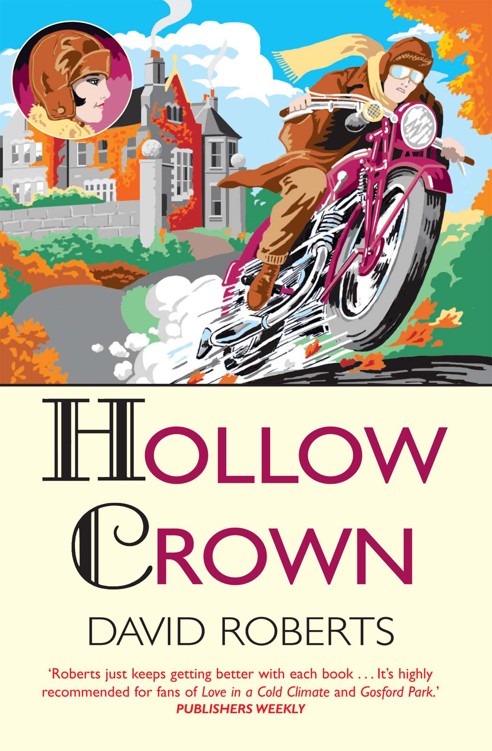

Hollow Crown

Authors: David Roberts

D

AVID

R

OBERTS

worked in publishing for over thirty years before devoting his energies to writing

full time. He is married and divides his time between London and Wiltshire.

Visit www.lordedwardcorinth.co.uk to find out more about David and the series.

Praise for David Roberts

‘A classic murder mystery with as complex a plot as one could hope for and a most engaging pair of amateur sleuths whom I look forward to encountering again in future

novels.’

Charles Osborne, author of

The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie

‘Roberts’ use of period detail . . . gives the tale terrific texture. I recommend this one heartily to history-mystery devotees.’

Booklist

‘

Dangerous Sea

is taken from more elegant times than ours, when women retained their mystery and even murder held a certain charm. The plot is both intricate and

enthralling, like Poirot on the high seas, and lovingly recorded by an author with a meticulous eye and a huge sense of fun.’

Michael Dobbs, author of

Winston’s War

and

Never Surrender

‘The plots are exciting and the central characters are engaging, they offer a fresh, a more accurate and a more telling picture of those less placid times.’

Sherlock

Titles in this series

(listed in order)

Sweet Poison

Bones of the Buried

Hollow Crown

Dangerous Sea

The More Deceived

A Grave Man

The Quality of Mercy

Something Wicked

For Penelope

and in memory of Geoffrey

Constable & Robinson Ltd

3 The Lanchesters

162 Fulham Palace Road

LondonW6 9ER

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2002

This paperback edition published by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2003

Copyright © David Roberts 2002

The right of David Roberts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form

of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-84119-774-6

eISBN 978-1-78033-421-9

Printed and bound in EU

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

For within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps death his court . . .

What must the king do now? Must he submit? The king shall do it: must he be depos’d? The king shall be contented: must he lose The name of king? O’ God’s name, let it go. Shakespeare, How now! a rat? Dead, for a ducat, dead! Shakespeare, |

October to December

1936

Almost against his will, Lord Edward Corinth gazed up at the sleek, glassy building he was about to enter. It brought to mind, as no doubt the architect intended, one of the

new ocean liners – the

Queen Mary

, say, or the

Normandie

– and it seemed to make every other building in Fleet Street appear dowdy and old-fashioned. It was the

headquarters of Joe Weaver’s

New Gazette

and it stood for everything he had achieved. Lord Weaver, as he now was, had come to England from Canada during the war. With skilful use of

his large fortune, he had made powerful friends in the world of politics and it is not too much to say that he was now in a position to make or break prime ministers. His great building, completed

in 1931, and in front of which Edward now stood, was brash, brutal and several storeys higher than any of its neighbours.

After dark – it was now nine o’clock – from where he was standing, it looked like a shining curtain, each pane of glass illuminated brilliantly from within. One might be

forgiven, he thought wryly, for imagining that its transparency was a symbol of the veracity with which the

New Gazette

reported the news in its august columns, but, as he was well aware,

for Lord Weaver truth was what he wanted it to be. The press lord, for all his bonhomie, was a man of secrets. If he wished to spare one of his friends or dependants the pain of reading in his

newspaper the sordid details of their divorce proceedings, he would order his editor to deny his readers the pleasure of

schadenfreude

. If he wished to puff the prospects of some bright

young man he had taken under his wing, he would paint such a portrait that even the man himself might have difficulty recognizing. For every favour there was, of course, a price to be paid. No

money would change hands – Lord Weaver had money to spare – but from the men he would elicit information and through them exercise influence. The women were also a source of information

and their influence extended beyond their husbands to their friends and lovers – and it was said that, despite having a face like a wicked monkey, Weaver was himself to be found amongst the

latter category more often than a casual observer would have thought likely.

