Holmes and Watson (12 page)

Authors: June Thomson

Unfortunately, for it is one of the most important cases of this period, Watson decided not to publish a full account of the case on the grounds that the events were too recent and the subject-matter too concerned with politics and finance for what he modestly refers to as his ‘series of sketches’. One suspects, however, that there were more powerful reasons behind his decision. Pressure may even have been brought on Watson by highly-placed government officials to prevent him from publishing the full facts.

The strain of the Maupertuis inquiry, which lasted for two

months and kept Holmes working fifteen hours a day, at times for five days at a stretch, without proper rest, brought about a complete breakdown in his health. On 14th April 1887, despite his iron constitution, he was taken ill in France while staying at the Hotel Dulong in Lyons, where presumably he was still engaged in completing his enquiries into the Maupertuis case. Watson, summoned by telegram, hastened to his side and found Holmes in a state of nervous prostration, suffering from deep depression in a room which was, ironically, ankle-deep in congratulatory telegrams.

Watson immediately took charge, escorting Holmes back to Baker Street. A week later, Watson accompanied him to Reigate in Surrey to stay with his old army friend from his Afghanistan days, Colonel Hayter, for a period of convalescence. However, despite Watson’s best efforts to persuade him to rest, Holmes immediately became involved in the Reigate Squire inquiry, a case which he was successfully to solve.

Work was always for him a necessity. It was idleness he could not tolerate. ‘My mind rebels at stagnation,’ he tells Watson, and Watson himself remarks that Holmes’ ‘razor brain blunted and rusted with inaction’.

The latter years of this period (1881–9) were particularly significant for both of them, marking Watson’s first success as an author and bringing Holmes into contact with an arch criminal of such superior intellectual powers that he was to prove not only an adversary worthy of the name but almost a match for Holmes’ own remarkable intelligence and investigative skills.

*

See Appendix One for the dating of this case.

*

This account is published in the States under the title ‘The Adventure of the Reigate Squires’.

*

This case, which is deliberately undated by Watson, is assigned by some commentators to this 1881–9 period. However, in agreement with other Sherlockian scholars, I have placed it in the later period (1894–1903), after Watson’s return to Baker Street.

*

Holmes may be referring to King Oscar II (1829–1907), who ruled Sweden and Norway from 1872 until 1905, when Norway gained its independence. The King of Bohemia was engaged to one of the daughters of the King of Scandinavia (see Chapter Nine).

†

The case involving Wilson, the manager of a district messenger office, whose good name Holmes saved and possibly also Wilson’s life, may belong to this period or to the time when Holmes was practising at Montague Street. One of Wilson’s messenger boys, who had helped with that inquiry, also assisted Holmes in the Hound of the Baskerville case.

*

Although Holmes was not aware of it, he was also incorrect in assuming that the swamp adder in the Speckled Band inquiry was summoned by its owner’s whistle. All snakes are deaf, a fact of which Holmes was apparently ignorant. Presumably the snake was tempted back to Roylott’s room by the scent of the saucer of milk he put out for it.

FRIEND AND FOE

1881–1889

‘When you have one of the first brains of Europe up against you and all the powers of darkness at his back, there are infinite possibilities.’

Holmes on Moriarty:

The Valley of Fear

In 1887, the same year in which Holmes won European fame with his investigation of Baron Maupertuis and the Netherland-Sumatra Company, Watson achieved his own success with the publication in Beeton’s Christmas Annual of

A Study in Scarlet

, the first case on which he accompanied Holmes in March 1881, shortly after their meeting.

*

With his usual modesty, Watson himself makes no reference to this minor triumph, although he must have been delighted when, in the course of the Baskerville inquiry in October 1888, Jack Stapleton, one of Sir Henry’s neighbours, told him that both the names Holmes and Watson were already familiar to him through Watson’s ‘records’. By this, he must mean

A Study in Scarlet

, the only one of Watson’s accounts which had been published at that date.

It had taken Watson nearly six years for this account to appear in print and for him to fulfil his promise to Holmes to make his name better known; rather late, for, by the time it was published, Holmes’ reputation was already established on both sides of the Channel. The fee Watson received must have gone a little way towards helping with his finances, although he remained short of money. In August 1888, the possible date of the Cardboard Box case and a particularly hot summer when he was hoping to escape to the New Forest or to the coast at Southsea, he was forced to postpone his holiday and remain in London due to lack of funds.

It would seem that Watson had written up accounts of other cases during this period. In ‘The Adventure of the Copper Beeches’, which according to the chronology given in Chapter Six is dated 1885, Holmes speaks of ‘records of our cases which you have been good enough to draw up’. But as not even

A Study in Scarlet

had appeared in print at that time, Holmes had presumably read these accounts in manuscript form only. Like many

other aspiring authors, Watson evidently had problems in finding a publisher willing to take his work, almost certainly a keen disappointment to him, although with characteristic self-effacement he never mentions it.

