Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II (21 page)

Read Horror in the East: Japan and the Atrocities of World War II Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

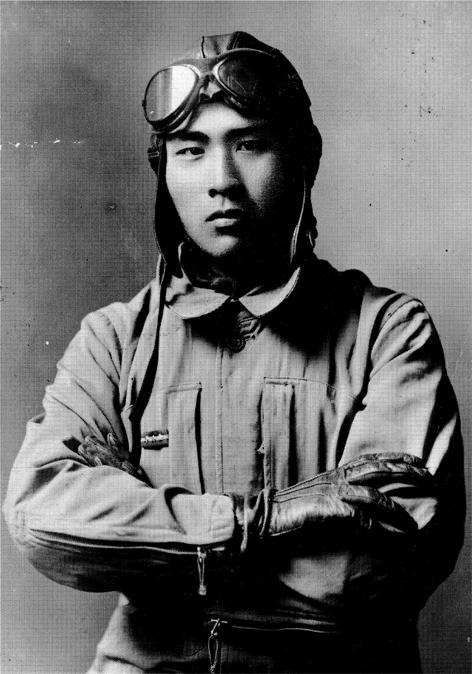

In 1943 Oonuki joined the imperial armed forces and underwent pilot training: ‘The young people at that time had a sense of longing about being a pilot,’ he says.

‘I thought being a pilot may be interesting — so it was a simple motivation.

Nobody dreamt that this kind of sad ending was awaiting.’

Shortly after the first kamikaze attacks off the Philippines in October 1944, all the pilots at Oonuki’s training base were called to a meeting.

A senior officer told them that recruitment was currently taking place for a ‘special mission’, and that if they volunteered they should be clear that there was no possibility of surviving it.

The pilots were told that they should think over whether they wished to volunteer for the mission or not, and the next morning each should answer in one of three ways: ‘No’, ‘Yes’ or ‘Yes, I volunteer with all my heart.’

That night the pilots discussed amongst themselves what they should do.

One of them, on behalf of the whole group, went and asked the senior officer to describe this ‘special mission’ in more detail.

He was told that all the pilots who volunteered would be asked to crash their planes into enemy warships.

Again, it was emphasized that survival was impossible.

‘We were taken aback,’ says Oonuki.

‘I felt it was not the type of mission I would willingly apply for.’

He was happy to face the possibility — even the probability — of death as a pilot, but this ‘certain death’ seemed ‘ridiculous’.

All the other pilots agreed with him and ‘nobody was really willing to go’.

But then they started working through the consequences of refusing to ‘volunteer’.

They thought it certain they would be accused of cowardice and subjected to that most terrifying of punishments for a Japanese — shame and ostracism from the group.

Then this verdict would be reported to their families, and they too would be punished with ostracism, condemned to be shunned by all other Japanese.

‘I’ve heard of many cases such as this in the past,’ says Oonuki.

It was a fate that none of them wished to bring on the families they loved.

Then, as they sat talking through the night, another likely consequence of refusing to volunteer occurred to them.

Those who did not become kamikazes would most likely be ‘isolated and then sent to the forefront of the most severe battle and meet a sure death anyway’.

As a result of this careful, logical thought process, next morning every pilot volunteered to become a kamikaze, all signing that they freely put themselves forward ‘with all their heart’.

‘Nobody wanted to,’ says Oonuki, ‘but everybody did.’

Kenichiro Oonuki’s testimony offers a hugely revealing insight into the mentality not just of the kamikazes, but of many Japanese during the war.

His frank comments render inadequate the Westernized notion of the mindless fanaticism of the Japanese, and explode the idea that the Japanese are somehow ‘inscrutable’ or devoid of feelings with which Westerners can readily empathize.

The dilemma that Oonuki and his comrades faced that night, as they sat and decided whether they should ‘volunteer’, is readily understandable to everyone who hears it — as is their subsequent decision to become kamikazes.

In fact, given the circumstances, the exceptional person would have been the one who did not volunteer.

An idea of how these rare individuals who stood out against the group were perceived by those in authority is given by Tadashi Nakajima, a commander in the Imperial Navy who was involved, as he puts it, in ‘kamikaze administration’.

‘One lieutenant didn’t want to become a kamikaze pilot,’ he says.

‘He came over and told me so.

And as a result he was going to be transferred.

Then the American enemy came, all of a sudden, so we all ran.

After the enemy planes had gone we reassembled for a head-count.

There was one person missing — and it was this lieutenant.

He had been shot through the neck and killed.

Every single other person was alive except this man who had gone to ask for a transfer.

It’s very strange, isn’t it?’

The unfortunate lieutenant who did not volunteer to be a kamikaze was dead within minutes — but how much longer would he have lasted even if the Americans had not appeared?

He was almost certainly going to be ‘transferred’ to a frontline squadron where he would have had little hope of survival.

Kenichiro Oonuki and his comrades were surely right — not to volunteer could still be a route to death.

Tadashi Nakajima says he felt little pity for the young pilots whom he sent on suicide missions: ‘I’ve studied Zen a little bit, and in Zen life and death do not exist.

And so just because a person dies a little before you, the difference is really unimportant if you think of life and death on a Zen timescale — the timescale of the universe.’

The fact that ‘on the timescale of the universe’ it was not important that they were all to die young was not much comfort to Kenichiro Oonuki and his comrades as they embarked on a conversion course to turn them from conventional pilots into kamikazes.

They spent some weeks training in ‘rapid descent towards the ground’ and ‘nose diving’.

Practising to crash was extremely dangerous, because if they ‘made a little mistake there’s no possibility of correcting the altitude of the plane.

I saw many die during the training.

And if you hit the ground,’ says Oonuki, ‘it’s very difficult to collect up the pieces of the bodies.’

In the spring of 1945 they were told their training was over and they were to take part in the kamikaze attack on the Allied fleet off Okinawa.

By now Oonuki was at peace with himself: ‘When you come to the last stage you have a sense of resignation.’

The night before his squadron of a dozen kamikazes was due to depart ‘there was a lot of sake, but nobody could feel cheerful — we went to bed at about nine.’

The next morning he went to check his aircraft and was told that because of mechanical problems his plane could not fly — indeed, only half of the squadron, six planes, were in a fit state to leave at the appointed time of 3.30 in the afternoon.

Oonuki was disappointed — he wanted to die not alongside strangers but alongside the comrades with whom he had trained.

That afternoon, as six of his colleagues prepared to leave he went up to them as their engines were running and gave them each a bouquet of azaleas.

‘And one comrade said, “I am going ahead of you.

I wanted to meet my destiny with you — I’m sorry.”

Everybody had the same expression in their eyes, like a deep-sea fish looking up at the blue sky above.

I’ve never seen sadder expressions in anyone’s eyes since then.’

Two days later, on 5 April 1945, it was finally Kenichiro Oonuki’s turn to leave.

His plane repaired, he flew off with another kamikaze squadron towards Okinawa.

But

en route

his plane developed engine problems and he had to land on a Japanese-occupied island and effect repairs.

The next day he and three other kamikazes flew on again, but twenty minutes’ flying time from Okinawa they were attacked by American fighters and the other kamikazes were shot down.

‘Right in front of me my colleagues died,’ he says.

‘When they fall it’s almost like a little chunk of stone.

The Americans kept on attacking and I made a rapid turn and tried to escape and then my plane was hit.

It was a tremendous shock — almost like you’re beaten by a fist.’

His plane was losing oil rapidly from a lubricant tank, but by a great piece of good fortune he was able to make an emergency landing on one of the smaller Ryukyu islands.

‘It was a miraculous landing,’ he says.

‘There were potholes all over the runway — and if I’d hit a pothole the plane would have toppled over and I would have died.’

Left on the island with a disabled plane he felt a ‘sense of dishonour’ that he had not been able to complete his suicide mission.

After ten days a Japanese ship arrived at the island and Oonuki began a tortuous journey back to the home islands of Japan.

Once back at base he and a selection of other kamikaze pilots who had failed in their mission were berated: ‘The commanding officer and the general staff officer came out, and the first thing they said was, “Why did you come back?”

We thought that they would say, “You’ve had a tough time.

Have a rest and we’ll give you another plane to join a new kamikaze mission.”

But we were all reprimanded, scolded.’

Oonuki and his comrades were confined to quarters and brutally treated: ‘I was beaten with a bamboo sword and for two days I was in bed — I couldn’t move at all.

And many others had to go through that.

Some broke the glass window and tried to kill themselves, but we saved them.’

At the end of the war Oonuki and the rest of the failed kamikaze pilots were released from the isolation of their imprisonment, but he did not talk about his experience until relatively recently: ‘We who survived felt a deep sense of guilt.

Your colleagues with whom you felt a stronger bond almost than with your own family had died, and you had simply survived.

In captivity it was a very painful experience, with the mental torture of being called disloyal and a coward, and if we had disclosed what had happened that would have been another dishonour to us.’

Now, looking back on all his experiences as a kamikaze, Oonuki has formed a straightforward view about the worth of these ‘special attack missions’: ‘It was folly, reckless.

It was simply ridiculous.’

Those who watched the propaganda newsreels were invited to form a very different opinion.

One typical film shows kamikaze pilots waiting to be sent on a mission being read a special message from Hirohito: ‘These words are from the Emperor,’ they are told.

‘Those who attacked the enemy individually have done a great job and produced remarkable results.

How brave they were to sacrifice their lives for their country.’

Their commanding officer then goes on to say that ‘the Emperor has ordered us to pass his sincere sympathies to the late families of the deceased and to their colleagues on the front line.’

After this message one of the kamikaze pilots on parade salutes and says: ‘I would like to thank the Emperor on behalf of us all.

We are so proud and impressed that the Emperor himself sent us such words.

We promise to accomplish our mission as bravely as our predecessors.’

The effect of such propaganda was profound.

The central message — that the divine emperor himself was wholly in favour of suicide attacks — was simple and had an inescapable impact.

‘I thought they [the kamikazes] were doing very well,’ says Shigeaki Kinjou, who was in his teens at the time.

‘I believed that they were sacrificing their lives for the country.

And civilians, we should also be ready to sacrifice our lives for the country when the time came.’

Kinjou lived on the small island of Tokashiki, a few miles from Okinawa.

In March 194S, the Americans landed on Tokashiki and started to move inland.

Immediately the Japanese army issued hand grenades to some of the villagers.

Significantly they gave out two to each person — one to throw at the Americans and the other to blow themselves up.

Just as at Saipan, the army told the islanders that they would be tortured, raped or murdered by the Americans if they were captured.

It was also made clear to the civilians that it would be shameful to surrender.

The role of the army in provoking the tragedy that subsequently occurred is hard to underestimate — as on Saipan, the soldiers knew that they were forbidden to surrender and must have felt desperately concerned for the welfare of any civilians left behind (and perhaps, if one was to view the situation cynically — a little resentful that other Japanese in the vicinity would survive them).

Above

Kenichiro Oonuki in a defiant pose, symbolic of the propaganda image of the Kamikaze pilot.

But belying the popular myth of willing self-sacrifice, Oonuki and his comrades volunteered knowing that the idea of dying in a suicide attack was ‘ridiculous’