And yet Lord Weaver was by no means a bad man. He loved his wife, considered himself a patriot and used what power he had in what he considered to be the best interests of his adopted country.

He was a loyal friend, as Edward had reason to know, and he was generous – when the whim took him – absurdly, extravagantly, generous. But still, Edward bore in mind that, even when the

tiger smiled, he was still a tiger.

As he stepped into the entrance hall Edward again hesitated. Its art deco opulence was almost oppressive. The designer – a man called Robert Atkinson – had intended to overwhelm the

visitor with the power and energy of the

New Gazette

and its proprietor, and he had succeeded. It was no mere newspaper, Atkinson seemed to be saying, but a Great Enterprise, a Modern

Miracle, a temple to the

Zeitgeist

. The floor was of inky marble veined with red and blue waves of colour which glowed and shimmered in the light of a huge chandelier. The ceiling was silver

leaf, fan vaulted to summon up an image of the heavens, but the massive clock above the marble staircase reminded the visitor that time was money. Two shining bronze snakes, acting as banisters,

hinted that there might be evil even in this paradise and Edward wondered if it really could be the designer’s sly joke. Weaver was clever enough not to have any statue or bust of himself in

the entrance hall. No doubt after he was dead, that omission would be rectified, but for now he was content to

be

the newspaper.

Edward went over to a horseshoe desk – rosewood and silver gilt – and was greeted respectfully by a liveried flunkey and taken over to the gilded cage which would raise him by magic

to the great man’s private floor on the top of the building. Edward smiled to himself – it really was too much. The porters’ frog-footman uniforms were certainly a mistake. He

greeted by name the wizened little man who operated the lift. He at least was real – an old soldier who had lost an arm on the Somme. He seemed to read Edward’s thoughts for he winked

at him as if they shared a private joke before whisking him heavenward.

Edward was in a foul mood. He had dined at his club and had by chance overheard some remarks which, because they were so apt, hurt him to the core. He had finished his cigar in the smoking room

and was making his way towards the door when he saw the candidates’ book on a desk behind a screen and remembered he had promised to add his signature in support of a friend’s son who

was up for election. As he turned over the pages, he heard the voice of the man with whom he had been chatting a few moments before. He must have believed Edward had left the smoking room and not

realized he was still in earshot.

‘Do you know that fellow?’ the man was saying. ‘We were at Cambridge together – a typical victim of the System. At Cambridge he was considered the cleverest of us all. He

had brains, romantic looks, £12,000 a year. A duke’s son with every advantage – we thought he would go far. But what has he done or accomplished? Nothing except to be bored and

miserable.’

Edward, not waiting to hear the response, slipped out of the room, his face burning. This was what men thought of him, damn it! And what was worse, this was what he thought of himself. It was

true he had told no one of his adventures in Spain a few months previously when he had uncovered the identity of a spy and a murderer, but what did that amount to in the scheme of things? He wanted

a job and that was why he had decided he might as well go and see what Lord Weaver had to say. He was damned if he was going to hang about London going to dinners and balls, and make small talk

with girls in search of a husband and their monstrous mothers. For one thing, he was too old for that – he was thirty-six. The world was going to the devil and he wanted to play some part in

preparing Britain for the war which he now believed was inevitable. But how? What part? He was too old for the army. He had offered his services to the Foreign Office and been rejected. Was it

possible Joe Weaver could help him? He would soon know.

‘May 12

th

, isn’t it?’

‘The coronation? Yes – that is, if it ever happens.’ Weaver had almost entirely lost his Canadian accent, Edward noted, and affected a bear-like growl.

‘What on earth do you mean, Joe?’ Edward, his cigarette lighter in his hand, paused and looked at Weaver in surprise.

‘You remember what they were saying about Mrs Simpson when you were in New York . . . she’s not pure as the driven snow, you know. For one thing she’s still got a

husband.’

‘I see but . . . ’ Edward hesitated. He didn’t like to speak ill of his king. ‘. . . does he really intend to marry the woman? I mean, he’s had these . . .

infatuations before.’

‘This is different, Edward, I can assure you. I’ve seen it with my own eyes.’

‘Of course, that’s the set you move in. Didn’t I hear you had them on your yacht?’

‘Yes, a cruise along the Dalmatian coast. You should have come with us.’