The reference in ‘The Adventure of the Cardboard Box’ to Watson’s account of the Sign of Four case is surely another example of Watson’s carelessness over facts, a point which has already been examined in Appendix One under the notes on Chapter Six for the dating of this particular account.

Holmes’ attitude to Watson as his chronicler is ambivalent. On the one hand, he praises him for choosing those cases which, though trivial in themselves, best illustrate his own skills at ‘logical synthesis’ rather than concentrating on the

causes célèbres

. However, he criticises Watson over his style and for putting too much ‘life and colour’ into his accounts to the detriment of that ‘severe reasoning from cause to effect’ which Holmes considered the most important feature of his investigations. As he remarks, ‘Crime is common. Logic is rare.’

No budding writer likes to have his work disparaged and, quite naturally, Watson was annoyed by Holmes’ attitude, seeing it as an example of his egotism, although the reproof was not entirely unjust. As an author, Watson has on occasions a tendency towards exaggeration which is seen, for example, in his description of Alexander Holder (‘The Adventure of the Beryl Coronet’). It is difficult to believe that the senior partner in the second largest City of London bank would behave quite as hysterically as

in Watson’s description of him plucking at his hair and banging his head against the wall. Holmes was not the only one with a leaning towards the dramatic.

However, when Holmes himself later turned author and wrote up an account of his own, ‘The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier’, he was to admit it was not easy to keep rigidly to facts and figures if the material was to interest the reader. When he came to write his second account, ‘The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane’, a case which occurred after his retirement from active practice, his style contains as much ‘life and colour’ in the way of description as any of Watson’s narratives.

Holmes’ brother, Mycroft, showed more sensitivity on the subject of Watson’s authorship when he was introduced to him at the beginning of the Greek Interpreter case. ‘I am glad to meet you, sir,’ he says to Watson. ‘I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.’ It is an obvious reference to the publication several months earlier of

A Study in Scarlet

and was intended to flatter for, by this time, Holmes’ name was already well known. Like his brother, Mycroft could show considerable social charm when the occasion demanded it.

Because of this reference, the Greek Interpreter case is usually assigned to the summer of 1888, although some commentators have preferred to date it much earlier on the grounds that Holmes would not have waited for over six years before even mentioning to Watson that he had a brother, let alone introducing him to Mycroft. However, the time gap is perfectly understandable. As Watson

explains in the opening paragraph of ‘The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter’, Holmes was extremely reticent both about his relations and his early life, an attitude Watson interpreted as an indication of Holmes’ lack of emotion. This is certainly part of the explanation. But, as we have seen in Chapter One, Holmes’ unhappy childhood could well have caused him deliberately to avoid discussing that period in his life as too painful a subject.

It was an experience which had affected Mycroft as well. Like Holmes, he was a bachelor without friends, and was even more unsociable than his brother, his life being restricted to his Whitehall office, his lodgings in Pall Mall and the Diogenes Club

*

opposite his rooms, of which he was a founder-member and where he could be found every evening from a quarter to five until twenty to eight. As Holmes says of him, ‘Mycroft has his rails and he runs on them.’ For him to break his routine and actually visit Baker Street would be as extraordinary as seeing a tram coming down a country lane.

Holmes was evidently in close contact with his brother as he speaks of consulting him ‘again and again’ over difficult cases. Indeed, Mycroft had expected Holmes to ask for his advice over the Manor House affair shortly before introducing him to Watson. Presumably the two brothers met either at Mycroft’s bachelor apartment or

at the Diogenes Club in the Strangers’ Room, the only part of the premises where conversation was permitted. He never apparently visited Holmes in Baker Street, for when he called there during the Greek Interpreter inquiry his presence was so unexpected that Holmes gave a start of astonishment on seeing him. Under such circumstances, it is hardly surprising that Watson had not met him before 1888.

There was no filial jealousy between the two brothers. In fact, Holmes openly acknowledged Mycroft’s superior powers of observation and deduction. But, through lack of ambition and energy as well as an inability to work out the legal practicalities of bringing a case to court, Mycroft preferred to conduct his detection from the comfort of his armchair. If it meant exerting himself, he would rather his deductions were considered wrong than go to the trouble of proving them right.

Much to Watson’s amusement, he was treated to a demonstration of Mycroft’s superior powers of observation when the latter corrected his brother over the matter of the number of children a passer-by in the street possessed from the toys the man carried under his arm. It was clearly a game the brothers had played before, perhaps even in boyhood, and indicates a close and warm relationship. Holmes’ manner of addressing his brother as ‘my dear Mycroft’ suggests affection, while Mycroft’s use of the term ‘my dear boy’ has an almost paternal ring about it, an aspect of their relationship which has already been examined in Chapter One.

