probably done under anesthetic, even. The wights were

looking

for something.”

“And what was that?” Emma asked, though she seemed to dread the answer.

“There’s an old saying about a peculiar’s foot,” said Millard.

“Do any of you remember it?”

Horace recited it. “A peculiar’s sole is the door to his soul,” he said. “It’s just something they tell kids, though, to get them to wear shoes when they play outside.”

“Maybe it is and maybe it’s not,” said Millard.

“Don’t be ridiculous! You think they were looking for—”

“Their souls. And they found them.”

The clown laughed out loud. “What a pile of baloney. Just because they lost their abilities, you think their second souls were removed?”

“Partly. We know the wights have been interested in the second soul for years now.”

Then I remembered the conversation Millard and I had had on the train, and I said, “But you told me yourself that the peculiar soul is what allows us to enter loops. So if these people don’t have their souls, how are they

here

?”

“Well, they’re not

really

here, are they?” said Millard. “By which I mean, their

minds

are certainly elsewhere.”

“Now you’re grasping at straws,” said Emma. “I think you’ve taken this far enough, Millard.”

“Bear with me for just a moment longer,” Millard said. He was pacing now, getting excited. “I don’t suppose you heard about the time a normal actually

did

enter a loop?”

“No, because everyone knows that’s impossible,” said Enoch.

“It

nearly

is,” said Millard. “It isn’t easy and it isn’t pretty, but it has been done—once. An illegal experiment conducted by Miss Peregrine’s own brother, I believe, in the years before he went mad

and formed the splinter group that would become the wights.”

“Then why haven’t I ever heard about this?” said Enoch.

“Because it was extremely controversial and the results were immediately covered up, so no one would attempt to replicate them. In any event, it turns out that you

can

bring a normal into a loop, but they have to be

forced

through, and only someone with an ymbryne’s power can do it. But because normals do not have a second soul, they cannot handle a time loop’s inherent paradoxes, and their brains turn to mush. They become drooling, catatonic vegetables from the moment they enter. Not unlike these poor people before us.”

There was a moment of quiet while Millard’s words registered. Then Emma’s hands went to her mouth and she said quietly, “Oh, hell. He’s right.”

“Well, then,” said the clown. “In that case, things are even worse than we thought.”

I felt the air go out of the room.

“I’m not sure I follow,” said Horace.

“He said the monsters stole their souls!” Olive shouted, and then she ran crying to Bronwyn and buried her face in her coat.

“These peculiars didn’t

lose

their abilities,” said Millard. “They were stolen from them—extracted, along with their souls, which were then fed to hollowgast. This allowed the hollows to evolve sufficiently to enter loops, a development which enabled their recent assault on peculiardom—and netted the wights even more kidnapped peculiars whose souls they could extract, with which they evolved still more hollows, and so on, in a vicious cycle.”

“Then it isn’t just the ymbrynes they want,” said Emma. “It’s us, too—and our souls.”

Hugh stood at the foot of the whispering man’s bed, his last bee buzzing angrily around him. “All the peculiar children they kidnapped over the years …

this

is what they were doing to them? I figured they just became hollowgast food. But this … this is

leagues

more evil.”

“Who’s to say they don’t mean to extract the ymbrynes’ souls, too?” said Enoch.

That sent a special chill through us. The clown turned to Horace and said, “How’s your best-case scenario looking now, fella?”

“Don’t tease me,” Horace replied. “I bite.”

“Everyone out!” ordered the nurse. “Souls or no souls, these people are ill. This is no place to bicker.”

We filed sullenly into the hall.

“All right, you’ve given us the horror show,” Emma said to the clown and the folding man, “and we are duly horrified. Now tell us what you want.”

“Simple,” said the folding man. “We want you to stay and fight with us.”

“We just figured we’d show you how much it’s in your own best interest to do so,” said the clown. He clapped Millard on the back. “But your friend here did a better job of that than we ever could’ve.”

“Stay here and fight for what?” Enoch said. “The ymbrynes aren’t even in London—Miss Wren said as much.”

“Forget London! London’s finished!” the clown said. “The battle’s over here. We lost. As soon as Wren has saved every last peculiar she can from these ruined loops, we’ll posse up and travel—to other lands, other loops. There must be more survivors out there, peculiars like us, with the fight still burning in them.”

“We will build army,” said the folding man. “

Real

one.”

“As for finding out where the ymbrynes are,” said the clown, “no problem. We’ll catch a wight and torture it out of him. Make him show us on the Map of Days.”

“You have a Map of Days?” said Millard.

“We have two. The peculiar archives is downstairs, you know.”

“That is good news indeed,” Millard said, his voice charged with excitement.

“Catching a wight is easier said than done,” said Emma. “And

they lie, of course. Lying is what they do best.”

“Then we’ll catch two and compare their lies,” the clown said.

“They come sniffing around here pretty often, so next time we see one—bam! We’ll grab him.”

“There’s no need to wait,” said Enoch. “Didn’t Miss Wren say there are wights in this very building?”

“Sure,” said the clown, “but they’re frozen. Dead as doornails.”

“That doesn’t mean they can’t be interrogated,” Enoch said, a grin spreading across his face.

The clown turned to the folding man. “I’m really starting to like these weirdos.”

“Then you are with us?” said the folding man. “You stay and fight?”

“I didn’t say that,” said Emma. “Give us a minute to talk this over.”

“What is there to talk over?” said the clown.

“Of course, take all time you need,” said the folding man, and he pulled the clown down the hall with him. “Come, I will make coffee.”

“All

right

,” the clown said reluctantly.

We formed a huddle, just as we had so many times since our troubles began, only this time rather than shouting over one another, we spoke in orderly turns. The gravity of all this had put us in a solemn state of mind.

“I think we should fight,” said Hugh. “Now that we know what the wights are doing to us, I couldn’t live with myself if we just went back to the way things were, and tried to pretend none of this was happening. To fight is the only honorable thing.”

“There’s honor in survival, too,” said Millard. “Our kind survived the twentieth century by hiding, not fighting—so perhaps all we need is a better way to hide.”

Then Bronwyn turned to Emma and said, “I want to know

what

you

think.”

“Yeah, I want to know what Emma thinks,” said Olive.

“Me too,” said Enoch, which took me by surprise.

Emma drew a long breath, then said, “I feel terrible for the other ymbrynes. It’s a crime what’s happened to them, and the future of our kind may depend on their rescue. But when all is said and done, my allegiance doesn’t belong to those other ymbrynes, or to other peculiar children. It belongs to the woman to whom I owe my life—Miss Peregrine, and Miss Peregrine alone.” She paused and nodded—as if testing and confirming the soundness of her own words—then continued. “And when, bird willing, she becomes herself again, I’ll do whatever she needs me to do. If she says fight, I’ll fight. If she wants to hide us away in a loop somewhere, I’ll go along with that, too. Either way, my creed has never changed: Miss Peregrine knows best.”

The others considered this. Finally Millard said, “Very wisely put, Miss Bloom.”

“Miss Peregrine knows best!” cheered Olive.

“Miss Peregrine knows best!” echoed Hugh.

“I don’t care what Miss Peregrine says,” said Horace. “I’ll fight.”

Enoch choked back a laugh. “You?”

“Everyone thinks I’m a coward. This is my chance to prove them wrong.”

“Don’t throw your life away because of a few jokes made at your expense,” said Hugh. “Who gives a whit what anyone else thinks?”

“It isn’t just that,” said Horace. “Remember the vision I had back on Cairnholm? I caught a glimpse of where the ymbrynes are being kept. I couldn’t show you on a map, but I’m sure of this—I’ll know it when I see it.” He tapped his forehead with his index finger.