Ostensibly Mycroft, who had, as Holmes describes it, ‘an extraordinary faculty for figures’,

*

was employed as an auditor in some of the Government departments for a salary of £450. It was only eight years later, in November 1895 during the case of the Bruce-Partington plans, that Holmes confided in Watson Mycroft’s true role. With his unique capacity for remembering and correlating facts, Mycroft acted as a confidential adviser to various Government ministers on which policies they should pursue. As such, Mycroft was the most indispensable man in the whole country and at times

was

the British Government, as Holmes rather dramatically expresses it. ‘The conclusions of every department are passed to him,’ Holmes explains to Watson, ‘and he is the central exchange, the clearing-house, which makes out the balance. All other men are specialists, but his specialism is omniscience.’

Some commentators have regarded this long silence on Holmes’ part about his brother’s true role as curious, given the close friendship between Holmes and Watson. But as it was a highly confidential Governmental matter, Holmes may not have been in the position to divulge it even to Watson until he had received permission to do so from Mycroft.

Physically, the brothers were not alike. While Sherlock

was thin, Mycroft, although tall, was stout to the point of corpulence and gave the impression of ‘uncouth physical inertia’, in contrast to Sherlock’s quick and energetic manner. But despite his unwieldy frame, Mycroft’s head, with its ‘masterful brow, alert deep-set eyes, steel grey in colour, and firm lips’, was so strongly suggestive of his dominant mind that one quickly forgot his ‘gross body’. It was only in the sharpness of his expression that Watson could see any family resemblance, and Mycroft’s eyes had on occasions the same ‘far-away, introspective look’ of Sherlock’s when he was brooding over some particularly difficult case.

It was during this same period, 1881–9, that one other important encounter was made, two if the Charles Augustus Milverton inquiry is included, although commentators disagree over its date. However, for reasons explained in Appendix One, I am more inclined to assign this case to the later period, 1894–1902, and this investigation will therefore be more fully discussed in Chapter Fourteen.

But there is no doubt at all that at some time between 1881 and 1889, almost certainly towards the latter end of the period, Holmes came into contact with someone who was to play a significant role in his future; Watson’s, too, although it was Holmes who was the more deeply affected. This man was Professor James Moriarty, whom Holmes was subsequently to refer to as the ‘Napoleon of crime’.

It is not known precisely when Holmes first heard of him, nor did he actually meet him face to face until several

years later. But by January 1888, the date usually ascribed to the Valley of Fear case, Holmes had already accumulated a comprehensive dossier on Moriarty’s background and activities. According to his researches, Moriarty came from a good family and had enjoyed the benefits of an excellent education but had inherited criminal tendencies, thus bearing out Holmes’ theory about the importance of heredity and how certain aptitudes and characteristics can be passed on to subsequent generations through the blood line.

Little else is known about Moriarty’s background, except for the fact that he was a bachelor and had two brothers. The younger one was a station-master in the West of England and was presumably respectable. Another, an army Colonel, was also called James, a duplication which has led some commentators to assume that James Moriarty was a double-barrelled surname. The family may have been of Irish descent, as other Sherlockian scholars have suggested, although this is not known for certain. Neither is his date of birth. While he is clearly older than Holmes, any theories which give the year he was born, and they vary from 1844 to as early as 1830, are speculative.

What is quite evident, however, is Moriarty’s remarkable intelligence. Holmes, even when acknowledging the man’s genius for evil, openly admits his admiration for the Professor’s ‘extraordinary mental powers’ and ‘phenomenal mathematical faculty’.

‘My horror at his crimes,’ he was later to confess to Watson, ‘was lost in my admiration for his skill.’

At the age of twenty-one, Moriarty had written a treatise on the binomial theorem, as a result of which he was offered the Chair of Mathematics at ‘one of our smaller universities’, a post he was still holding when Holmes first came to hear of him. Although Holmes does not specify which university this was, Philip A. Shreffler may well be correct in suggesting it was Durham, a theory he put forward in an article, ‘Moriarty: A Life Study’, published in the

Baker Street Journal

in June 1973. According to this theory, Holmes cannot be referring to either Oxford, Cambridge or London as none of these can be described as ‘one of our smaller universities’, while the pronoun ‘our’ suggests an establishment in England rather than Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. As the only English provincial university at the time was Durham, it must have been there that Moriarty held the Chair of Mathematics, although there is no record of his having served in this post.

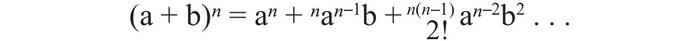

The problem of raising a binomial, that is two terms connected by a plus or minus sign, to the

n

th power, had taxed mathematicians for many years. Although simple cases such as (a + b)

2

= a

2

+ 2ab + b

2

could be easily worked out, high powers proved difficult and fractional powers impossible. In 1655, Sir Isaac Newton had devised the binomial theorem: